Amiri Baraka (1934-2014) was a celebrated poet, a playwright, a founder of the Black Arts Movement, and a prolific and influential writer on jazz. (Those writings included the acclaimed book Blues People—mostly about jazz, despite the title—and two book collections of his short essays on jazz, as well as numerous short magazine pieces.) He was controversial, but the Wikipedia page linked above strikes me as quite unfair, because it quotes things that he wrote in his 30s as though he still believed them in his 70s. He was constantly changing, and over the years he often made extreme statements, in the heat of the moment, that he later softened. But his Wikipedia bio does not reflect that.

I found him to be warm, highly intelligent, and witty. Mr. Baraka was born in Newark, New Jersey, and he returned there in his later years. I got to know him when I taught jazz at the Rutgers campus there. I was at his house once, and we sat together at a jazz memorial event at Saint Peter’s Church in Manhattan. I asked him to be a guest speaker in my graduate seminars four times during the 2000s. For Dr. King’s birthday, let’s listen to the first hour of one of those conversations, held on October 29, 2010. I thank my former grad student Steve Beck for sharing the recording, and my friend James Accardi for improving the audio quality. There is distortion when everyone laughs loudly, but otherwise the sound is clear.

The main focus is on the political nature of music. (As noted below, he talks about Malcolm X and Dr. King starting at 47:40.) The recording begins with Baraka explaining that he briefly moved back to Newark after he was discharged from the Air Force for “Communist leanings.” He discusses his family, his childhood, and his education. Around 3:30 he describes his experiences at the end of the 1950s when he moved to Manhattan and worked at a jazz record shop in Greenwich Village. There he got to know Martin Williams, Larry Gushee, Dan Morgenstern, and others when they were first becoming known for their writings on jazz. The store was also the home base of the jazz magazine The Record Changer, which went out of business in 1957. At the time that Baraka worked there—under his previous name, LeRoi Jones— their only publication was a monthly list of records for sale by collectors, called The Record Trader, which had previously been incorporated into “ ..Changer.”

Around 8:00 he discusses favorite musicians, including famous Newark artists Sarah Vaughan and Wayne Shorter, as well as local names such as Nat Phipps. Hank Mobley and the real Freddie Freeloader are remembered at 10:45. At 13:00, Baraka describes how his studies under Sterling Brown at Howard University, with classmate A.B. Spellman, led to his essays that later became his influential book Blues People. Connections between music, culture, and politics are discussed at length from 14:00 onward. Starting at around 25:30, some of the subjects touched upon are Stanley Crouch, Jazz at Lincoln Center (JALC), Wynton Marsalis, and Ira Gitler’s dismissal of music that is political. Baraka is critical of all of these. (By the way, I was the first to bring Baraka to speak at JALC when I had the opportunity in 2006.)

