In the career of any artist, there are always many projects that are proposed, and many of these never happened. In this series I’ll share with you a few ideas that would have involved John Coltrane, but that never took place.

Tom Wilson (1931-1978) was a visionary record producer with incredibly broad interests and experience. A Black man born in Waco, Texas, he attended college at Fisk and Harvard, then stayed in Boston and founded the Transition record label that released Cecil Taylor’s first album, recorded in 1956, as well as albums by Sun Ra, Herb Pomeroy, Pepper Adams, Donald Byrd, and others. But Transition went out of business the next year, 1957, and Wilson sold his recordings to other labels. Then he produced albums for United Artists, including the famous Cecil Taylor album with Coltrane and Kenny Dorham, and stayed there through about May 1959. By late August 1959 he was producing for Savoy Records, and by early 1963 for Dauntless. In April 1963 he joined Columbia Records as a staff producer on salary (the first black person to hold that position). He famously worked with Bob Dylan on some important early recordings, and went on to produce for Simon and Garfunkel, and, after Columbia, for Frank Zappa, the Velvet Underground and others.

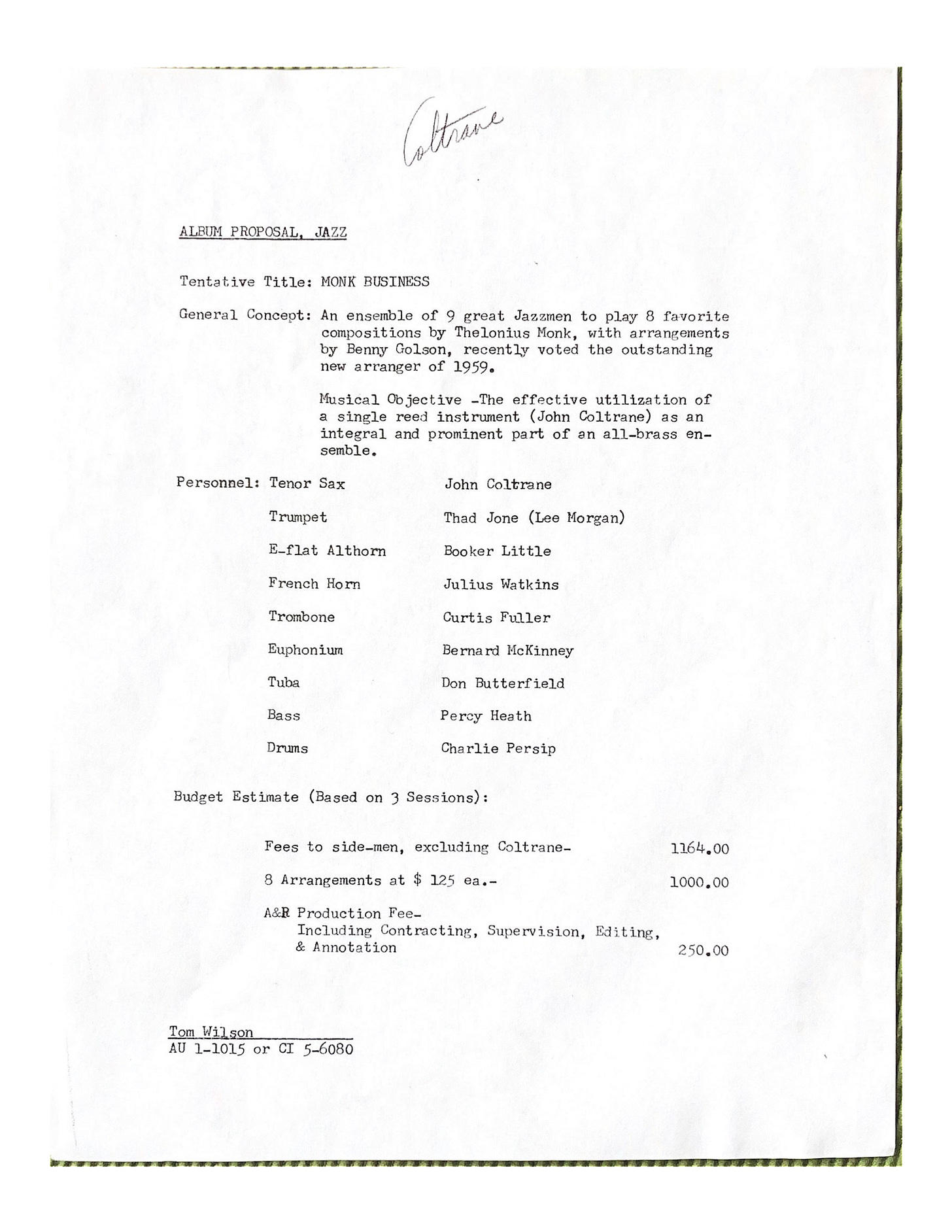

In this brief summary of his career, you might notice that there is a gap in the summer of 1959. Most likely, it was during that time that he sent a written proposal to Atlantic Records. And what a proposal! Take a look:

Starting at the top, the handwritten word “Coltrane” was not on the original letter. It was added at some later date, maybe many years later, simply to indicate that this should be filed under his name.

Without a doubt, Wilson had discussed this with Golson before writing up the proposal: “What do you think of this idea? Would you be OK with this fee?” Golson and Coltrane were the two essential people in this project. Everybody else could be replaced if necessary. It would make no sense to ask Atlantic for Coltrane’s participation if he didn’t already have Golson’s approval.

