(Paying Subscribers, at the bottom is a rare print interview with trombonist Tom Brown.)

(For the previous essays in this series, see the Index.)

So, as we read last time, “Scoop” Gleeson does appear to have been the only one to use “jazz” in print between March 3rd and 24th, 1913. But this distinction only lasted for those few weeks. Other writers soon joined in, beginning with his colleague Francis J. Mannix on March 25 in the S.F. Bulletin, p.16. On April 10, the Vallejo Evening Chronicle (p.3), located about a 40-minute drive south of Boyes, toward S.F., reported that a baseball player did not “possess enough ‘jazz’ to keep his job.” The next day, the same paper (p.5) talked about a manager who “never saw a bunch of youngsters with so much ‘jazz’.” In this newspaper none of the authors are listed, but the style is clearly not Gleeson’s peppy, slangy approach. The word “jazz” returns in this paper on April 12, 14, 19, 23, May 2, and so on all the way into December and through the next years. (In the digital archives this paper is sometimes listed as The Solano Napa News Chronicle, but that was its name many years later, not at this time.) On the other hand, William “Spike” Slattery, who introduced the word to Gleeson, rarely used it in print—the first time was in September 1913.

Soon it spread beyond baseball columns. Frances Jolliffe (1873-1925), a prominent suffragist activist, was also an arts critic. On May 26, 1913, in a review of the comedy “Hanky Panky,” produced by the legendary Lew Fields and then playing at a theater in San Francisco, she wrote approvingly:

The expression that she begins with is an old way of giving emphasis—similar to, “She puts the ‘you’ in ‘youth.’” It’s a way of saying “They practically invented jazz!”

And the word "jazz" started appearing in print outside of California. For example, the Daily Republican (Rushville, Indiana), June 7, 1913 had an article that said “It means anything you may happen to want it to." This was found by Dave Wilton, along with the similar article from Duluth, Minnesota, June 22, 1913, that we saw in Part 3. Later that month, when “Hanky Panky” came to Canada, the Winnipeg Tribune, June 28, 1913, page 18, re-published most of Jolliffe’s review (thanks to Robert Loerzel for that). So the word was now known in Canada.

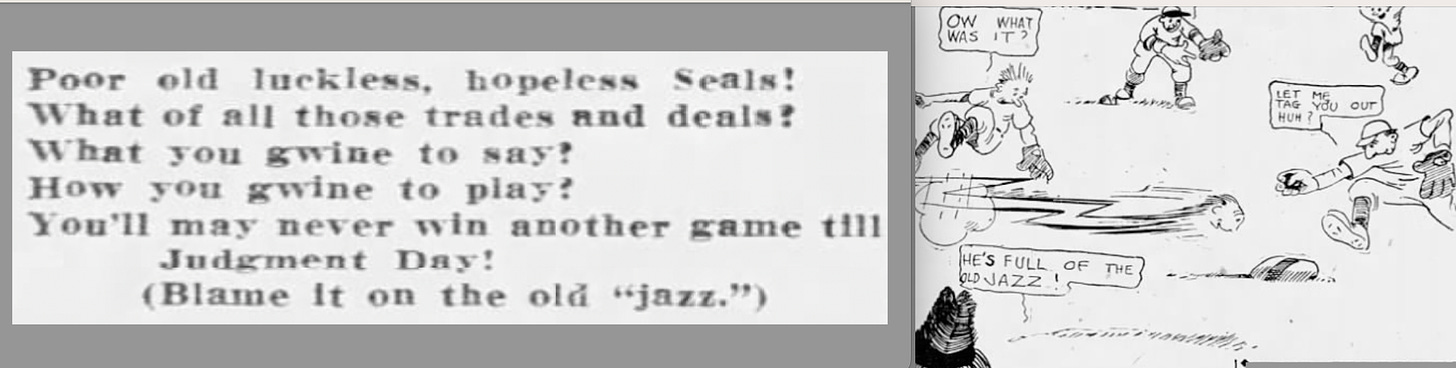

In fact, the word was already becoming so widely used, and in so many different contexts, that sometimes it’s hard to tell whether it’s being used in a positive or negative sense (as in “Don’t give me that jazz!’,” discussed in Essay 2). For example, here on April 10, 1913, p.14 of the Bulletin, Gleeson begins a long article with a cute poem about the San Francisco Seals, a minor league baseball team, that concludes “Blame it on the old ‘jazz.’” This appears, at a glance, to mean “jazz” in the negative sense of too wild and undisciplined. But elsewhere on this page, a cartoonist, Breton, uses it in a clearly positive sense, showing how the old “jazz” makes a player run so quickly that he can’t be tagged out! I put the two items right next to each other below—originally they appeared on the same page, but separated by a few columns:

