Charles Mingus Writes A Letter About His Recordings, Part 2 of 2,+Bonus

(Paying Subscribers, your bonus is at the very bottom again.)

You have read a long letter from Charles Mingus in Part 1. In it he refers to many things that will be unknown to even the most devoted Mingus fans. So I’ll address those here. For your convenience, I’m attaching the letter again, below. Let’s start with the first page:

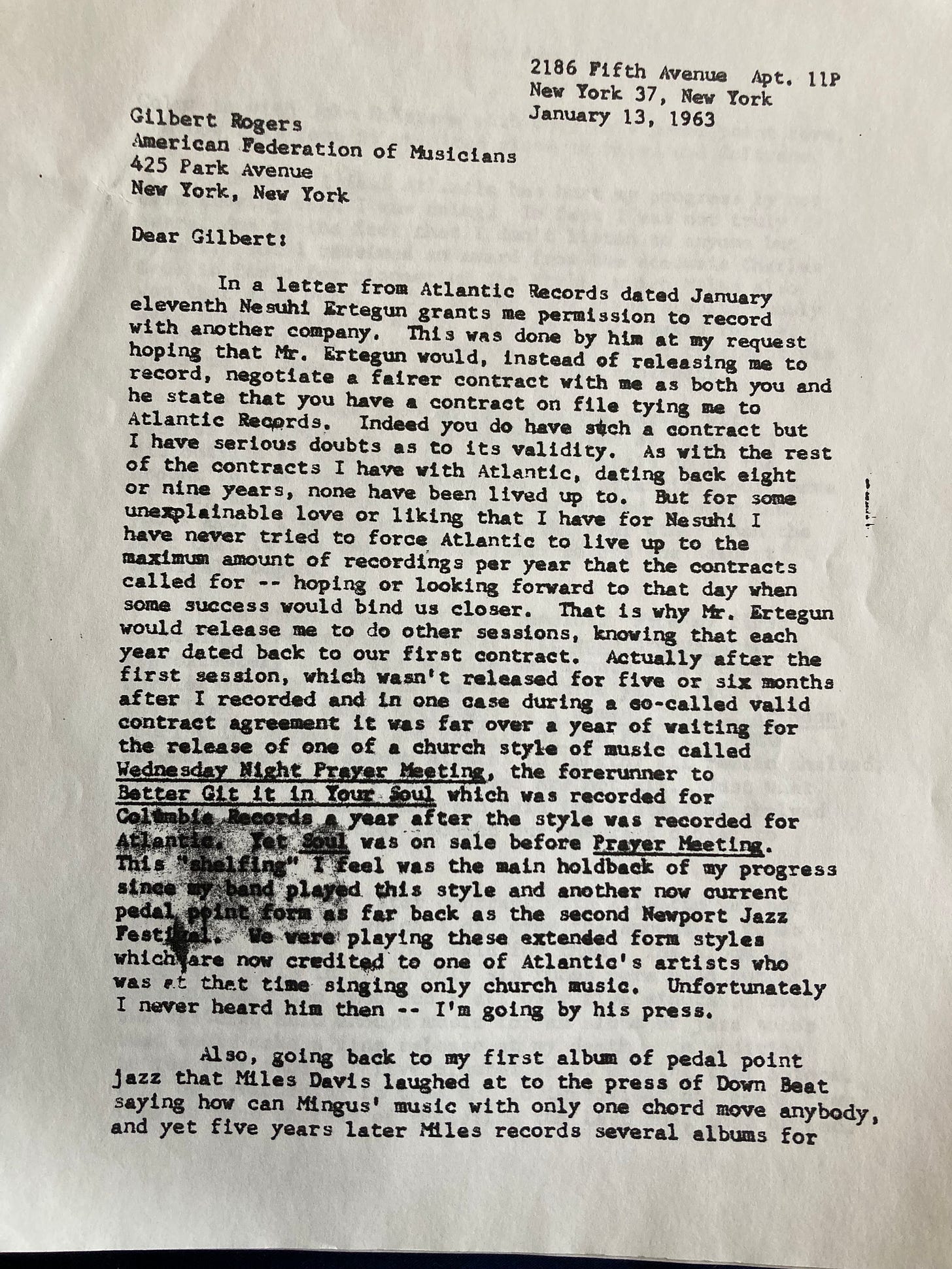

At that time the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) office was at 425 Park Avenue, between East 55th and 56th streets in Manhattan. That building had opened in 1957, and was torn down beginning in 2015 and replaced with a new building over the next few years. The AFM is now at 1501 Broadway in Times Square (and the AFM Local chapter 802 is on 48th Street).

Mingus’s home address in 1963, 2186 Fifth Avenue, was at Lenox Terrace, a group of six buildings between 132nd and 135th streets. The first one was completed in 1958, so they were new at the time, and considered to be among the nicest in Harlem.

Mingus starts by saying that Ertegun agreed to let him record for another label, but that he had actually hoped that Ertegun would have said, “Instead of recording for someone else, let’s put out another Atlantic album.” He says that Atlantic has not lived up to its contract, because it hasn’t released as many albums as were promised. (If this is true, why did Ertegun not release more? Were sales not as good as he’d hoped?)

For example, Mingus notes, the album Blues and Roots was recorded in February 1959 but not released until March or April of 1960. Meanwhile, at the suggestion of his old friend Teo Macero—he had played saxophone with Mingus and was now a producer at Columbia—he had signed a one-year contract with Columbia. (Apparently the Atlantic contract had just expired, and Mingus chose not to renew it.) The Columbia album Mingus Ah Um was recorded in May 1959 and was released in October 1959. The result was that the Columbia album’s opening track, “Better Git It In Your Soul,” was available well before “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting.” But Mingus had intended them to be released in the order recorded—“Wednesday Night…” followed by its sequel, “Better Git…” (Sorry if this is getting complicated!)