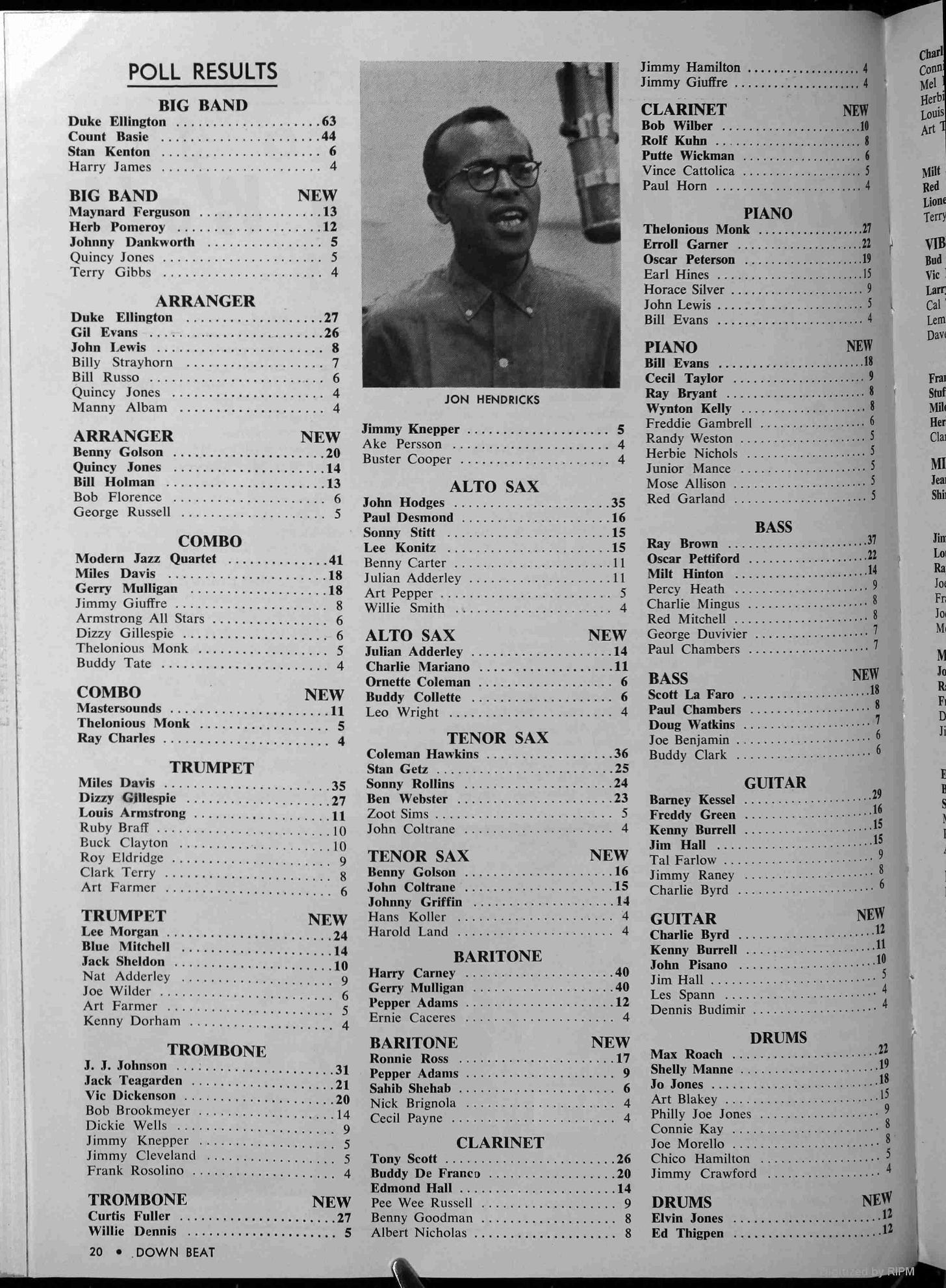

The page has no date. (There was probably a cover letter to Nesuhi Ertegun, now lost, that had a date. Or maybe Wilson phoned, and Ertegun said “Please write a proposal and send it over so I can look at it.”) But we can figure out an approximate date because he refers to the fact that Benny Golson was “recently voted the outstanding new arranger of 1959.” This refers to the 1959 Downbeat Critics’ Poll. In each category, there was a winner among established musicians and another in “new” musicians. Duke Ellington won in the “established” arranger category, with just one more vote than Gil Evans. Golson also won in the “new tenor sax” category, with just one more vote than—guess who?—Coltrane! Here is the relevant page:

This appeared in the Downbeat issue dated August 6, 1959, which was published about a week before that date. On August 25, Wilson produced his first recording session for Savoy, so I would say that most likely he sent this letter in, let’s say, early to mid-August. However, it is also possible that he wrote this after August 25, but not much later, because of that word “recent.” He may have proposed it first to Savoy, but if so, he was probably told that, although Coltrane had recorded for them when he was with Prestige (as a sideperson to Wilbur Harden), they couldn’t afford Coltrane now that he was an Atlantic Records artist.

On the other hand, Coltrane was obligated to record a certain number of albums per year (probably two or three) for Atlantic. So, if Wilson could get them to agree that this would count as one of his Atlantic albums for that year, they would pay Coltrane for it. That’s why he doesn’t include Coltrane in his budget.

