Billie Holiday: There was Never a Federal Campaign against "Strange Fruit"--Part 3 of 4, UPDATED

The Reception of “Strange Fruit”

Sorry—I am always researching, and sometimes I make slight edits after I’ve already posted an article. In this case, I found a news clipping—Attached below—that strongly adds to my case. You might consider checking back now and then for updates.

(NOTE: This series is an expanded version of my article that was originally published in Jazz Times magazine, and I thank the editor Mac Randall for his fine work. Here is the original article, winner of the 2022 Virgil Thomson Award for Outstanding Music Criticism in the pop music field.)

In Parts 1 and 2, I showed that there was no government campaign against “Strange Fruit” (and I provide even more evidence below). And I showed that the falsehood that there was such a campaign was invented by a discredited British author named Johann Hari, who has no background in jazz.

So, how in fact was Holiday’s recording received? There’s plenty of evidence that “Strange Fruit” was not suppressed, and it was never officially banned in the U.S.A. (I’ve heard people say it was banned in the U.S.A., but they are simply repeating a rumor. However, according to David Margolick, in his book Strange Fruit, it was indeed banned on BBC radio in the U.K. at one point, and in apartheid South Africa.) On the contrary, the recording was well known, and even celebrated in some circles.

Billie recorded “Strange Fruit” on April 20, 1939, and it appears to have been released by early May. (Such a quick turnaround was common for 78 rpm records, since they were released in brown paper sleeves—no cover art, no notes!) In her book with Dufty, Billie says it “became my biggest-selling record.” That’s possible, although it is difficult to get sales figures from that long ago. For example, You will read on various websites that Holiday had more “top 10” recordings during the late 1930s than she did later, but in the late ‘30s “top 10” could mean for radio airplay, or for jukebox plays, or even for sheet music sales, or a combination of all three—but rarely if ever for actual sales of the 78 rpm recording! In terms of actual record sales, it’s possible that in the 1940s “Lover Man,” “God Bless the Child,” and “Travelin’ Light” sold in much higher numbers than “Strange Fruit.” Still, the bottom line is that “Strange Fruit” was without a doubt very successful.

(Side note: Billie’s memoir is a mixture of things, but it does contain many of her own words and, contrary to what some have written, she was very involved in writing it. That’s another topic for another time.)

Billie herself says in her book that the success of “Strange Fruit” was what enabled her to move from the small Commodore Music Shop company to a major label, Decca. Time magazine offered a short piece about the Commodore recording as early as June 12, 1939, in which an anonymous staff member wrote, “Unsqueamish, the Commodore had not balked at recording Teacher [Lewis] Allan's grim and gripping lyrics.” And here is what the announcer says on her earliest surviving “live” radio broadcast of “Strange Fruit” in 1939 (part of the Savory collection, unissued), just after the recording was released: “Billie Holiday in person, singing the song that is driving swingsters crazy as they play it over and over on their phonographs. It has a very strange and haunting effect on most people. It’s ‘got’ me, so let’s see if it will ‘get’ you.” (You can listen to this announcement, and the performance that follows, here.) This was hardly the way to introduce a banned song—on the contrary, it was clearly a number with a fast-growing “cult” following.

It’s well known that her label, Vocalion, which had been bought by Columbia in 1938, declined to record the song, but once it was released, and proven to be a success, the song was not viewed by Vocalion and other record companies as a dangerous political statement, but rather, as the above quotes suggest, as a grim, gripping, strange and haunting lament. Although it has rarely been noted, there were attempts to follow up on the success of “Strange Fruit.” And they were not political songs, but rather attempts to recreate the mood. The first one, I believe, was “Ghost of Yesterday,” recorded in February 1940, which had such lyrics as “profound gloom…mournfully, scornfully dead, Folly of a love I strangled.” Next, in August 1941, was “Gloomy Sunday,” written in the voice of someone planning to “end it all.” A few years later, in February 1947, came another in this genre of “haunting laments” called “Deep Song,” which began “Lonely grief is hounding me.”