(Trombonist Dan Weinstein points out that a version of “Wednesday Night…” was actually released in 1958—but it was only played briefly behind Langston Hughes reading his “Dream Montage” poems, and not listed on the album—only the next tune, Mingus’s “Jump Monk,” is listed. So I think it’s fair to say that doesn’t count.)

Mingus calls this an “extended form style,” by which I think he means an open-ended arrangement where you can repeat sections on the spot, as you wish. He mentions an Atlantic artist who used to sing “church music” and now gets credit for this style. (He means Ray Charles, but Charles never really performed church music, although his music exhibits a definite gospel influence.) In this way, he argues, the delay hurt his reputation, because now Ray Charles gets the credit for something that Mingus did first.

But, as U.K. jazz historian and pianist Brian Priestley explains in his detailed Mingus biography, probably the delay of the release of Blues and Roots was caused by Mingus signing with Columbia! Priestley points out that Blues and Roots had been assigned an album number, but that albums with higher numbers came out first. This indicates that they had planned to release it in the summer of 1959, but then held back when Mingus recorded in May for Columbia, knowing that they could not compete with the giant marketing machine of Columbia Records. It seems unlikely that Mingus didn’t know this.

Mingus’s other example is more justified. He claims, truthfully, that he had been using the “pedal point form”—what people today call “modal jazz”—before Miles and Coltrane, but that because his recordings were not released at the time, only Miles and Trane got the credit. (He says that Miles recorded “several albums” of modal jazz with Coltrane, which seems to be a bit of an exaggeration. There was Kind of Blue and the title track of Milestones—plus Sketches of Spain without Coltrane.) He notes that this is especially ironic because Miles initially said a few years earlier that he was skeptical of “one chord” jazz. (That sounds familiar, but I can’t find where Davis said that.)

