Coltrane: The Origin of "Impressions," Part 3--with Bonus Audio for Paying Subscribers

Why he used Ravel for the bridge, and why he chose the name "Impressions."

(Paying subscribers, in conducting this research I came across some very enjoyable versions of Gould’s “Pavanne.” They’re not essential to my Coltrane research, so I’ve included them at the end of this post, as another THANK YOU for your support.)

Let’s check out some more of my NEW RESEARCH on Coltrane!:

I ended Part 2 with several open questions. Let’s address this one first: Why did Trane decide to use “The Lamp Is Low” as his B section? That choice appears to be kind of random, doesn’t it? Why not just keep doing what he did at first, which was to play the Gould theme up a half-step? Or, why not compose an original bridge, as is usual? Or, if he wanted to use a pre-existing song, why not choose any of a million other songs to use for the bridge? After all, “The Lamp is Low” was a very slow vocal number, not at all obvious for the bridge of a fast, swinging tune.

Well, as you now know, his A section came from Morton Gould’s “Pavanne.” So I tried to reconstruct how he decided to use another “Pavane”—Ravel’s, spelled differently--for the bridge. As part of my research for this series, I tracked down and listened to just about every jazz recording entitled “Pavanne” or “Pavane” through March 1961. (Remember, Trane started playing what he later called “Impressions” in 1960, and he added the Ravel bridge by or before March 1961.) For the spelling “Pavane,” there were just four versions during those years, and all were arrangements of Gould’s piece, even though Gould preferred two “n’”s.

It seems that Gould inadvertently created a permanent mess by spelling his piece with two “n’”s. That’s why I had to check pieces spelled both ways. We’ll never know why he insisted on spelling it that way. Perhaps he simply hoped to keep it from being confused with Ravel’s famous “Pavane Pour Une Infante Défunte”? If so, that didn’t work. Instead, people started spelling Ravel’s piece with two “n’”s, Gould’s piece with one “n,” etc.!

Moving on to the spelling “Pavanne,” all of the early ones from 1938 through 1944, were, as might be expected, arrangements of the Gould piece—such as the ones you heard in Part 1 performed by Lunceford, Miller, and Gould himself. After 1944 there’s nothing, until this one recorded in New York, July 20, 1949:

“Pavanne,” Erroll Garner Trio : Erroll Garner (p) Leonard Gaskin (b) Charlie Smith (d)

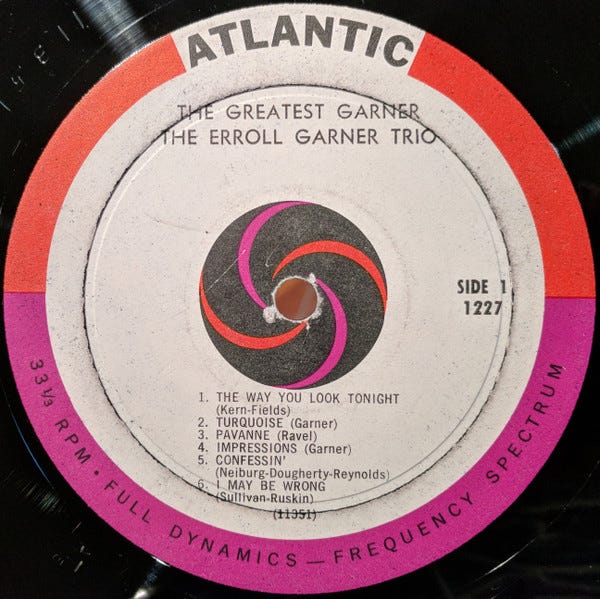

This was the first instrumental version of “A Lamp Is Low.” Significantly, it was also the first swing version, as opposed to the leisurely “ballad” tempo of the vocal versions such as Mildred Bailey’s (which we heard in Part 2). In fact, when it was released on LP in 1950, Leonard Feather, in his liner note, specifically described this as an “unusual treatment.” So, upon hearing this, it would have been easier for Trane to envision it as the bridge of a fast piece. But equally important, it was not titled “The Lamp is Low,” nor “Pavane Pour Une Infante Défunte.” Nope—it was called simply “Pavanne,” just like Gould’s piece. Check out the label of the 78rpm recording!:

(The other side of the 78 was the old Count Basie ballad “Blue and Sentimental.”)