Now, I’ve already debunked the false claim that Anslinger and the FBI were after Holiday specifically because she sang “Strange Fruit.” But here are more details for you: Holiday’s FBI file is a mere 10 pages, and it is entirely devoted to her arrest in San Francisco in February 1949 (she was later cleared). The only other government files on Holiday are the separate court records, and the file from the prison that she was sent to in 1947. Stuart Nicholson went through all of these closely when writing his well-researched Holiday biography, and he found no reference anywhere to “Strange Fruit.” This is consistent with what other researchers have found regarding other artists. In general, the narcotics-related files from the ’40s and ’50s are solely concerned with drugs, whereas the political files are almost entirely devoted to rooting out communists.

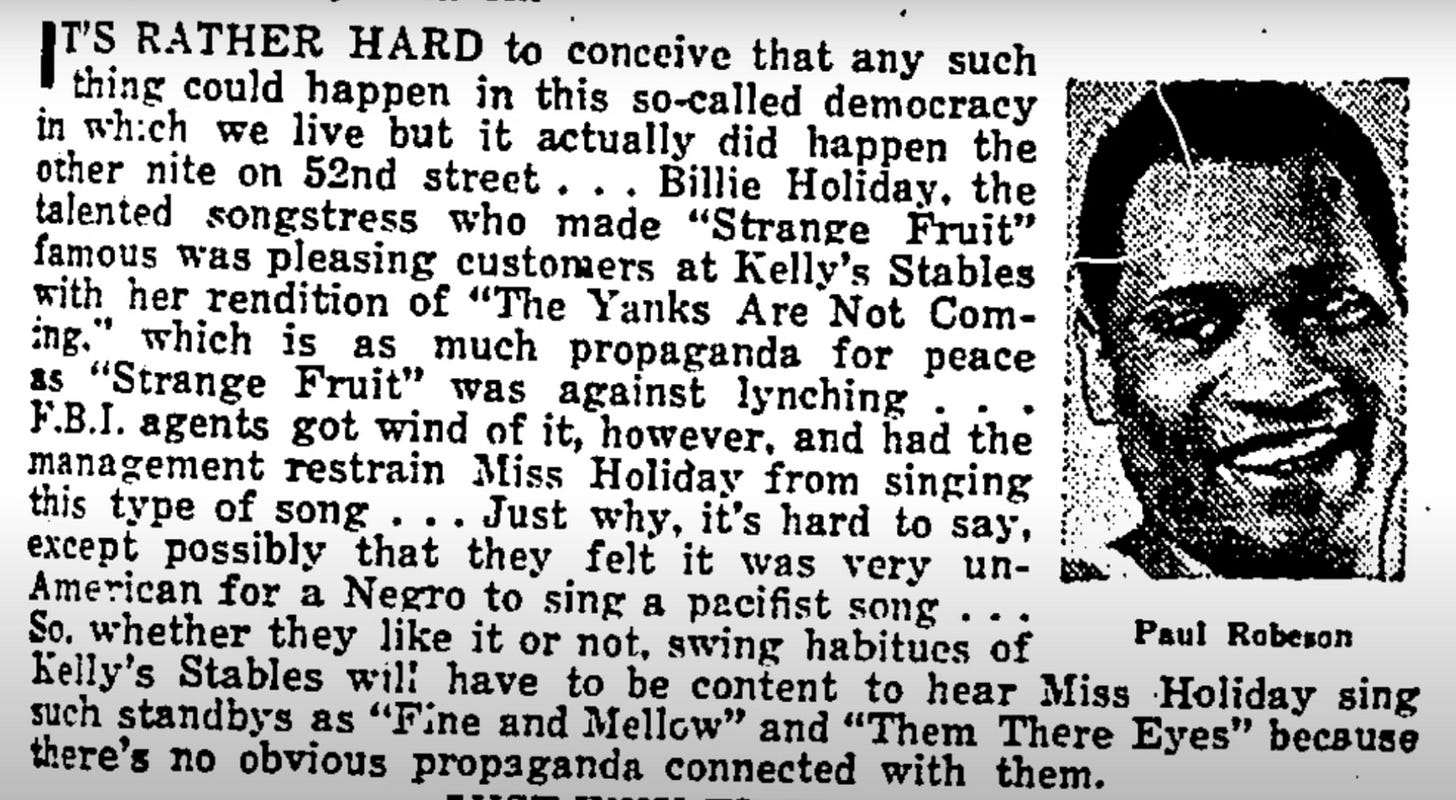

In fact, the one time it was reported (in the Black newspaper The Amsterdam News, August 31, 1940, p.11) that the FBI interfered with her act, it was to ask her to stop singing “The Yanks Are Not Coming,” which argued against the U.S.A. getting involved in World War II. This song was particularly controversial because it was promoted by the American Communist party. It was a “spoof” of a World War I song, “The Yanks Are Coming.” The FBI agents ignored “Strange Fruit” altogether, even though she was singing it as part of the same engagement! Here is the relevant part of the article:

With regard to “Strange Fruit,” it was not Holiday, but the composer, Abel Meeropol (pen name Lewis Allan), who attracted government interest, because of his activity in the Communist Party. During a 1941 New York State investigation of supposed communist infiltration into education, Meeropol was subpoenaed and asked, among other things, whether he had ever been paid by the Party to arrange a performance of “Strange Fruit.” (He said no.) His FBI file notes that he had presented the song at the Theatre Arts Committee, which they considered a “communist front.”

As for Holiday, other than the incident cited above, the Bureau of Narcotics went after Holiday not for her politics, but as a “role model” drug case. Its strategy was to pursue “high profile” users so as to discourage their fans from copying them. Her file explicitly says: “… [I]t has been the policy of this bureau to discredit individuals of this caliber using narcotics. Because of their notoriety it offered excuses to minor users.”

