(NOTE: This is the third in a series examining Billie Holiday’s improvisational skills. I was shocked to realize that out of the hundreds of articles and books written about her, I do not know of even one other writing that points to specific measures from specific recordings to analyze Holiday’s musical genius. Here is Part 1, and here is Part 2.)

The best resource on Billie Holiday’s recordings and films is https://billieholiday.be. Here you can research every recording of a particular song, find all the recordings where she works with your favorite musician, compare every CD and DVD release, find audio clips in some cases, and more, regularly updated.

Now, let’s continue our study of her improvising: There is a perception that by the 1950s, Billie was more of a cabaret artist, polishing each performance to a “T” and not improvising. (Note: The expression is letter “T,” not “tee” as in golf.) This may have been true with some numbers, but it was certainly not true of most. For example, let’s listen to a few of her versions of the classic song “All Of Me,” recorded from 1941 to 1954.

First, for comparison, here’s Frank Sinatra in 1947 singing the first four phrases of the lyric (the text of a song) fairly straight, though he certainly puts some personal expression into the word “me”:

The first time Billie recorded it, Take One in March 1941, she sings the first four phrases of the melody pretty much as written. But even so, at the end of the second phrase--the one that goes “Why not take all of me?--she adds some embellishment. And on the line “I’m no good without you,” she stretches out the word “no,” which somehow gives the statement more power:

On Take 3, she produces a totally new melody, especially on phrases 1,3, and 4--and it’s a beautiful melody that communicates deep emotion:

Now let’s hear her soaring final chorus from Take 2, recorded within a few minutes of Takes 1 and 3. First, we hear the last notes of the sax solo by her favorite, Lester Young. Those last notes can’t be avoided because they overlap with her vocal—you and I don’t mind the overlap, but that is probably the reason that they went on to do a third take. (On Take 3 there is no overlap.) Let’s listen:

Her voice in 1941, with a full tone and strong vibrato, is miles away from her 1950s voice that people love to imitate—and which, for many, is the only Holiday that they know! However, we only understand and appreciate her later style because we’ve followed Holiday through the years.

Hear, for example, how she could communicate with an all-star band in June 1944. This complete performance is taken from a civil rights radio series entitled New World A-Coming, inspired by the 1943 book of the same name (as was Ellington’s piece of the same title). The book’s author was the distinguished Black journalist, now forgotten, Roi Ottley. Holiday’s arrangement (yes, she had a big role in designing her arrangements, as I’ll show in future posts) was short and sweet—two choruses, the second building on the first, no instrumental solos. Here we are in June 1944, with Art Tatum at the piano, and with Ben Webster, Roy Eldridge, and other artists in the background. But let’s listen later to what’s going on behind her. On your first listen, please focus on Billie—notice that she has added “Hey, Baby” right at the end:

The audio quality is not great on that one, but as always Billie’s brilliance comes through. Here is another beautiful—and this time, well-recorded-- performance, on stage at Carnegie Hall in 1946. This one has a different “all-star” cast, produced by Norman Granz under the heading “Jazz at the Philharmonic” (JATP). There are two or three tenor saxophonists on stage at once—Pres (Lester Young), Georgie Auld (that’s him behind her at the beginning) and possibly Illinois Jacquet (he was also on the bill)! She sings “Hey, Baby” again at the end—it has become part of her arrangement:

Now let’s jump to February 1954, during her first European tour, again on a bill with other artists, this time under the heading “Jazz Club U.S.A.” The tour was named after the radio show of jazz journalist and composer Leonard Feather, who produced the busy schedule of about 30 concerts. He was a dedicated supporter of women in jazz, so he hired pianist Beryl Booker, and asked Booker’s drummer Elaine Leighton to also support Holiday. Here’s a photo of Billie at the Salle Pleyel in Paris on February 1, 1954, with her regular piano accompanist Carl Drinkard, bassist Red Mitchell, and Leighton:

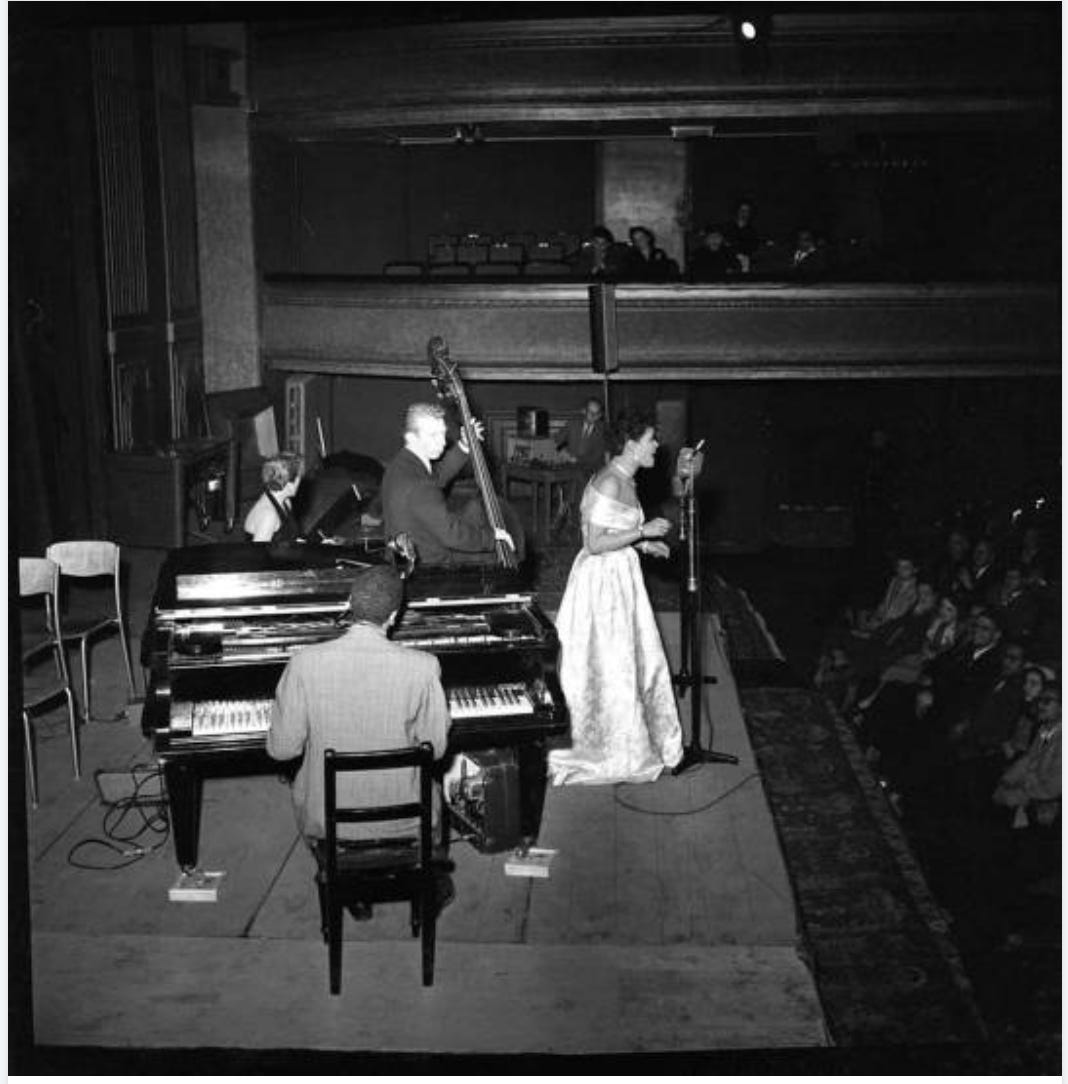

And here’s a view from the side, taken at The Hague on January 31, 1954, by Wouter Van Gool:

At the concert in Basel, Switzerland, she takes a much faster tempo than in the ‘40s, and her approach to the song is totally different—very conversational, very improvisational. Her voice has some of that hoarseness that we identify with her last years, and it’s very appealing. I love the “sing-songy” way that she does “Why not take all of me?” right at the beginning. Notice the way she combines the “Take my arms” phrases into one longer phrase, at 0:23-27 and at 1:07-1:11. “Hey, Baby” is still here, and now she has added some breaks (where the band stops) at 1:22 to the end. Here it is, complete:

(NOTE: In the Complete Billie Holiday on Verve boxed set this is mistakenly listed as being from the Cologne concert of the same tour. It’s from Basel.)

Finally, let’s compare one more short but complete version of “All of Me,” in front of Count Basie’s big band at Carnegie Hall in September 1954. It’s a bit slower than the one we just heard. As one might expect, a lot of the details are similar to the Basel recording of seven months earlier, but there are subtle differences too. How about the expressive way that she “half talks” the words “How can I go on?” at 0:34 and 1:17? The breaks appear again at the end, made more dramatic by the big band setting:

It works, scratchy voice and all, because we know who she is. But for those who only know recordings like this, and don’t know her earlier recordings, they are missing a lot of very important information!

(By the way, as was and still is standard practice, Billie brought her pianist of that time to play with the big band in place of Basie. It was Memry Midgett—that was her real name! I believe that Billie had an interest in women instrumentalists, something I’ll discuss another time.)

As I said in Part 1, Billie certainly could not scat the way Ella Fitzgerald could. And she never scatted in performance, only in rehearsal to demonstrate something to her musicians.

And as I’ve also said, singing was serious business for her. It would have made no sense for her to break out into scat in the middle of a song, even if that worked for Ella and some other singers. For Billie Holiday, singing was about the lyrics, and about telling a story that came from life.

But did she improvise, right up to her last performances? You bet she did, with daring and originality. And was she telling the truth that she didn’t sing the same way twice? Most of the time, absolutely yes.

I’ve got much more on Billie (and everybody else)—coming soon!

All the best,

Lewis

Brilliant! Analysis like this give, at least me, a much deeper insighht in Billie Holiday's artistry even though I have loved her works for over half a century.

Lew - is it safe to assume that Elaine Leighton was chosen by Billie then as well? Early 50s was still relatively uncommon to see a touring female kit player. At least, that's my presumption. Correct me if I'm wrong.