I’ve said this before, and I’ll say it again: Once people decide that they like an idea, it’s very difficult for most people to change their minds, even when presented with evidence. As the philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote, “People’s opinions are mainly designed to make them feel comfortable; truth, for most people is a secondary consideration.” (From his article “The Art of Rational Conjecture,” 1942.)

It’s clear that many people love the idea that Coltrane wanted to be a saint. I’m going to show that that is a complete misunderstanding of what happened, and that it is also a gross misrepresentation of who he was as a person. And I ask you to please keep an open mind while I explain this:

It all started at the press conference in Tokyo at 1p.m. on July 9, 1966, the first event of Coltrane’s only tour of Japan. (John had arrived the day before, with Pharoah Sanders, Alice McLeod Coltrane, Jimmy Garrison, and Rashied Ali.) In response to one question, Coltrane reportedly said “I would like to be a saint.” This was printed in the Japanese jazz magazine of the day, Swing Journal. (I believe it was the September 1966 issue; the August issue had reviews of the concerts, both positive and negative.) The word soon spread outside Japan. I believe this statement became more widely known in 1975 when it was reported in Chasin’ the Trane, the biography by J. C. Thomas, on page 210.

Immediately, some people latched on to this as proof of Coltrane’s religiosity, and of his own spiritual significance. To this day it is cited again and again, and interpreted very seriously. Most famously, a church in San Francisco is devoted to Coltrane and to what they believe he represents. (Of course, they do not base their practice solely on that one sentence from Japan.)

But for many reasons, the statement never made sense to me. What does that even mean, “I would like to be a saint”? I could not believe that Coltrane meant it in any serious or literal way. I assume that everyone reading this knows that he was deeply interested in spiritual matters—there is no doubt about that, and I’ll even give some evidence below. But announcing that he wanted to be a saint? That would be way out of character. Let me explain:

—Coltrane was a truly humble person. Most people know that one “should” say humble things, but he really was humble, and he always spoke frankly of what he saw as his shortcomings. For example, in 1959, for the liner notes on the back of Giant Steps, the first album made up entirely of his compositions, he told Nat Hentoff, “I'm worried that sometimes what I'm doing sounds like just academic exercises…" This is not how most people sell their album! And part of the purpose of liner notes was to interest people in buying the LP.

When Kitty Grime interviewed him in London in November 1961, he said, “I am quite ashamed of those early records I made with Miles. Why he picked me, I don’t know.” And this was On the record! He told her it was okay to publish it, and she did. Later, in August 1966, Frank Kofsky remarked upon Coltrane’s influence on younger musicians: “I don't see any saxophonist now who isn't playing something that you haven't at least sketched out before." Coltrane denied having an influence. He replied, "No, you know, because like it’s, it’s a big reservoir, man, that we all dip out of.” (This interview is in Chris DeVito’s book of Coltrane interviews, and the audio is here at 29:22.) As I said, he was humble!

—He did not take himself seriously. It wasn’t his nature to say anything that suggested that he was important, or that what he was doing was deeply important. It would be completely out of character for him to essentially “nominate” himself to be a saint. In fact, one could reasonably argue that anyone who would declare that he wanted to be a saint is not suited to be one!

—There is an idea out there that he anticipated his death, and was expressing a wish to be formally sainted after death, as in some Christian traditions. But that can’t be correct, because he no longer followed Christianity. Instead he was developing his own ideas by studying every religious approach that he came across. That’s why there is no mention of saints or Jesus, or Moses or Muhammad for that matter, in A Love Supreme, which is a kind of “interfaith” celebration of God. As he told Hentoff in 1965 for the notes to Meditations, which is essentially a sequel to A Love Supreme, “I believe in all religions.” (A footnote to this: The first movement of Meditations is entitled “The Father and The Son and The Holy Ghost,” which is of course a Christian concept. That was recorded on November 23, 1965. But on October 1, he had recorded Om, which begins with him reading from the Bhagavad- Gita, and on October 14 he recorded Kulu Sé Mama, where Juno Lewis reads his own Afro-Creole prayer. So John was indeed exploring all traditions, not only Christian ones.)

—There is a theory that he was already in pain and therefore knew that he was going to die. But he continued to have a packed performing schedule through the end of 1966. And according to the people who Thomas interviewed, Coltrane only experienced mild headaches in Japan. Nobody who knew him noticed anything unusual, or heard him express any serious discomfort, until around March 1967.