The truth is, Garner plays “The Lamp is Low,” which has an AABA form and a bridge that are not part of Ravel’s original piece. That makes it all the more interesting that it’s called “Pavanne” and credited to Ravel, a choice that could have been made by the producer, not necessarily by Garner. Let’s give it a listen:

Now, John and Erroll knew each other. In February 1947, John had met Garner, who was already a rising star, when Erroll recorded with Charlie Parker in Los Angeles. John was on tour there with the band of now-forgotten trumpeter King Kolax. According to singer Earl Coleman, who was also on the recording session, Coltrane was present in the studio and stayed around to jam with them all afterward. Further, the Miles Davis Quintet with Coltrane played on the same bill as Garner in November 1955, and they were appearing in the same city in 1956 and at other times. By the late 1950s, Garner was one of the most popular artists in jazz, on the level of Duke, Louis, Miles, Shearing, Jamal, Brubeck, and very few others.

I can’t help thinking that seeing a piece by the acclaimed Garner entitled “Pavanne” attracted Trane’s attention, and that when he heard it, he began to consider this for his bridge. But there’s an even more compelling reason to think so—stay with me:

After Garner’s recording, medium-tempo and even fast instrumental versions of the Ravel theme became commonplace, but all under the name “The Lamp Is Low.” (Before Garner, all versions called “The Lamp is Low” were vocals.) There was Chet Baker’s fast version in 1953 (at a tempo of about 226 beats per minute), Don Elliott in 1955 (ca.160 bpm), and Marty Paich in 1956 (ca.220 bpm). Also in 1956, both Johnny Hartman and Donna Brooks made vocal versions that were faster than Mildred Bailey’s. And that same year, alto saxophonist Bud Shank recorded an arrangement that starts slow but then suddenly gets very fast (ca.310 bpm).

Maynard Ferguson’s 13-member band recorded a swinging version in July 1957 (ca.176 bpm) , and in August 1958, so did bass trumpeter (sic!) Cy Touff (ca.210 bpm). Even an all-star band of fine Swing Era musicians led by trombonist Vic Dickenson recorded it as a swing number in 1958, but at a more moderate tempo (ca.144 bpm).

(For research like this, the best resource is The Jazz Discography at Lordisco.com, a database of all known jazz recordings from the early 1900s until now. It’s maintained and regularly updated by Tom Lord, who lives near Vancouver, Canada. One can search by tune title, musician, band name, any combination of the above, and more. Access is $10 a month, and one can cancel at any time.)

So, by 1960 or ‘61, John had many precedents in using Ravel’s theme as an uptempo piece. (His Vanguard version clocks in at about 260 bpm.) Surely he would have heard some of these. Maynard Ferguson’s band, for example, kept “Lamp” in their “book” (their repertoire) at least through June 30, 1960, when they performed it at Newport. And the Miles Davis group with Coltrane played on the same bill with Ferguson’s band, alternating sets at New York’s Birdland, in January 1959 and again in September-October 1959. And those were the days when Maynard led a hard-core jazz band featuring such musicians as Wayne Shorter, Joe Farrell, Jaki Byard, Slide Hampton, and others! It would have been difficult for John not to have heard their version of “The Lamp is Low”!

And don’t forget that Chet Baker was one of the most popular artists in ‘50s jazz, so it’s also very likely that Coltrane heard his version. And guess what? We talked in Part 2 about the slight change that Trane made in the melody by playing Gb (instead of F) as the fourth note. Chet did that on his 1953 recording! The swing all-stars group also plays the Gb, and I wouldn’t say that Coltrane necessarily heard that recording, but that supports my point that it’s natural to change that note when swinging the piece.

Also, many fans have pointed out that Coltrane was fond of puns, and titles with multiple meanings. So it stands to reason that, having taken his A theme from Gould’s “Pavanne,” he would have been delighted to take the theme for the bridge from yet another “Pavane,” the one by Ravel, especially if spelled “Pavanne” on a recording by such a noted artist as Erroll Garner.

But, now that he’d assembled his piece, and chosen his bridge, what about the name for it? I believe that one reason he had such difficulty naming it is that he had taken themes from Gould and Ravel and placed them over a form by Miles Davis. Although he was not overly shy about taking credit—as I showed, he claimed “Spiritual,” even though he’d gotten it from a book of public domain songs—it would be a bit much to claim this particular song as his own, when Gould and Miles were still very much alive, as were two of the authors of “The Lamp Is Low” (Peter De Rose had passed away in 1953). And all of their works were still under copyright! I’m sure that he wondered, “Can I ethically justify taking the credit for this piece, or even legally do so?”