As for the other fees, these were determined by the “scale” (standard minimum rate) set by the musicians’ union (the N.Y.C. Local 802 of the A.F.M). The union was involved in professional recordings—paperwork was filed through the union, payments were made by the record company to the union, and the musicians went to the union to pick up their checks, from which dues and any other fees were deducted. A recording session was always three hours and musicians were paid $48.50, which comes to $16.17 per hour. And if it went past three hours, they were paid extra. The leader was usually paid double, but also received royalties, and an advance credited against future royalties. (Sidepersons never received royalties—they did “work for hire.”) Wilson was planning on three recording sessions (three hours each), and if you do the arithmetic, you’ll see that his figure of $1164 is indeed three times $48.50 times 8, for the eight band members.

Wilson’s personal fee of $250 seems to be reasonable, considering that it includes:

Contracting (contacting the musicians and setting dates)

Supervision (being at the recording sessions, as a producer should be)

Editing (sitting with the engineer after everything is recorded, to decide what has to be edited, how the sound could be improved, etc.)

Annotation (writing the liner notes). Wilson had written notes for the backs of several of the albums he produced. If they hired someone else to write them, that person would have had to be paid and that fee would have added to the cost.

The proposal shows that Wilson knew the jazz scene very well. It’s not a random group of musicians and tunes, but a thoughtful combination of players. Although he had only been producing records for about five years, he had already worked with a great variety of players, including most of the ones he named. The fact that he lists Booker Little on Eb althorn (a brass instrument also known as alto horn and, confusingly, as tenor horn) shows that he knew Booker personally. No producer would list someone playing such an instrument, rarely found in jazz, unless they knew that person could play it. (Also, Thad Jones’s last name is misspelled—just a typo.)

