Dan Morgenstern (1929-2024) was one of the best-loved jazz historians and journalists. I knew Dan professionally for many years, and when he died, I posted a short essay about him with a surprise film clip. And I will be sharing my personal memories of him now and then. But today, I want to present some information from my research into his family history. This could easily take up many essays, so I’m just going to focus on a few matters that I believe you will find fascinating.

When I first met Dan around 1978, he never talked about his personal story as a Jew in Europe during the Nazi era. He had no discernible accent, and many did not even know about his background. But as time went on, he opened up about that and provided many details, for example when he was interviewed by his late friend and colleague Ed Berger for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program (JOHP; a transcript and a few audio excerpts are at this link).

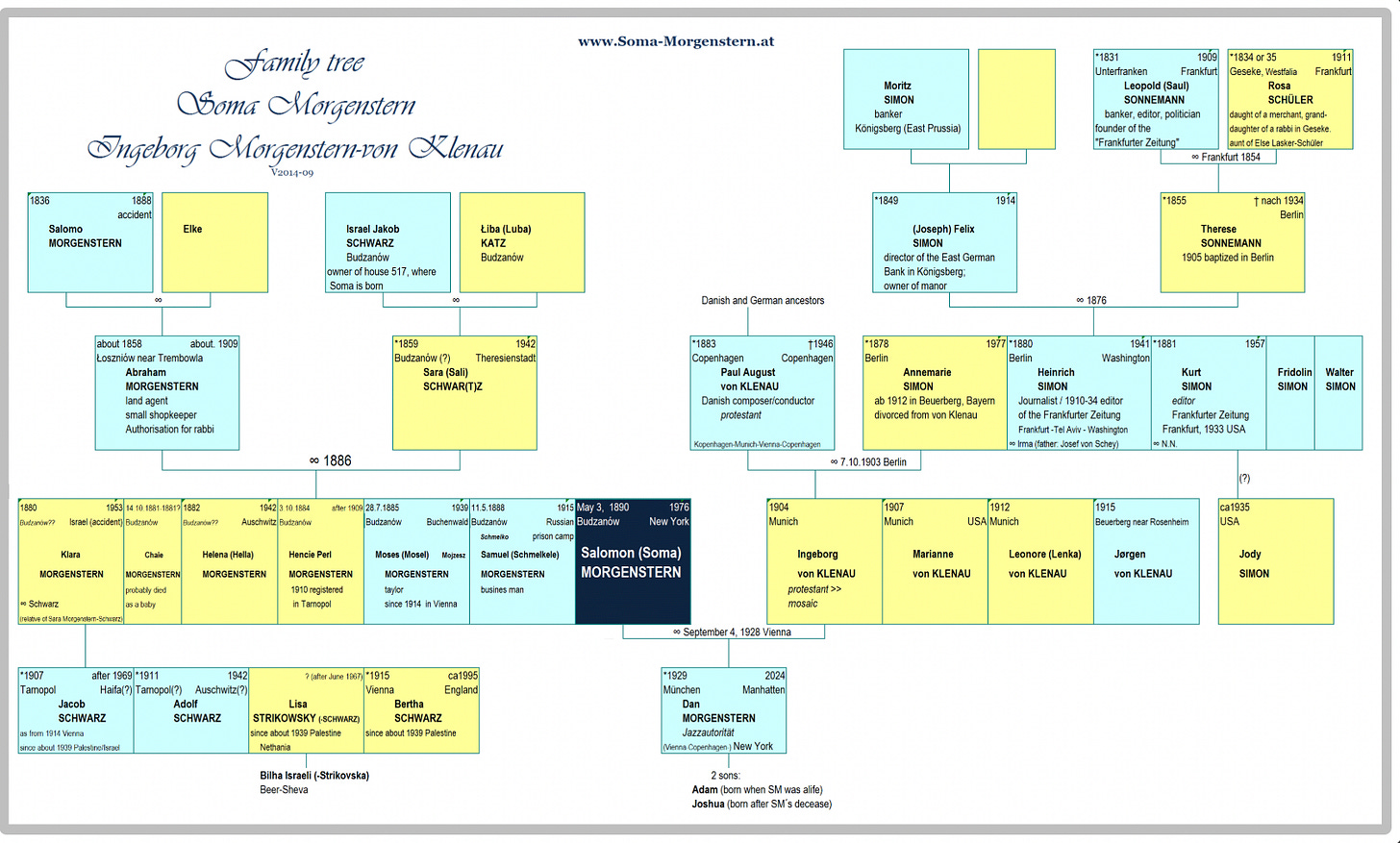

I’ve delved into his family recently and come up with quite a bit more. First, let’s look at his family tree, from an extensive site devoted to his accomplished father, the fiction and essay writer Salomo “Soma” Morgenstern (1890-1976). Below you will also find his name spelled as “Salomon.” It’s a variant of “Solomon” in English and spelled differently in different languages, but all versions are related to the Hebrew word “Shalom,” meaning “peace.” This tree goes back to around 1830. (In my own research, I have extended some lines back to about 1800.) You might want to enlarge this in order to read it more easily:

To the left of Dan’s father Soma, who is highlighted in the black box, are Soma’s siblings. It shows that three of them, Dan’s aunt and uncle and paternal grandmother, were murdered during the Holocaust. According to Dan’s JOHP interview, Soma never got over that.

Dan’s mother, Ingeborg “Inge” von Klenau (1904-1992), was about 14 years younger than Soma. She had three siblings, and you will notice that in the tree it says “Protestant” next to her name and that of her father, the composer Paul von Klenau. More specifically, they were Lutheran. So Dan had one Christian grandparent, making him three-fourths Jewish. In the family tree, the von Klenau line of his mother’s father is not traced back. But it’s an amazing one, so let me tell you just a little about it:

The von Klenaus are an old German family—they can be traced as far back as the 1400s, at least. They came to Denmark in the early 1500s—some sources say that happened later, around 1700, with the arrival of Christopher von Klenow (sic) in Denmark. Dan remembered in his JOHP interview that “there was a general” in their lineage. That general was Johann von Klenau (1758-1819), who led soldiers in many important battles, including against Napoleon! (The Wikipedia entry on Johann also gives some overall history of the von Klenau family.) There was also another musician in the family lineage: Paul’s mother was Ingeborg Birgitte Berggreen, a descendant of the Danish composer Andreas Peter Berggreen. Probably Dan’s mother Ingeborg was named after her.

So, let’s find out some more about Dan’s maternal grandfather, Paul August von Klenau (1883-1946). (His first name was not Karl—that is an error in the JOHP transcript). Dan talked a little about him in the JOHP Interview:

My mother was born in Germany. Her father was Danish. He was a composer and conductor…He was a baron [Lew notes: as were many of the von Klenau men historically], but he didn’t use the title. He was a modestly gifted composer, but very prolific, who wrote a number of operas.

But actually there was more to Paul’s music than that. If you search any of the streaming services or YouTube you will find that in recent years there have been many recordings of his instrumental music—symphonies, string quartets, and more. Considering that Paul was the same age as Stravinsky, his music is conservative for the time, but it’s well-crafted and very melodic. I like his violin concerto from 1941, for which you can also download the score here for free. In this piece, and in his operas of the 1930s, he actually employed Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone method, but it’s not audible because he used it in the context of tonal writing. So he was interested in newer musical developments, but used them in his own way.

Paul was quite successful. In 1913 he was appointed principal conductor at the opera house in Freiburg. He founded and conducted the Danish Philharmonic Society from 1920 to 1926, and during that period he conducted music of Schoenberg. (However, contrary to some sources, he never studied with Schoenberg.) He even invited Schoenberg to come and conduct his own music in 1923. Here is a photo from 1923 in Copenhagen, showing von Klenau (the tall man), Schoenberg, and soprano singer Marya Freund, who premiered a great deal of modern music including Schoenberg’s:

Paul was friendly with the composer Alban Berg as well. Later, he was a conductor in Vienna and Stuttgart. Suffering from hearing loss in his final years, Paul returned to Copenhagen in 1940, and died there in 1946.