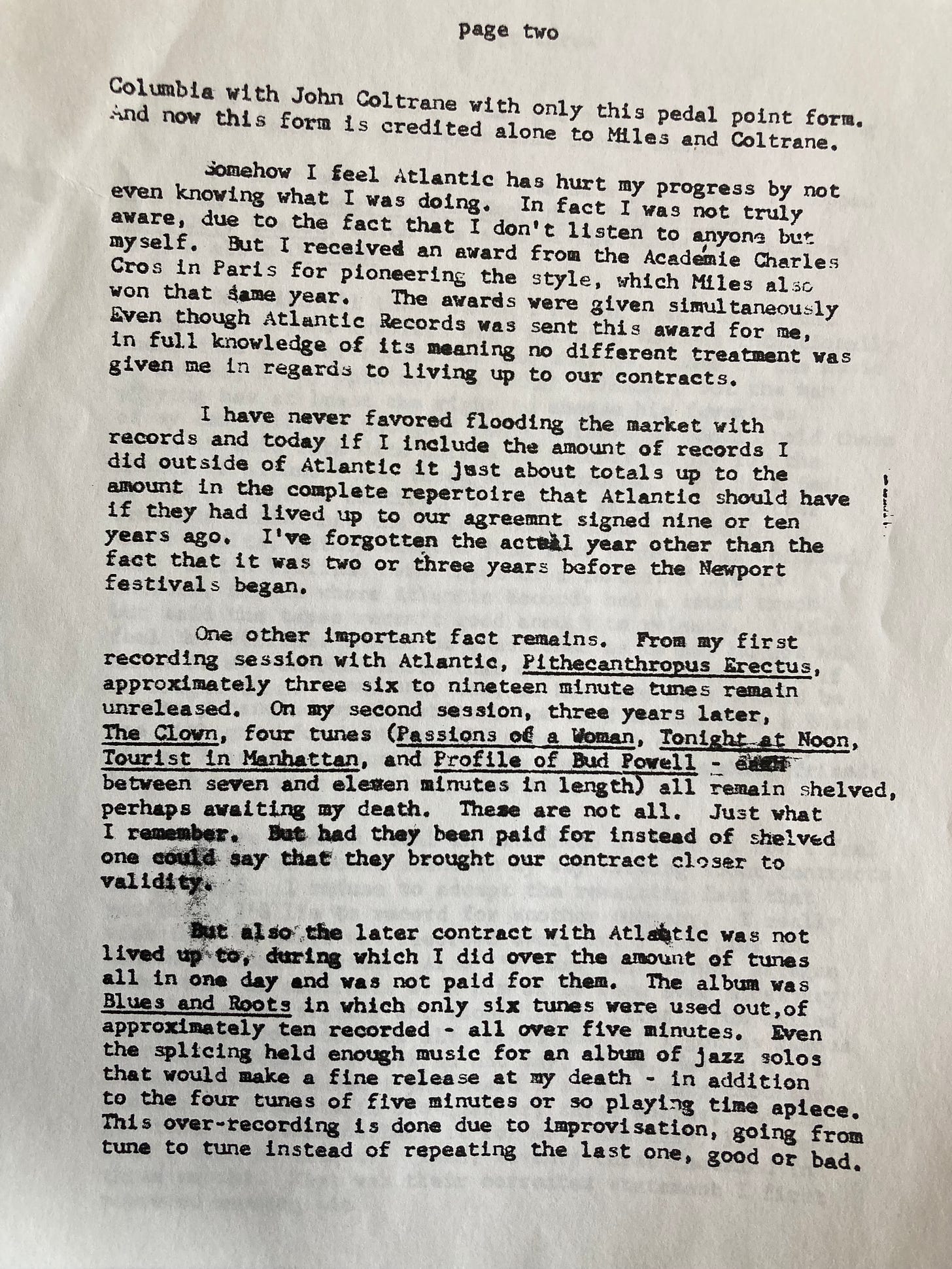

Mingus understands that one can’t “flood” the market with recordings, but he feels that the opposite has happened—that Atlantic has released so few of his albums that he has to get permission to record for other labels just to put out a reasonable number of albums. He is especially frustrated because he feels that he has recorded enough for Atlantic for them to put out more albums. Toward the bottom of the second page, he notes that there is quite a bit of unreleased music. Let’s review that page again:

The wording after “One other important fact” might seem a little unclear. He means that from the album Pithecanthropus Erectus there are three unreleased pieces, ranging from 6 to 19 minutes in length. He gives the titles of four unreleased titles from The Clown, and says sarcastically that the label is “perhaps awaiting my death.” Two of them, "Passions of a Woman (Loved),” and "Tonight at Noon,” were released around June 1964 on an album named for the latter piece. Maybe that was a result of this letter, among other things which we will see.

He notes that there were about four more titles recorded for Blues and Roots—and he clearly is not referring to the four alternate takes (which were released in 1997 on the complete Atlantic boxed set), because in those days one never released two takes of the same tune. He notes that some solos were spliced out to keep the pieces from getting too long, and says he allows this “over-recording” because it’s “the only way I can get a true live feeling.” This is one of several places where he suggests that studio recording is a necessary evil, very far from the ideal way to present his music. He cynically suggests that all these omitted solos would “make a fine release at my death,” showing once more that he’s well aware that the recording companies like to put out material when an artist dies.

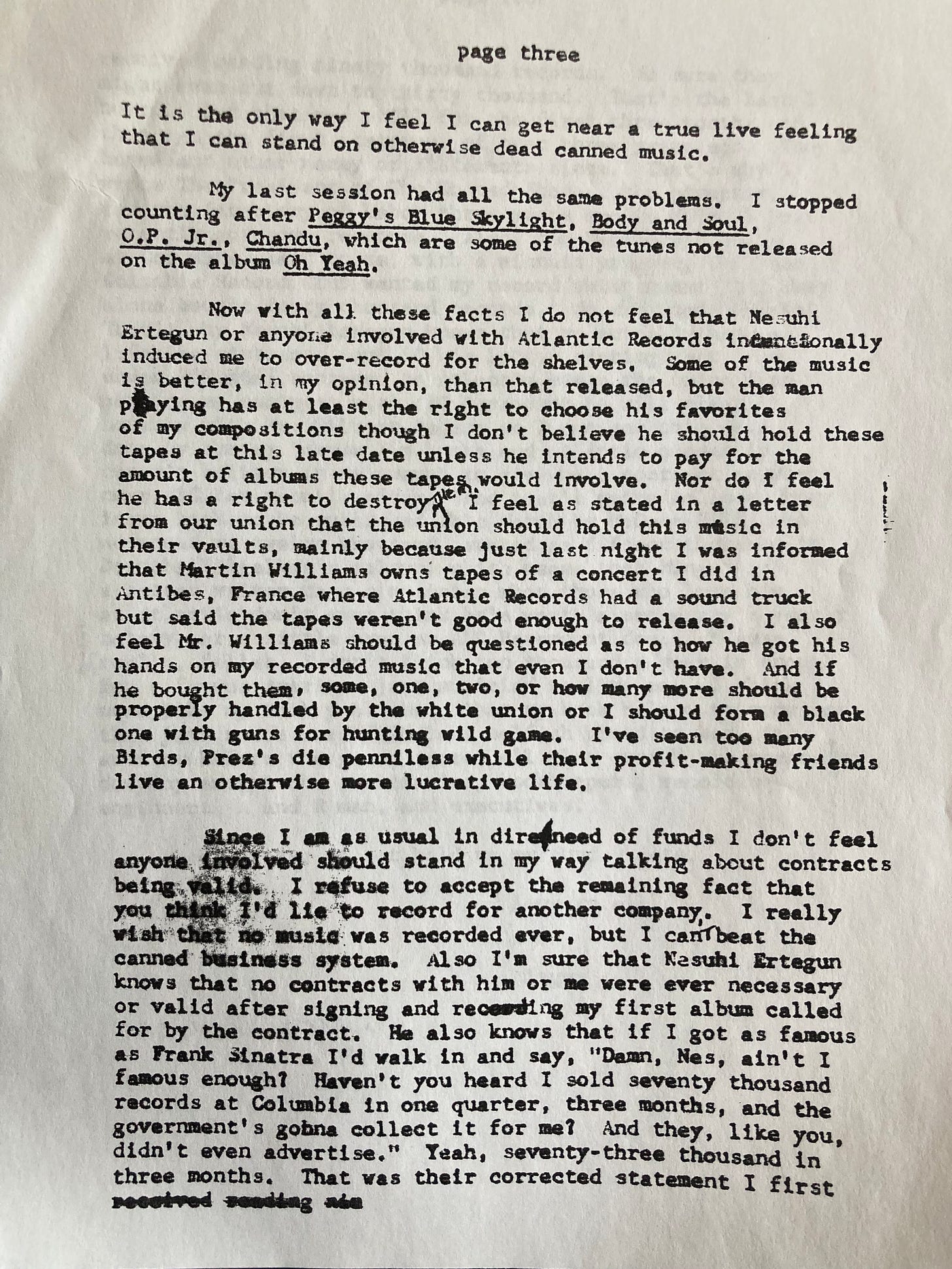

Now, let’s look at page 3 again:

He also lists four specific unreleased pieces from the album Oh Yeah, which he recorded in November 1961 after he returned to Atlantic. Of those, "Peggy's Blue Skylight" appeared on the album Tonight At Noon in 1964, along with “'Old' Blues for Walt's Torin" and "Invisible Lady." The last two are not among the titles he lists, but he does note that there were others and that he “stopped counting.”