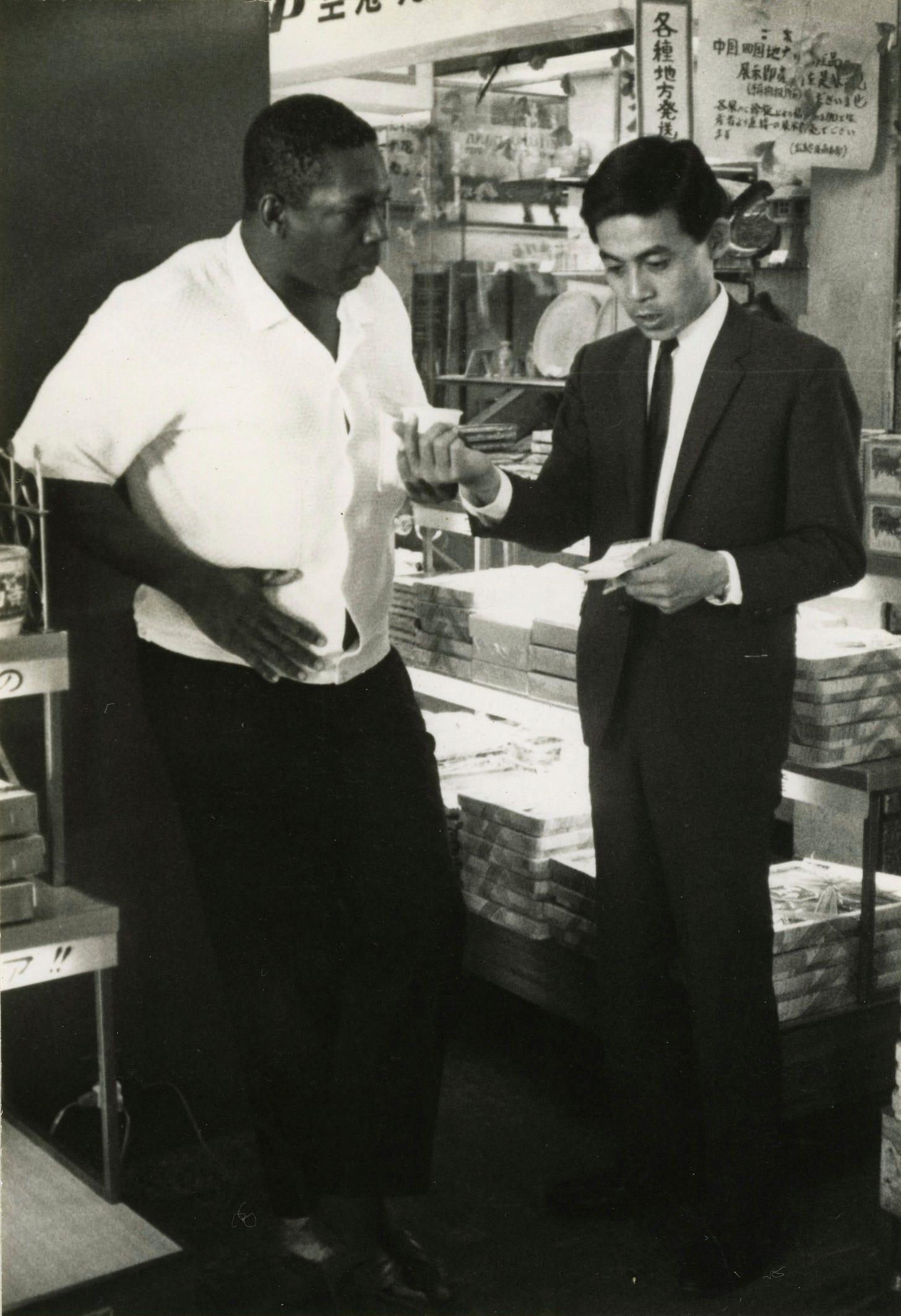

What about Rashied Ali’s observation that, when he later reviewed photographs from Japan, he noticed that John appeared to be holding his stomach in pain? Well, the photos do not show that. Coltrane tended to rest his right hand on his side when he was standing around. Here is one of the photos in question (courtesy of my friend and coauthor of the Coltrane reference book, jazz journalist and discographer Yasuhiro “Fuji” Fujioka; also printed in the Coltrane biography by Simpkins, published in 1975). The other man is Ennosuke Saito, the road manager for the tour, and he’s going over some details. John is listening to what Mr. Saito is saying, and there is no reason to think that he is in pain:

Even biographer J. C. Thomas disparaged the attitude that Coltrane was setting himself up to be some kind of religious figure, or that he should be treated as an icon. At the end of his book, he wrote (pages 228-9):

I do not agree; I cannot agree. Trane and Buddha, both great teachers in their differing styles and different times, suffered from similar misconceptions by far too many of their followers. While alive, they were addressed as gods; when dead, they were worshiped as God. They received not genuine respect but mindless adoration.

But the most important piece of evidence is that, after many years, my colleague Fuji, whom I just mentioned, discovered that someone had recorded the press conference! We can hear it! Many of the questions at the event came from Kiyoshi Koyama (1936-2019), who wrote for Swing Journal and would become the editor in 1967. Some questions also came from one of the first Japanese jazz critics, Shoichi Yui (1918-1998). The questions were translated to English by Ennosuke Saito, so you will hear his voice. Thanks to Fuji, the full spoken exchange was included in a 5-CD set entitled Concert in Japan/Deluxe Edition (also streaming on Spotify et al). First, let’s listen, and then I’ll show it to you as text:

Here is the transcription by Chris DeVito (lightly edited by me), from his book of Coltrane interviews:

Coltrane: Could someone else answer some questions too? Could some of the other members of the group answer questions?