The goal, as stated, is to feature “a single reed instrument (John Coltrane)” with an “all-brass ensemble.” Notice that there is no piano. Wilson is clearly looking for a very particular sound.

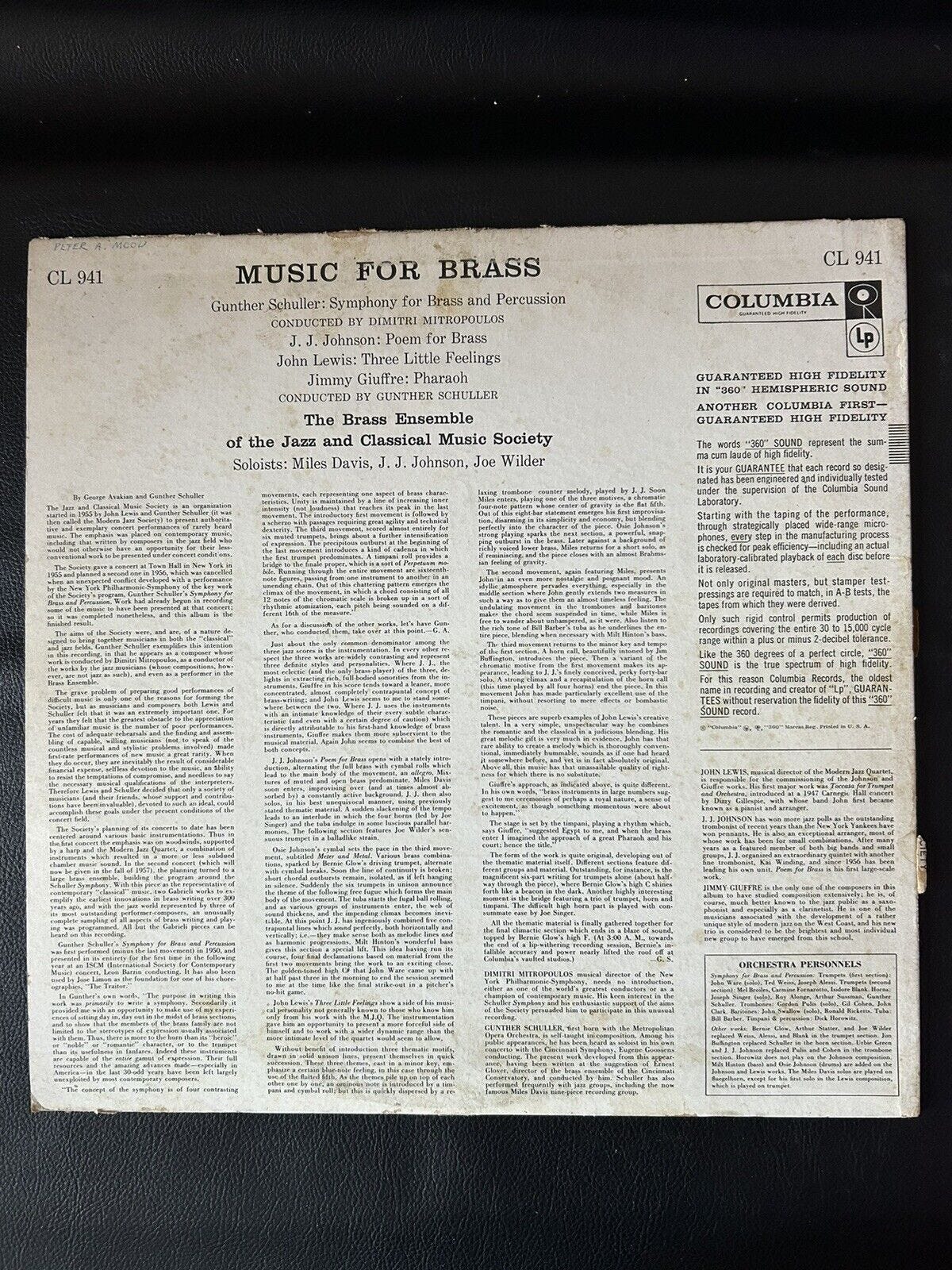

But WAIT a minute! This proposal is starting to sound very familiar. In October 1956, Gunther Schuller conducted the Music For Brass album for Columbia Records, which featured Miles Davis and J.J. Johnson soloing on compositions for sixteen brass instruments plus bass and drums, and with no piano. That’s twice as many brass players, but the idea is the same (personnel list is at the bottom right):