These two excerpts appear to have opposing meanings. But, since Gleeson was a big promoter of “jazz,” it’s hard to believe that he would mean that “jazz” would make the players perform badly. I asked several people for their “take” on the meaning of the poem. It was my older brother Spence who figured it out: If one reads the full article that follows the poem, it’s clear that Gleeson is lamenting that the team’s leadership has made some bad choices that has left them with the weakest lineup in their league. (It was early in the season, and they had already lost six out of eight games.) And notice that the last line is in parentheses, meaning that it’s addressed to the reader. So, the poem means:

You Seals have made some bad trades and deals.

You might never win another game with such a weak team as this.

(Reader, if it makes you feel any better, blame it on “jazz,” but that’s not my opinion—you’re only kidding yourself.)

(“You’ll” in the 5th line is a typo for “you,” and “gwine” is an approximation of a Southern U.S.A. accent for “going,” and not specifically meant to sound Black, as some people think.)

However, it’s still not clear exactly how Gleeson intends us to take the word “jazz.” Does he mean, “You can go ahead and blame it on them for not having enough “jazz,” that is, energy, or does he mean “Blame it on them for having too much “jazz,” that is, too much wild and undisciplined energy and over-confidence? I lean toward the last meaning, but we can’t definitely resolve this.

So the word “jazz” was spreading, and being used in a variety of contexts. Now, we learned last time that Chicago White Sox baseball players visited Boyes Springs in March 1913, and were, according to the newspaper, introduced to the “old ‘jazz.’” Clearly, they learned the word there, and it’s safe to assume that the individual athletes used it now and then when they were back in Chicago. But how—and when— did the word become the name of the music we all love?