Paul was married in 1903 to Anne Marie (sometimes written Annemarie) Edeline Simon (1878-1977—a long life!), a member of an incredibly accomplished Jewish family (more on that below). Here are Paul and Anne Marie together in an undated photo—Dan Morgenstern’s grandparents on his mother’s side:

You will notice on the family tree that Anne Marie lived in Bavaria from 1912 onward, and that at some point, she and Paul were divorced. So let’s explore further:

Dan continued the story of Paul von Klenau in his JOHP interview: “He married my grandmother [Anne Marie Simon], who was the granddaughter of a famous man who played a role in nineteenth-century German history insofar as he became one of the first Jewish delegates to the German Reichstag and was an opponent of [Chancellor Otto von] Bismarck’s.” This man, Anne Marie’s mother’s father, was Leopold Sonnemann (1831-1909). He was a founding member of the liberal German People’s Party and its first representative to the Reichstag house of the German parliament under Bismarck. In addition to these accomplishments, he was the founder and first editor in 1856 of the important liberal newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung. In 1933 the Nazis began to cut down on the paper’s Jewish employees, but the paper survived with a Christian staff until the Nazis finally shut it down in 1943. (Today’s Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, founded in 1949, is an independent publication, not a continuation of the Frankfurter Zeitung.) Anne Marie’s brother Heinrich was the editor for many years, with her brother Kurt and their mother as part owners, until 1934, when a combination of political and financial troubles forced them out, as reported in New York City’s Jewish Daily Bulletin, June 3, 1934:

But back in 1912, when her family was still thriving financially, Anne Marie bought a country estate in Beuerberg, Germany, in Bavaria. Paul and Anne Marie both lived there, when he wasn’t traveling to conduct. Their summers were spent at his residence in Frederiksberg, near Copenhagen.

In 1924, Soma Morgenstern and Paul were visiting their mutual friend Alban Berg in Vienna, and that’s where Soma met their daughter Inge. Anne Marie and her family were not religious Jews, so it is not surprising that Inge was raised in Paul’s Lutheran faith. In fact, the right side of the family tree above states that Anne Marie’s mother converted to Christianity and was baptised at the age of 50. Several others of Anne Marie’s ancestors were raised Christian or converted. Still, it is probably no accident that Inge waited until her parents were divorced to marry her Jewish boyfriend Soma. For unknown reasons, Anne Marie and Paul von Klenau were divorced on April 14, 1927. In 1928, Inge left the Lutheran Church so that she and Soma could marry in a civil ceremony. Their one child, our Dan, was born on October 24, 1929. In providing for the family, Soma benefited greatly from his wife’s family’s connections. Around the time that they married, he was hired as the cultural correspondent for their newspaper, the Frankfurter Zeitung, until the Nazis forced him out in 1933.

But what happened to Paul after he left the Morgenstern family? He eventually separated himself not only from his Jewish family, but from all Jewish friends, and he became a member of the National Socialist, aka Nazi, party. In late 1935 he received a letter from the Nazi music critic Friedrich W. Herzog asking about Paul’s “non-Aryan relatives.” His handwritten reply is dated November 14. The following deeply revealing letter has never been published in English before. I found it in a German reference book about composers under the Third Reich, and I translated it using Google and my own knowledge. Paul wrote:

I assumed that you knew that I was married to a Jewish woman. But I have been divorced for 9 (nine) years and have no contact [literally “no traffic’] with her or her family. You will spare me from having to speak of this bitter experience of my life. You know my attitude towards the racial question. I repeat that I am personally of pure Aryan (Germanic-Nordic) descent on both my father's and mother's side, and that my ancestors were German knights and served at the Danish court as chamberlains and high-ranking officers from the end of the 19th century. I am personally well acquainted with my king [of Denmark]. I can only answer other questions once I have received an answer as soon as possible to the question of whether the fact of my divorce, as communicated to you, plays a role in your or the N. S. [National Socialist] cultural community's attitude to my work. I can expect complete openness.