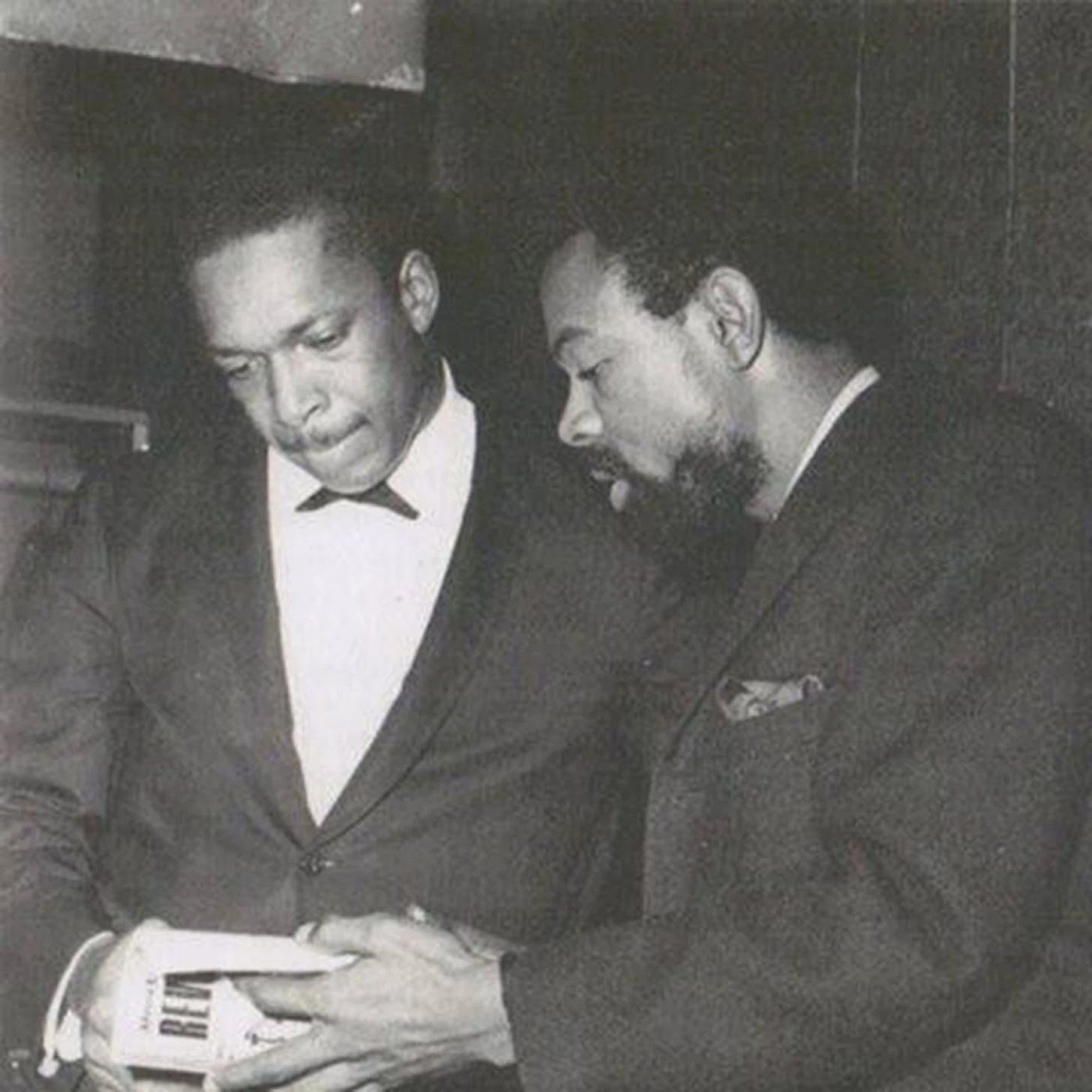

Baraka wrote the original notes for the album Coltrane Live at Birdland, recorded in 1963, and at 34:25 he discusses how Coltrane avoided talking about his piece “Alabama,” even though the meaning was apparent. (I wrote a detailed analysis of that song here.) Below is a photo of Coltrane and Baraka together. The periodical that they are looking at has been identified by my friend and subscriber Francesco Martinelli, a leading jazz historian in Italy and editor of The History of European Jazz. It is Revolution magazine, one of several that have used that name.

You can get more info about this magazine here, and Francesco has shared a photo of a sample issue as well:

At 35:20, Baraka postulates that Ellington might have done something similar to Coltrane when he named his 1926 composition “East St. Louis Toodle-O” (later spelled with two O’s). Baraka sees it as a coded reference to the East St. Louis race riots of 1917. But Baraka was not primarily a jazz historian, and this theory is unlikely. Right after that he wrongly assumes that Ellington wrote his own lyrics for “I’m Beginning to See the Light” (and, by the way, it was not written for Duke’s show Jump for Joy).

At 38:00, he talks about working on his friend Max Roach’s memoir, which remains uncompleted in the Roach collection at the Library of Congress. And from 47:40 onward he talks about Malcolm X, whom he knew, and Dr. King, who he met once, and about the reactions to each of them within Baraka’s circle. Let’s listen:

I recognize the voice of my former graduate student Alex Rodriguez (now a Ph.D. with an interesting newsletter) at 25:27 and 45:00.

There’s another half hour to this fascinating conversation, which we’ll hear next time. In it, Baraka talks more about Dr. King and Malcolm X, then speaks at length about Sun Ra, with an excerpt from a recording they made together, and about poetry itself, and Langston Hughes. See you then!

All the best,

Lewis

Excellent!

Whatever people say and whatever he said elsewhere, Blues People is a breakthrough foundational work. Thanks for your wise and respectful presentation of Baraka.