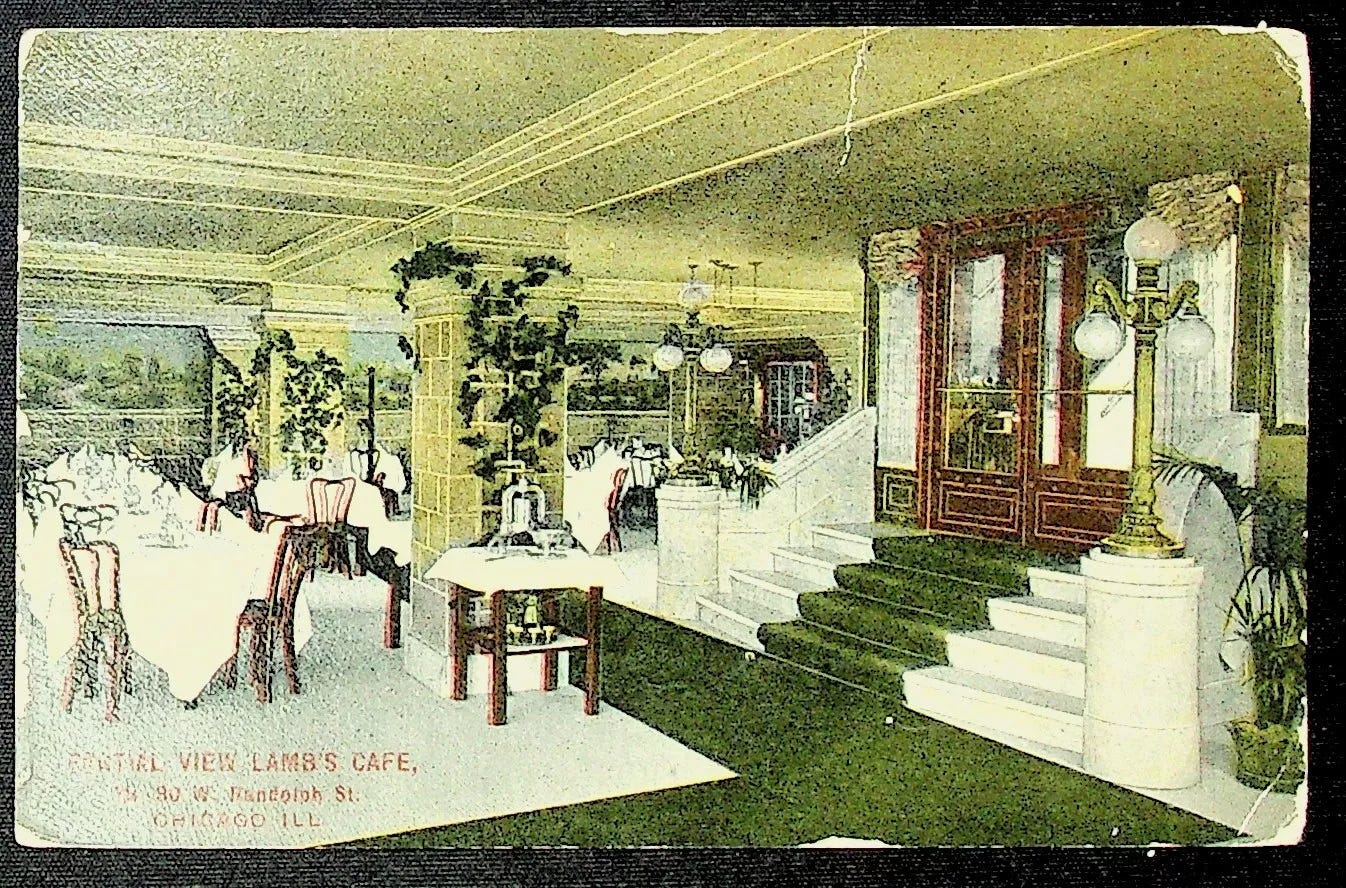

That is first documented in Chicago. A group of white musicians from New Orleans, led by trombonist Tom Brown, arrived at Chicago in May 1915 and by mid-May they were playing at Lambs’ Café. (It was always spelled “Lambs’” in the newspapers. It was not related to the famous Lambs Club which still exists in Manhattan.) They were in residence there from May 17 through August 27 or 28. Before then the Café had presented other kinds of music for dancing, most recently, from May 3 through about May 16, Rigo and his Royal Hungarian Orchestra. Here is a rare postcard photo of the Café’s interior:

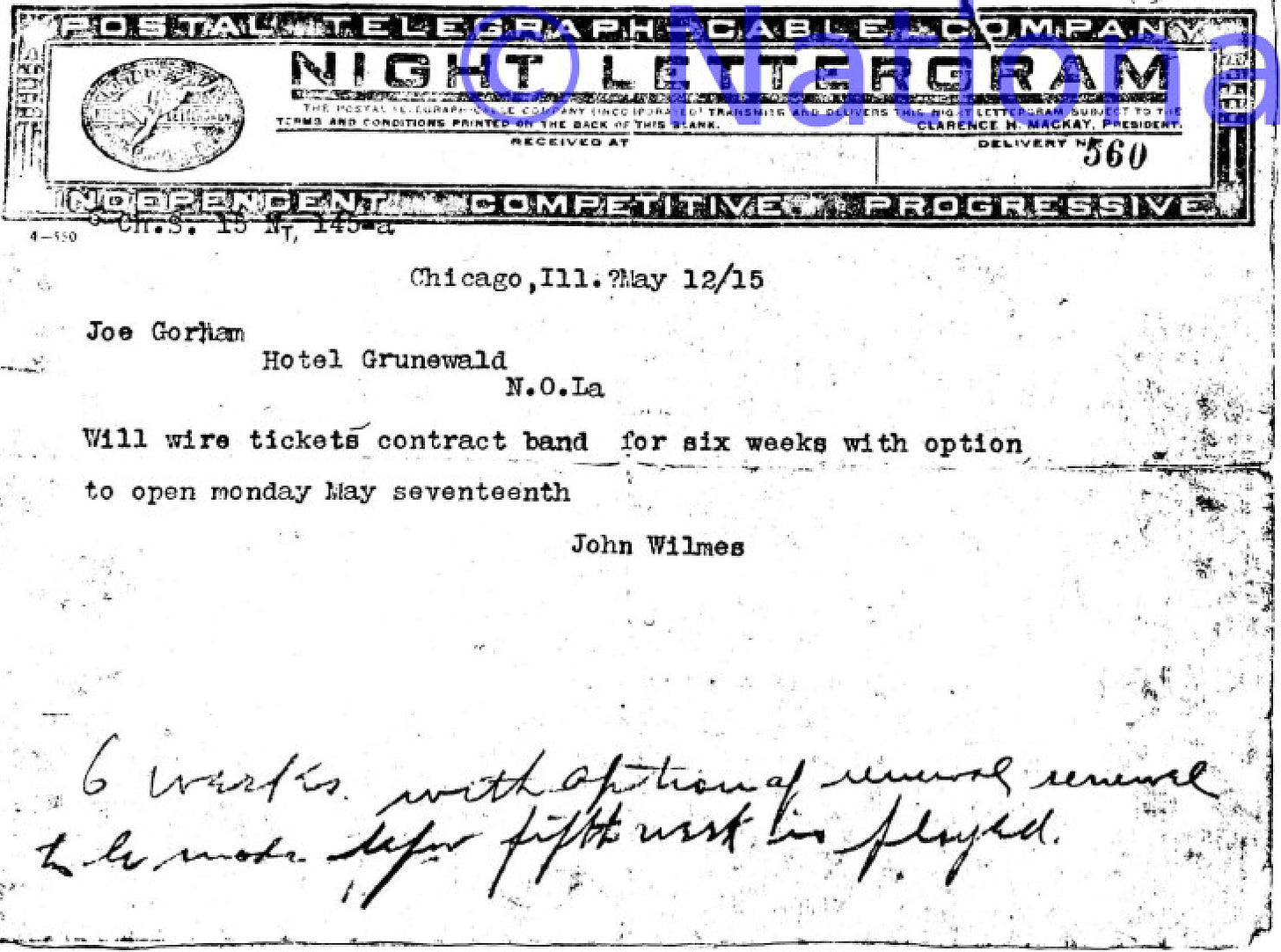

We even have the telegram that offered to job to Brown’s band, sent from the Café by John Wilmes to promoter Joe Gorham in New Orleans. The handwritten note says, “6 weeks with option of renewal; renewal to be made before fifth week is played.” (I added the semi-colon for clarity. The blue stamp on top is from an archive, not on the original.)

Now, Brown always claimed in later years that his was the first band to be called a “jazz band.” For example, you can hear him say so here, reading from a statement that he wrote in the third person on June 3, 1955, and recorded shortly afterward:

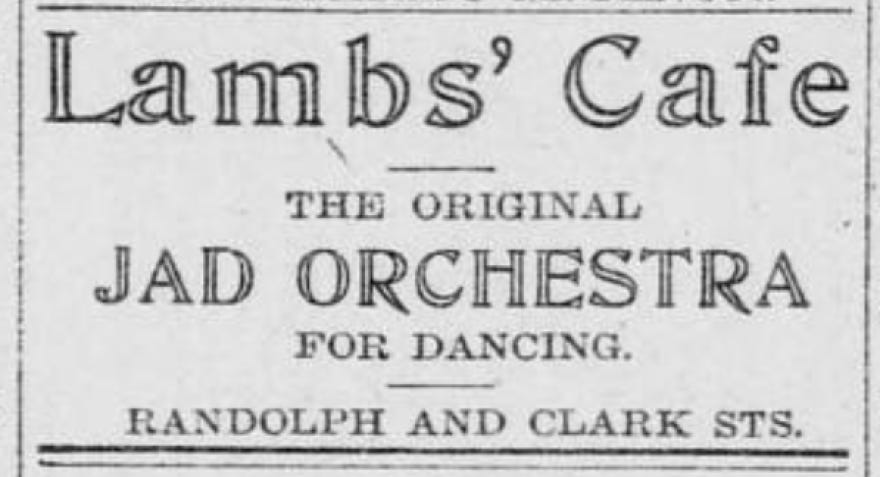

But, frustratingly, in the first newspaper ad for the group, in the Chicago Examiner on May 22, 1915, the band is not named, and the ad does not exactly say “jazz” — it says “Jad Orchestra”!:

Very disappointing for the first ad ever for a jazz band! Where did “jad” come from? Well, in those days one typically spoke what one wanted in an ad, and someone at the office wrote it down. My theory is that the club owner, or whoever placed the ad for him, said “jazz” or maybe even spelled out “j-a-z,” and the person writing it down, who didn’t know the word yet, heard “jad” or “j-a-d.” You might wonder, wouldn’t the person keep asking until he or she got it right? Not necessarily. These people are in a hurry and errors are common—a similar one happened to me as late as 1971. (I’ll tell you about it another time.)

(There is a ridiculous story on Wikipedia and elsewhere that the musicians themselves placed the ad—which is impossible, because it was part of a series placed by the club starting well before Brown came to town. And, the story goes, they were so nervous about using the scandalous word “jazz” that they changed it to “jad,” short for “jade.” As I have already shown in detail, the word “jazz” was not scandalous and had appeared in many newspapers since 1912. And why change it to the non-word “jad”?There is even more to this foolish tale, including union musicians picketing against “jass” and so on. It is completely fabricated. Ignore it, please!)

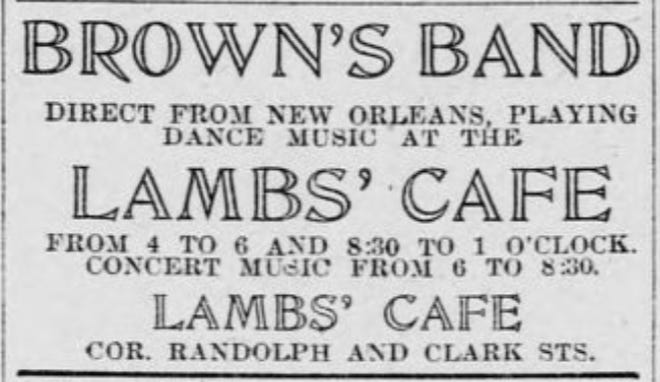

The next ad, on May 26 (the Examiner came out twice weekly), does mention “Brown's Band”—but it doesn’t mention “jazz”!:

At this point, jazz researchers such as myself are tearing our hair out! We have no doubt that Brown’s band was in Chicago in May 1915, thanks to the telegram and the newspapers. And based on what we know of the musicians and their later recordings, they were certainly playing what we would recognize as jazz. But there is no “paper trail” that connects the word “jazz” with Brown’s band in 1915—only “jad,” which is clearly a mistake for “jazz,” but it’s not quite good enough evidence to say that Brown’s was the first to be called a “jazz band.”

But the word was indeed associated with music right around this time: On July 11, 1915, there's a full article in the Chicago Daily Tribune about “jazz and blue(s) music,” which is in itself historic, because here “jazz” refers to a type of music! (“Blues” had already been known as a type of music since at least 1908. This article was discovered by Fred Shapiro, editor of the New Yale Book of Quotations and the leading contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary.) But no specific bands are mentioned. And it’s primarily a humor piece, fun to read but not essential for our tale, which is already quite long! The author considers jazz and blues to be pretty music the same thing. If you’re interested, Chicago historian Robert Loerzel does a deep dive into the article and its author here. (Also, the article is in the Bonus below for Paying Subscribers.)

Meanwhile, as lexicographer Ben Zimmer has noted, white banjoist Bert Kelly (1882-1968) disputed Brown’s claim. He said that he was the one in Chicago who led the first group to be called a “jazz band.” Hmm—maybe. Let’s discuss Kelly’s version next time!

All the best,

Lewis

(Paying Subscribers, at the bottom is a rare print interview with trombonist Tom Brown.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.