“I can expect complete openness ” means "something like “I trust you to be completely open with me.” Some say that Paul was an opportunist rather than a devoted Nazi—for example he did not sign his letters with “Heil Hitler,” not even when responding to one that ended that way. This letter certainly sounds like someone fighting for his career, but I think you’ll agree with me that he also goes a bit too far and sounds like someone who really believes in what he is saying. For instance, was his first marriage experience really “bitter”? (He uses the same word in German, spelled “bittere.”) And he wrote “9 (nine) years,” writing the number both ways, to emphasize how long it had been. (They’d been legally divorced for eight-and-a-half years, but with separation before, nine was probably about right.)

As one would expect from this letter, his second wife had solid “Aryan” credentials, born in Vienna in 1892 as Margaretha Anna Johanna Hentschel. She took the name von Klenau until Paul passed away, and then married someone named Klimt, but I have not found any relation between her and the famous painter Gustav Klimt. She came to the U.S.A. in 1959 (one record suggests 1961), and died a few years later.

Paul was also challenged at times about why he was using the “Jewish method” of twelve-tone series or “serial” composition. According to Schoenberg, in an essay written in 1947 (and re-published in the book Style and Idea), Paul responded by publishing an essay “in which he ‘demonstrated’ that this method is a true image of national-socialist principles”! Schoenberg was clearly disgusted by this deceitful approach, but it worked, and Paul was probably the only Nazi composer who was allowed to use the twelve-tone system. And the honors kept coming in: In 1941 he was chosen for the planned Internationalen Kulturkammer, the Chamber of Culture with which Hitler planned to control all of the arts if he won the war. And in 1944, Paul was on the list of composers approved for radio broadcast by the Reich. Even Berg was not on the list because, although he was a Christian and of “Aryan” ancestry, he refused to give up his close friendships with Schoenberg and other Jewish musicians. (Schoenberg had converted to Lutheran in 1898, but as I’m sure you know, Hitler’s regime taught that Jews were a “race” and that Jewishness could not be changed.)

From Dan Morgenstern’s birth in 1929 onward, the story has been told. In fact, you can see Dan himself talking about his mother and father and their families, and how they fared under the Nazis. Just watch this interview of Dan with Monk Rowe for the extensive Filius Archive at Hamilton College—start at 7:15 and continue to 30:50. I’ll summarize briefly and add a little bit of new information:

When his mother went into labor with Dan she went to Munich, where her own mother Anne Marie had been born and probably still had family. It was also the closest big city to their estate in Bavaria. So Dan was born in Munich, but his parents lived in Vienna, and he considered himself Viennese. It is usually reported that his father, Soma Morgenstern, left Vienna on March 12, 1938, the very day that the Nazis came to power in Austria (the Anschluss). But Soma himself, in a letter addressed to Berg’s widow in 1970 but apparently never mailed, wrote that it was the day before: “It was my good luck to have fled from Vienna just one day before Hitler marched in. An ‘Aryan’ friend…knew, from a reliable source, that the last train to Paris, on which one could leave without a permit, would be leaving; the next day [when Hitler arrived] a permit would be needed.” (This letter, which contains quite a bit more new information, has been published in German. This English translation is by my friend, Berg authority Mark DeVoto, and is available at the extensive website for Soma.)

But Dan was ill in bed with a serious case of scarlet fever, so he and his mother had to stay behind. Soma spent time in France and, after numerous adventures, he ended up in New York City in 1941, with the help of the heroic rescuer Varian Fry. Meanwhile, Soma’s attempts to send for Inge and Dan were not successful, but they were able to go to Denmark in August 1938 because of her von Klenau ancestry. In October 1943, they were among the many Jews who were famously saved by Danish citizens and sent to safety in Sweden. After the war they went back to Denmark, and finally arrived in N.Y.C. on April 21, 1947, reconnecting with Soma.

I’ll conclude today’s essay with something I put together for you—Dan Morgenstern surrounded by his parents:

Left to right: Soma Morgenstern Dan Morgenstern Inge v.Klenau Morgenstern

NEXT TIME: The amazing connection between the ancestors of Dan Morgenstern and today’s guitarist-composer Peter Hand.

All the best,

Lewis

Excellent! Great work, Lewis!

Amazing. A fantastic story. I knew Morgenstern had 'something' to do with Denmark. But like many who met him and used the jazz studies facilities at Rutgers I didn't enquire about that part of his history. Both he and his colleague were very helpful.