We continue now with my new series about A Love Supreme. There is quite a bit of new material in these essays, things that I have only recently discovered!

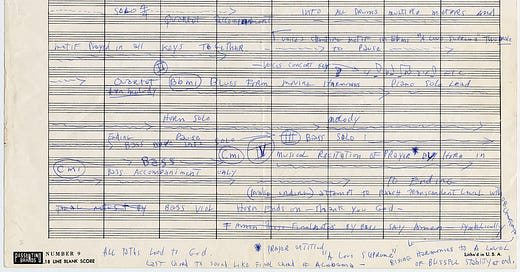

Coltrane’s handwritten plans for the piece appear in Kahn’s books and in some of the album booklets. Page I, the sheet with the most information, is reproduced here. Let’s look closely at this page:

At the very top, Coltrane writes the title of the piece and the instrumentation: tenor saxophone, one other horn, and rhythm section. (He misspells it “rythymn,” which I find endearing, humanizing.) This explains why he re-recorded the first movement with Archie Shepp, added on tenor sax as the “other horn.” For whatever reason, Coltrane always gravitated towards working with another saxophonist — Eric Dolphy, Pharoah Sanders or Shepp — rather than the seemingly obvious choice of a trumpeter. He did once make an offer to Booker Little, according to McCoy Tyner (thank you to Michael Cuscuna for this information). But after Booker died at age 23 in October 1961, John isn’t known to have seriously considered another trumpeter. The late Jimmy Heath once said to me, “As much saxophone as he played, we all thought the Last thing he needed was another saxophone player!” But that’s what John chose.

Also in the top margin, to the right, Coltrane specifies the rhythm section: piano, trap drums (an old phrase for drum set), two bass, two congas, and what looks like “Tymbali.” That could mean Latin timbales, but Elvin plays timpani drums, also spelled “tympani,” on the last movement, and in Spanish “timbali” also means timpani. So, John may have meant timpani but for some reason he was most familiar with the Spanish name for them; or he may indeed have meant timbales but decided to go with the timpani which were already ion the studio. (Thank you to jazz historians Fernando Ortiz de Urbina and Stefano Zenni for discussions of this point.) So in addition to the second wind instrument, he also envisioned an expanded rhythm section. And on the second of two days of recording, he did add Art Davis as a second bassist. All in all, we can say that he had in mind a big sound.

Then he outlines what will happen musically. On the top left, under the name of the piece, he has written “horn opening.” He indicates the notes he will play on the saxophone (aka “horn”), but without rhythms. He then says “Etc.,” meaning that he will improvise on this basis. He writes the concert key, E natural, underneath.

But why does he start in the key of E, if the piece itself was not in E? Wouldn’t it make more sense, for example, to start on the V of the home key? U.K. musician Jacob Egglestone points out (as passed on to me by his teacher Mick Wright) that the pitches that Coltrane writes are the same pitches that “My Favorite Things” begins with, although they are not in the same order. Coltrane writes high C#, low C# (the sharp is understood on this one), F#, G#, and so on. These are in tenor sax key, as we know from the recording—there, we hear the concert pitches high B, low B, E, F#.

Looking again at the “opening,” I now agree that this could indeed be an “homage,” a tribute, to “My Favorite Things.” My reasoning is as follows: Coltrane’s arrangement of that song transformed it into a spiritual experience. He performed that and “Impressions” just about every night, from 1960 until he recorded “Acknowledgement” (and beyond). But, while “Impressions” has a set 32-bar form, “..Things” uses open-ended vamps, with musical cues to say when it’s time to move on. (I’ll investigate that arrangement in another essay.) The first movement of A Love Supreme works similarly. So, Coltrane may be saying that “My Favorite Things” led to A Love Supreme. And he is representing that by having an “opening” in E that leads to the main piece.

He then writes “pause,” and after that the drums come in with the “primary rhythmic motif” (again rhythm is spelled his way), which is the rhythm of the bass vamp. Then he specifies bass and piano in E flat minor, and writes the famous “A Love Supreme Motif” (the Main Motif) in that key. This means that originally, he was going to start in E and then go down a half step.

Instead, he decided to go up a half step to F, which makes it a more positive motion. E becomes a “leading tone” to F. (Here he clearly is not referring to the tenor saxophone keys, because he specifies bass and piano, which are in concert key, and because if he meant the saxophone key of Eb, that would mean a concert key of Db, which is not what he plays.) Between the third and fourth staff from the top, Coltrane writes “melody horn,” which suggests that he might play a specific melody as opposed to an open improvisation. More on this later.

On the next line, he specifies that the saxophone takes his solo in 4/4, accompanied by the quartet. Then he says, “into all drums multiple meters and motif played in all keys together.” It was Joshua Rifkin, one of my mentors, who pointed out to me back in 1979 that at the end of Coltrane’s solo, he was not merely transposing the main motif around, but making a point to go through all 12 keys. I speculated then that this was Coltrane’s way of showing that God is everywhere. Seeing that Coltrane consciously planned that out, by writing “in all keys,” makes me feel even more strongly that my interpretation is correct.