On the other hand, he had to credit it to somebody (it certainly wasn’t public domain!), and he knew that it would have made no sense to credit it to Morton Gould, Miles Davis, and Maurice Ravel (not to mention the authors of “Lamp”). Composer listings like that are only used when the musicians have actually collaborated on a piece, and it would imply that all of them had sat down and worked together on this, which was of course crazy to suggest (not to mention that Ravel had died in 1937).

Nevertheless, as I will explain in detail in a separate post at some point, when one was under contract to a record company, there was in general a pressure to come up with original pieces. It was better for the label to record new pieces by their artist (no fees would be owed to Davis or Gould or others), and better for the artist (he or she would collect composer royalties—in addition to the mechanical royalties for LP sales, which are a given). So there was some pressure, gentle or not, for John to come up with a name and to call it his original composition.

So, why “Impressions”? Let’s go back to Garner’s “Pavanne,” but this time let’s look at the LP releases of this recording. You already saw the label of the 78 rpm release above. But “Pavane” was also released on Atlantic LPs, in 1950 and in 1956. Here are the labels of both LPs, that is, the side of each LP that contained “Pavanne”:

Holy Moly!! OMG!! In both cases “Pavanne” is followed immediately by “Impressions”! Do you really think there is any way that Trane did not notice that?

In fact, there is a very high chance that Coltrane saw one or both of these Atlantic LPs. Remember, at the time that he started performing what he later called “Impressions” he was recording for Atlantic! (His Atlantic contract lasted until the end of April 8, 1961, and his first recording for Impulse was in May 1961.) When one records for a label, one has easy access to other recordings from that label. To this day, it’s easy to say “Hey, could you send me some of those albums you put out by so-and-so?” It was even easier in those days, when Atlantic’s offices were in the middle of Manhattan. (They were on West 56th street at the time of the first LP, and on West 57th St. at the time of the second.) In fact, when Coltrane was at the Atlantic offices for some other reason, he could just ask to take a few LPs home. And these were Atlantic’s only Erroll Garner albums (both contained the same 10 pieces, and the later one had 2 additional ones), so one couldn’t miss it. (In his early days Garner recorded for many different labels, before signing with Columbia.)

But wait—there’s more! What was the music on Garner’s “Impressions”? It’s Garner’s improvisation on Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” (in English, “Light of the Moon,” better known as “Moonlight”). Debussy’s theme is clearly stated at the outset, but Garner improvises freely, and it’s credited to Garner on the labels (whereas “Pavanne” is credited to Ravel). Maybe this was the example that John needed to see, that told him that it was OK for him to claim the credit for the piece he put together from “excerpts” of Gould, Miles, and Ravel! After all, with any performance of Coltrane’s piece, by far the main part was John’s improvisation, which was as free as anything could be.

I wouldn’t be surprised if he talked with Miles as well, and I’m sure Miles would have said “You’re not using the theme of ‘So What,’ only the form, so don’t worry about it.”

There used to be an idea circulating that the title “Impressions” came to Coltrane because the A section was from Debussy (it’s not of course), and since the B is from Ravel, both themes are by “impressionist” composers. But as I’ve shown, the first theme is by Gould, not Debussy.

No, that has nothing to do with it: The title “Impressions” was inspired by Erroll Garner’s “Impressions,” I believe!

(By the way, on its first release, which was on 78 rpm in 1949, Garner’s “Impressions” was backed by Debussy’s “Reverie.” So both sides of that 78 were by Debussy, but of course “Impressions” was credited to Garner. Both were recorded on the same day as “Pavanne.” I guess Erroll was the one who was into “impressionist” composers.)

In the next part, I’ll show how and why, before Coltrane’s own version was ever available, his “Impressions” became known to other bands, and even got recorded and released by two of them. And we’ll discuss some interesting questions about how to improvise over Coltrane’s “Impressions.” I might choose to post one of my many other research projects first—but in any case I’ll see you again soon!

All the best,

Lewis

PAYING SUBSCRIBERS—Please scroll down for three very enjoyable versions of Gould’s “Pavanne”!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.