And Hari is wrong again when he suggests that Anslinger only targeted Black artists. The agency’s most high-profile arrests were of drummer Gene Krupa in 1943 and actor Robert Mitchum in 1948. Both were white, and neither was political. Also, despite claims in Hari’s book, it’s not true that Judy Garland was treated gently because she was white, nor that she was using heroin. She was abusing prescription drugs—sleeping pills and amphetamines—not illegal drugs, so Anslinger had no case against her. He did go after her doctors instead, but she then foiled him by finding other doctors.

Was there pushback against “Strange Fruit” from sources other than the government? Absolutely, but not anything organized or official. Sometimes it came from people—audience members, club owners, or radio DJs—who didn’t like the message. Sometimes it was from people who had no problem with the message, but felt it was out of place in their program of dance music, similar to what happened at the Earle Theater (see Part 2). Sometimes it was from people who didn’t get the message and weren’t even sure what the song was about! David Margolick, in his book Strange Fruit, gives a number of examples of such situations, and confirms that the song was never formally “banned” anywhere in the U.S.A. He also notes that, because of such incidents, Holiday’s performance contract from about 1949 onward stipulated that she must be allowed to sing it if she wanted to, that is, that she could overrule the venue’s managers. If this is true, it’s yet more evidence that the government had not issued an “order” against it, and that Glaser, the manager who sent out her contracts, had no problem with it.

In fact, by January 23, 1949, an article was syndicated in many newspapers that said: “…Her recording of ‘Strange Fruit,’ the weird minor-key lament of a Negro lynching, has become her virtual trademark.” That’s two years after 1947, the year that Hari and the movie falsely claimed that she was ordered not to sing it.

Well, I think I can rest my case that there was no government campaign against “Strange Fruit.” But the makers of this film also dreamed up numerous other fictions, some of them so implausible that they would be hilarious, if it weren’t for the fact that people believe this movie to be based on fact. In the fourth and final section, I will review just a few of the many, many other fabrications in this movie.

(And after I post Part 4, I’ve got lots more posts ready to go about topics other than the great Billie Holiday.)

*Really* digging this series. In an age of fake news and hogwash pseudo-facts, it behooves those with the energy and wherewithal to uncover the truth. And it by God behooves the rest of us to *listen*--and be grateful Thank you, Lewis, THANK YOU!