And of course, in 1957 and ‘58, Miles had recorded two very successful albums accompanied by the brass-heavy big band sounds of Gil Evans. (Thank you to subscriber Chuck for making this connection.) And in July 1958, just before Wilson sent his proposal, the album Sonny Rollins and the Big Brass was produced by Leonard Feather, but the title is misleading because there are only four short large group tracks, out of eight. But those tracks do indeed feature eight brass musicians plus rhythm section, in this case with both piano and guitar. Ernie Wilkins wrote the arrangements. That might not have been released yet, but Wilson might have known about it. (Thank you to subscriber DJPeter DE for this one.)

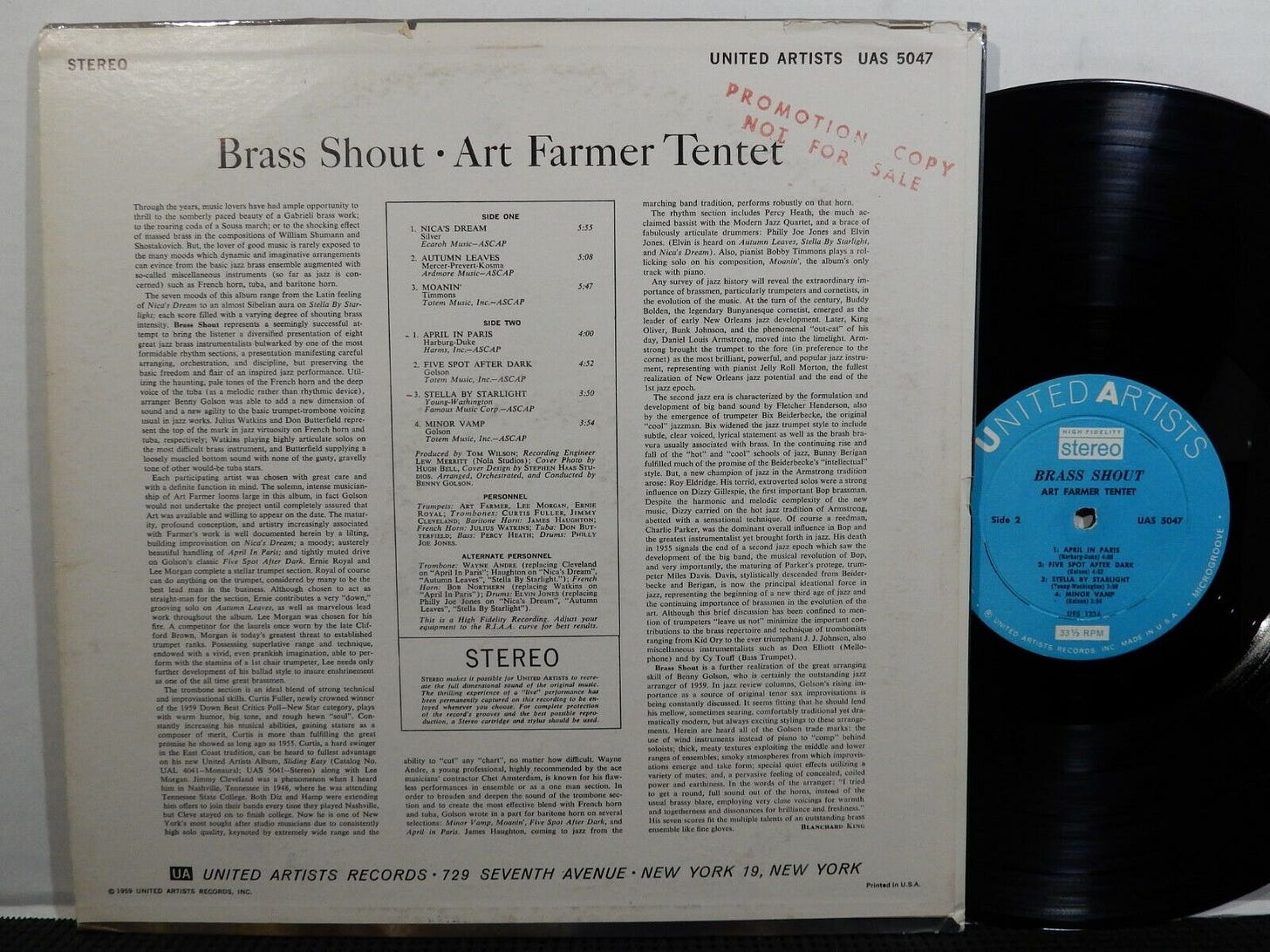

But the most relevant predecessor of all, recorded just a few months earlier, in May 1959, is an Art Farmer album entitled Brass Shout, which Wilson himself had produced for United Artists. The concept was the same as he proposed for Coltrane: To feature a single soloist—in this case Farmer—with an ensemble of eight brass players, plus bass and drums and no piano. (Actually, pianist Bobby Timmons is the guest soloist on his own tune “Moanin’,” but he doesn’t even back up the other soloists, in order to stay with the tone of the album.) And four of the players on the Farmer album were the same ones that Wilson proposed for Coltrane—Watkins, Fuller, Butterfield, and Heath. And the arranger? Golson, of course. Here’s the album back:

The Farmer album was released around Thanksgiving 1959. I’m sure that Wilson told about Ertegun about the forthcoming album, and proposed that the album with Coltrane would make a great complement to the Farmer album—and that featuring the music of Monk, with whom Coltrane had created a sensation in 1957, would attract a lot of buyers. (The Farmer album was recorded in one day, but WIlson asked for three days for his Coltrane project. Probably he had learned from the Farmer album that a larger group like this, with lots of writing by Golson, ideally required more time to get everything just right.)

Why was his proposal rejected? There could have been many reasons. Coltrane had recently recorded Giant Steps, the first album made entirely of his own compositions. Why should he go back now to recording other peoples’ songs, even great ones like Monk’s? The plan, looking ahead, was to feature Coltrane on his own music, and eventually with his own band. (Giant Steps was not released until February 1960, so Wilson would not have known about it.)