Unfortunately, Atlantic waited too long to release all this music. Famously, a fire in 1976 destroyed most of Atlantic’s tapes. So in 1997, when they compiled Passions of a Man: The Complete Atlantic Recordings 1956-1961, the only new items were the four alternate takes mentioned above. The notes mention six pieces known to have been destroyed in the fire, and if Mingus’s memory is accurate in this letter, there were more at one time. (Don’t get me wrong—Patrick Milligan, who I’ve worked with on other projects, did a beautiful job producing this boxed collection of everything that exists for those years.)

Moving on, Mingus states that he understands that man paying (the producer—notice that at first he typed “playing,” which would mean himself!) has the right to select what will be issued. But he’s concerned that if these items never get issued, he’ll never get paid for them. Further, he’s worried that they might get into the wrong hands in the meantime. He just learned that the well-known critic Martin Williams had tapes of Mingus’s concert in Antibes, France in 1960. (This is the concert where Bud Powell joined the group on one tune. It was released in 1976.)

Now Mingus is angry. He says that the union should be safely storing such tapes (apparently that had been suggested), to prevent them from circulating like that. He says that if “the white union” can’t handle this properly, maybe “I should form a black one with guns”! (As Mingus well knew, New York City never had a segregated musicians’ union. However many other cities once had separate local chapters for Blacks and whites, including Los Angeles, where he had begun his career.) He’s seen too many people like Bird and Pres die penniless.

The bottom of this third page suggests that Mingus and Rogers had discussed this before: He says that he doesn’t feel that “anyone involved should stand in my way.” And he refuses to accept that “you think I’d lie” to get permission to record for another company. And here’s another expression of his distaste for the studio: “I really wish that no music was recorded ever”—it’s a “canned” (meaning pre-recorded, as in “canned laugh track”) “business system.”