At the end of the seventh staff from the top, Coltrane writes, “Voices chanting motif in Ebmi ‘A Love Supreme’ two male.” Years ago, it was commonly assumed that the two voices were Coltrane and Jimmy Garrison. But it later became clear, by listening closely, that both voices belong to Coltrane. We can now confirm that, as we can hear him overdubbing his own voice on the Complete Masters set. We will listen to that when we start discussing the recording itself.

Next, in the space under the seventh staff, he indicates “To Pause,” getting ready for the next movement. Under this he writes “Voices concert key” and shows the main motif written in F. Now, this is confusing! On this page, not everything is perfectly lined up, so I suppose it’s possible that he meant for the voices to end in F, followed by a pause before the next movement starts in Bb? Another possibility is that he was thinking of the tenor sax key — if everybody else was in Eb, the sax would have been in F (but not the voices).

In any case, it appears that at this point Coltrane did not intend for “Resolution” to be part of the suite. Saxophonist Frank Tiberi recorded Coltrane playing “Resolution” at Pep’s, a celebrated but long-gone Philadelphia club, on September 18, 1964. It’s an amazing 32-minute performance. So he had already composed the piece, but it was not yet included in the suite. Furthermore, “Resolution” on the Pep’s tape is in Bb minor. By the time of the recordings in December, he had added “Resolution,” and had changed the keys around to make it work. If he had left it in Bb, then it would have been in the same key as “Pursuance.” But when he decided to move it to Eb, that would have meant that the entire first side of the LP would have been in Eb minor. His solution (out of a number of possibilities) was to move “Acknowledgement” to F, which as I said creates a more positive motion as well, from the introductory E up to F.

In the middle of the page, marked with a big circled II, Coltrane describes Part II as follows:

Quartet Horn melody Blues form Bb minor Moving harmonies Piano solo lead (as in “piano solo leads off”) Then horn solo— Melody Ending

Clearly, this is what we know as Part III, which makes sense, since he was not yet considering “Resolution.” Although not mentioned in Coltrane’s notes, there’s a long drum solo to kick off this movement. That may have been an impromptu decision in the studio.

In the original plan, the long bass solo was the entire third movement. Coltrane writes, next to a circled III, “Pause. Bass move (sic) into solo. III. Bass solo.” But on the recording it’s a transition between parts III and IV, not a movement in itself.

Just below that, above the fifth line from the bottom, next to the circled IV, Coltrane further notes:

“Cmi (C minor) Musical recitation of prayer * by horn in Cmi.” The asterisk leads to this note on the bottom: “*Prayer entitled A Love Supreme.” To me this is astounding, because it explicitly confirms what I wrote about so many years ago — that in “Psalm” he is “reciting,” syllable by syllable, the poem that he wrote for the album notes! We will talk about this in detail, of course.

Coltrane adds, two lines from the bottom, “Horn ends on Thank you God.” (On the recording it does not end that way— as I’ll explain.) And he crossed off this note on the bottom staff: “Amen — these final notes by bass say Amen symbolically.” To the left of this, he crossed off “final notes by” but left intact the words “bass viol.” It makes sense that he deleted these, because on the recording it’s the sax, not the bass, that says “Amen,” as we’ll see.

There are quite a few remaining notes in the margin at the bottom of this page. For your convenience, here they are, enlarged:

Coltrane writes: “All paths lead to God.” That’s a line from the poem. “Last chord to sound like final chord of ‘Alabama.’ ” Indeed, both pieces use a C minor drone.

Four lines from the bottom, at the top left of this excerpt, he writes, “Bass accompaniment only.” But of course, the recording of the last movement also has the piano and drums (also playing timpani). I suppose Coltrane may have been thinking of starting “Psalm” as a duo with the bass, and then adding the others, because he also writes this, which clearly indicates that everybody is playing at the end:

“To Ending — Make ending — Attempt to reach transcendent level with orchestra — rising harmonies to a level of blissful stability at end.”

He does not mean “orchestra” in the classical sense — rather, that he wants a big, “orchestral” sound. That explains why, though it’s rarely noted, he overdubbed at the end. Yes, Coltrane was not such a purist as one might think, and he was not averse to overdubbing. In fact, he had overdubbed previously on the album with Johnny Hartman (to add some sax fills behind the singer) and would do so again on Living Space in June 1965 (to play the theme on both tenor and soprano sax at the same time).

In the next essay we will hear the overdubbing, and look at some more of Coltrane’s handwritten plans. I’ll see you soon!

All the best,

Lewis

The tidbit about Coltrane's conception of the rhythm section for 'Acknowledgement' has me wondering if the long, loose version of the movement, which includes percussion, from the Seattle performance in 1965 approximates what he initially had in mind.

The spelling of "rhythm" is perhaps poetic? For "Ryt[-]hymn," read "right hymn" or "write hymn."