Furthermore, Monk was not an Atlantic artist. (In 1958, he had recorded for them with Blakey, but only as a “special guest.”) How did it benefit Atlantic to promote Monk’s music, and to pay the costs, including composer’s royalties to Monk?

There may have been other reasons that it never happened. But, if it had happened, I would have bought it! Probably you would have as well.

Oh, well. Here is the opening track from the Art Farmer album—imagine a Coltrane solo in there. It’s fun to think about it. And subscriber Michael Farina makes the point that perhaps this idea of Coltrane and brass didn’t die after all. It might have helped to inspire Coltrane’s Africa/Brass album, recorded in May 1961. The French horn section on that album makes it a very different group, plus there’s Tyner’s piano. But the point still holds—it’s like Wilson’s idea, mostly brass, but featuring Trane’s tunes and his group concept, which is what Coltrane was after (and I assume his producers were as well).

More to come!

All the best,

Lewis

This is fascinating stuff! While I’m bummed this never happened, I can’t help but note the similarity in concept and instrumentation to Africa/Brass which also winds up with the theme of Coltrane (and in that case his quartet) placed in front of a band with a largely brass sound. I wonder if we got this album if Coltrane would go on to record Africa/Brass at all, or if it’d be wildly different from the way we know it. With the pianoless vibe of this suggested group, I’d imagine the album we could have gotten would have been a strange mix between Africa/Brass and The Avant Garde. I wonder if Coltrane and Don Cherry recording Bemsha Swing for that album is just a coincidence given the fact that it stands out so strongly being placed with what is otherwise exclusively Ornette’s repertoire. Maybe it was a reference to this failed project? I also wonder if Coltrane’s dental work that he had in ‘59 (if I remember correctly) could have been another factor in the cancellation of this project. Either way thanks for sharing this amazing stuff as always!

Didn't Sonny Rollins also do an album with brass? (Checks: ah, recorded July 11, 1958 for Metrojazz, tuba but no french horn, and with piano and guitar; Ernie Wilkins charts.) More conventional big band approach (if memory serves, and it doesn't always), so maybe not in the lineage you're sketching out here.