Mingus noted on page 2 that his French award did not gain him better treatment at Atlantic. Now he says that his sales are so good, almost like Sinatra, that he should ideally have some power. He sold 73,000 albums at Columbia in 3 months. Let’s go on to the last page, number four:

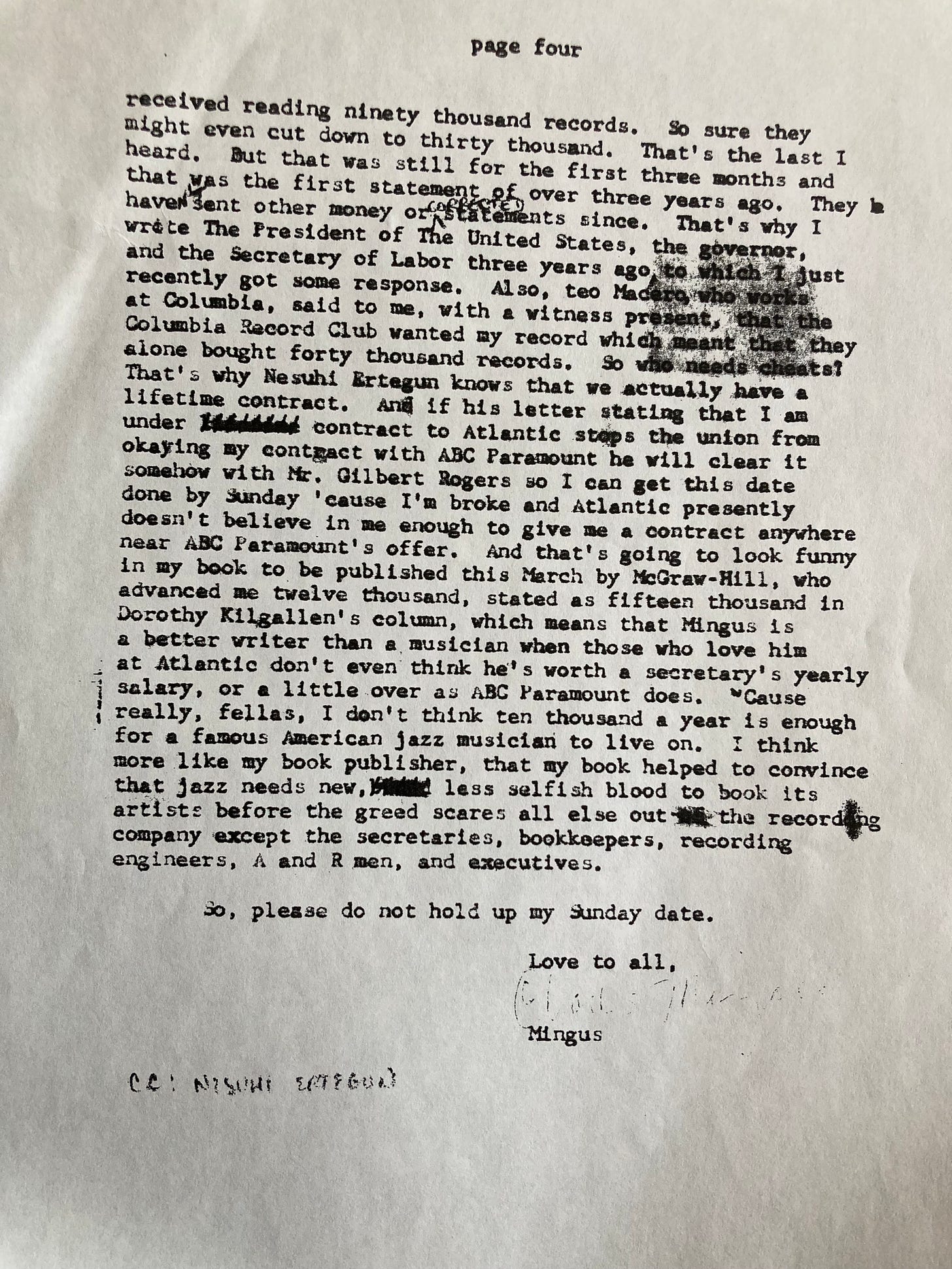

He doesn’t trust Columbia because their first statement said 90,000 sold, and then they said that was an error and they sent him the corrected number of 73,000. And they didn’t send him any money or any corrected statements after that. He wrote to the President, the Governor, and the Secretary of Labor to complain (which let’s be honest, are not the appropriate channels). And his Columbia producer, Macero, said they wanted to offer one of his albums at their record club, which could mean 40,000 sales. (The Columbia Record Club had a huge role in the history of the record business. And Evan Spring informs me that Mingus Ah Um was in fact sold through the club in 1961.) He concludes, “So who needs cheats?” In the lingo of the day, that means, “I don’t have to go looking for people to cheat me, because I’m dealing with them already.” In short, now we know why he didn’t stay with Columbia! He didn’t trust them at all, and he apparently got into big battles with them as well.

Now he’s off on a rant. (OK, maybe he has been ranting all along.) He says he’s back to Atlantic for life (for various reasons, such as the fact that the label was sold in 1967, it didn’t work out that way, but he did return to Atlantic from 1973 until his death). And he trusts Ertegun to get the union to allow him to record on Sunday with ABC/Impulse. Still, he can’t help but berate Ertegun for not paying “anywhere near” what Impulse is offering to him.

Next, he threatens that he’ll tell about all this in his book, which he says will be published in March 1963. (In fact, the book had a long and troubled history, and didn’t come out until 1971. The best account of the history and content of Beneath the Underdog, including how each chapter relates to actual life events, is in Krin Gabbard’s Mingus book.) He informs them that he got $12,000 as an advance against royalties, and that the $15,000 figure cited by columnist Dorothy Kilgallen is an error.