Saito: OK—The gentleman [Koyama] apologizes that he has been repeating (sic) asking questions for you alone, but now, as his final question, he wants to know, what, or—and how, you would like to be in ten or twenty years later. How you—you would like to be, well, in what kind of situation, you would like to, uh, establish?

Coltrane: As a musician, or what, as a person? Or—

Saito: Let’s say about—as a person.

Coltrane: In music, or—As a person. [3-second pause] I’d like to be a saint. [John chuckles, followed immediately by Alice]

Saito: You’d like to be a saint, huh? [More laughter from John and Alice]

Coltrane: Definitely.

What?! It wasn’t a serious comment after all! John and Alice laughed!

So now the question is, What was the joke? Why was it funny? To understand this, you have to know that John’s friend Sonny Rollins toured Japan for the first time three years earlier. He too had a press conference, on September 19, 1963. Rollins said that he hoped to learn about Zen Buddhism while in Japan. The next exchange was as follows, as reported in DownBeat (December 19, 1963, p.16):

The concept of a saint in Buddhism is different from the Catholic concept. This is from Wikipedia: “…People who are considered saints in Buddhism are sages who became fully enlightened and are renowned for their holiness and compassion.”

(Paying Subscribers, scroll down for the full-page report of the Rollins conference.)

Now we know why Coltrane said it in 1966—and now we know why it was funny and made himself and Alice laugh! John was referring back to Sonny’s statement. When John added “Definitely!,” that was just his way of saying “Get it?,” of adding some emphasis.

Coltrane knew that Sonny had said that in 1963. Probably he saw it in DownBeat, which many jazz musicians read regularly, and probably he even talked with Sonny about it. Coltrane, being the kind of person that he was, probably would have thought that Sonny’s comment came off as self-important, and he may even have teased Sonny about it. (I can imagine him saying to Sonny, “So you want to be a saint, huh?” Or “Hello there, Mister Saint!”) Alice and John had been together since July 1963, when they met while performing with different groups at Birdland. (In those days clubs usually had two groups alternating every night.) So she also knew about Sonny’s statement, and how John felt about it.

The members of the Japanese press knew about Sonny’s comment as well. There were reportedly about 450 journalists at the 1963 event, so there were probably a comparable number at Coltrane’s conference. Many of the same people attended both events. It’s even possible that Koyama’s somewhat vaguely worded question was an attempt to get at something like what Rollins had said, to get Coltrane’s take on what or who he’d like to be in the future. Coltrane understood that, and he responded accordingly, with humor. Even the way that he says it—”I’d like to be a saint”—is informal, not the way it has been reported. It is usually written as “I would like…,” which sounds more like a formal announcement.

Coltrane’s reply was a comment, a “riff” (a “signifier,” if you prefer), on what Rollins had said to some of the same press members three years earlier. Comedians refer to this as a “callback,” when you refer back to something that you or someone else said earlier. And cellist Travis Scharer, one of my graduate students at New England Conservatory, also noted that the exchange begins with Coltrane suggesting that the other musicians could answer some questions. He’s ready to move on. This was not his moment to make big pronouncements.

When I’ve explained this, some people have said to me, “Okay, I hear him laughing. But maybe he was just nervous. It doesn’t mean he wasn’t serious.” I’m sorry, but that is precisely what it does mean—that he wasn’t serious. Listen again—does he sound nervous to you? And remember, not only he laughed, but Alice did too. How would you explain that? The only explanation is that it was funny to them both! Even Saito’s response sounds as though he might have understood that it was said in jest.

Others say to me, “Okay, I understand now that it was a joke. But don’t all jokes contain a kernel of truth?” Yes, but in this case the kernel of truth was “Sonny expressed this self-important goal when he was in Japan, so I’m making a joke about it, to kind of deflate that importance in a way, to bring it, and myself, down to earth.” The kernel was absolutely not “I am a deeply spiritual person and I hope you realize how important I am, and please take my statement very seriously. I am working toward an elevated and saintly state of being.” No way!

He never took himself seriously—certainly not as seriously as everyone else seems to take him! Remember, this is the same Coltrane who, about nine months earlier (October 2, 1965) in Seattle, took his “holy, sacred, important” piece (in the words of others, not Coltrane) A Love Supreme, and turned it into a loose jam session with guest musicians, some of whom were not even familiar with the piece. At the end, guest bassist Donald Rafael Garrett continues playing after everyone else has stopped. Then he looks at Coltrane and asks “Is that it?,” and Coltrane replies, humorously and light-heartedly, “It better be! It better be, baby! Yeah!”

This is not a person who would say, in any serious manner, “I want to be a saint” or “I would like to be a saint.” Of course, you can and should believe whatever you want to believe, about Coltrane or anything else. And you can honor Coltrane in any way that you wish to. He deserves it—he was not only an amazing musician, but by all accounts he was a wonderful person. And it would be truly nuts to doubt that he was deeply interested in spiritual matters. He made many public statements about these interests, and he recorded music inspired by his spiritual studies. ALL I am saying is:

Please don’t believe that Coltrane wanted to be a saint, in any sense of the word.

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Paying subscribers, as usual your gift is below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.