Kilgallen was a devout jazz fan. Her column was mostly Broadway theater news and gossip but she often threw in jazz news as well. You may have seen her on What’s My Line?, where she was a panelist for over 15 years. (Despite what you may read elsewhere, her death in 1965 was caused by mixing alcohol and pills—she was not murdered.) Here is what she wrote about Mingus in her column, which was reprinted in many newspapers around the U.S.A. This one is from the Star newspaper in Oneonta, New York, October 25, 1962:

(Paying Subscribers, at the very bottom of this page you will read the rest of this column, with interesting news items about Joe Morello, Buddy Rich, Barbra Streisand, and others.)

We learn here that Mingus was so discouraged by the music business that he had considered giving up performing. (As I showed earlier, in 1957 Miles Davis also considered retiring from the stage.) And as I noted, she says he received $15,000 but Mingus says it was $12,000. In any case, as Mingus observes in his letter, this means that he makes more money as a writer than as a musician. He says that compared to what a secretary makes in a year, Atlantic offers him less, and Impulse offers only a little more. Then he mentions that $10,000 is not enough for “a famous American jazz musician.” At that time, secretaries generally made anywhere from $5,000 per year, to $10,000 for executive secretaries. (Today of course the position is known as an Administrative Assistant, or a similar term, and all salaries are much higher than that.) So I’m not sure exactly what Atlantic and Impulse were offering, but clearly he does not think either one is offering what he’s worth.

He ends with “please do not hold up my Sunday date.” This is a joking reference to “A Monday Date” (aka “Monday Date,” aka ”My Monday Date”), the theme song written by Earl Hines, with whom Mingus had recorded in December 1947. And finally, he sends “Love to all.”

Did this long, rambling letter have an impact? Yes, apparently it did, because, as I noted, around June 1964, Atlantic released the LP Tonight At Noon, comprised of some of the very same tracks that Mingus mentioned in his letter. And he returned to Atlantic from 1973 until his death in 1979.

But most of all, just a week after writing this letter, Mingus held his first recording session for Impulse, a subsidiary of ABC Paramount. On that day, he completed the album entitled The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady (released July 1963) and recorded two pieces that would end up on the album Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus (released January 1964). What was the date of that recording session?

It was January 20—a SUNDAY!

All the best,

Lewis

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.