(Paying Subscribers, at the bottom you will find a scan of Inez Cavanaugh’s notes to Ellington’s 78 rpm set, and some of the story behind it.)

Among many other accomplishments, Leonard Feather compiled the first jazz encyclopedia in English—a collection of short musician biographies from A to Z. (Feather’s bibliography shows that he was aware of the earlier one in Italian, published in 1953.) And his was one of the only such books ever that was assembled by personally contacting the musicians, whenever possible, and having each one fill out a questionnaire. You may know the 1960 New Edition of the Encyclopedia of Jazz, or the last edition, expanded and completed in 1999 by his fellow journalist Ira Gitler. But you might not know the first edition, for which he asked Duke Ellington to write a foreword.

Ellington agreed to do it, and he and Feather decided that it would be easiest if Leonard interviewed Duke on tape, and then wrote up the foreword from that conversation. Many years later, Feather gave the tape to an assistant, Steve LaVere (a blues and jazz researcher). LaVere gave it to jazz historian Steven Lasker, who donated it to the Library of Congress in 2008. Lasker has kindly allowed us all to listen to it today, and in the next essay.

The tape box said 1955 but it’s not known who wrote that. Regardless, that is the year that the book was published, and probably, but not necessarily, when the conversation was recorded. It was originally announced in Billboard magazine that the book was to be published on September 5, 1955, but as Downbeat (April 4, 1956) noted, it actually came out in November:

The book was reviewed, glowingly, in Downbeat on November 30, 1955, so it must have come out early in the month. For Duke’s interview to be transcribed, sent to the publisher, and typeset, in time for publication in early November, it would have had to have been conducted early in 1955, or else late in 1954. The Foreword closely follows what Ellington says, with Feather’s comments deleted, so it is helpful to have it handy while listening to the tape. Here it is from the 1955 first edition (it appeared, unchanged, in the 1960 “new edition” as well):

Some of the audio is missing or noisy during the first minute because of deterioration of the tape. But after that, it’s easy to hear the discussion. Leonard’s wife Jane is also present. She offers Duke some food, but he says no thank you, he’s “stuffed.”

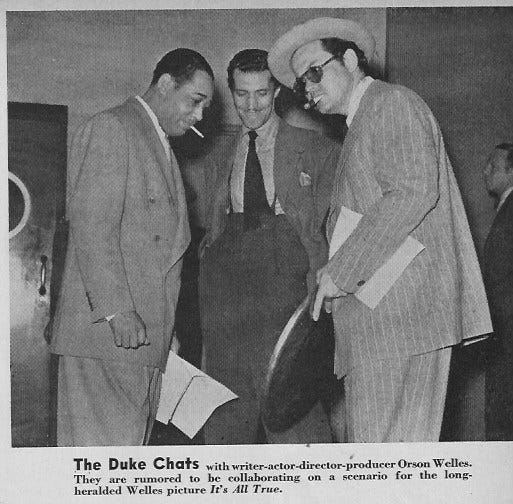

To begin, Duke tells the story of meeting Orson Welles in Los Angeles in 1941. He had seen Duke’s musical revue Jump for Joy the night before. Welles asked if Duke would prepare a history of jazz, with original music, for a documentary film that was to be called It’s All True. (As you may know, the film was intended to have other segments as well, but Welles never completed it, and did not film any of the proposed jazz segment. Some footage of the other sections survived and was presented in a documentary in 1993. The untold story of the jazz segment is kind of amazing and I am working on an essay about that.) Duke is very specific about Welles’ big budget. He says that he was paid generously in installments, but the project was aborted before he had to hand in any music. He also notes that Welles also hired several “technical directors”—that is, historical consultants. “I don’t know how you missed that one,” he tells Leonard. “That was juicy”—meaning, you missed out on a lot of money. At 3:15 Duke mentions Dave Dexter, later of Capitol Records, as one of the consultants, but he is not known to have been involved. Probably Duke spoke in error and meant to say Dave Stuart, who was indeed a technical director for the project.

The planned film was reported in Downbeat magazine, December 15, 1941, with a cropped version of the photo below. Steven Lasker informs us that it was taken at a CBS owned and operated radio station, KNX, 6121 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood. This uncropped photo is from Music and Rhythm, May 1942. The man in the middle, not identified here, is Duke’s singer Herb Jeffries:

Feather then gets Ellington talking about how he would have told the history of jazz, and at 3:56 Duke offers a long, somewhat fanciful story about Congo Square and Buddy Bolden. Then he returns to the Welles story at 6:12—he says that he wrote 28 bars of trumpet music that Welles never asked to see. Leonard and Jane are both astounded when Duke confirms that he was indeed paid a total of $12,500, in advance. Jane asks if he might still be able to collaborate on this with Welles, but Duke replies that Welles no longer had that kind of money.

Duke mentioned that he prepared by reading all the jazz history books that were then available, and at 7:20 he tells Feather that he was not impressed. At 8:00 Duke asks, “Did you ever read my history of jazz?.” Duke must mean his 7-part series "Jazz as I Have Seen It," which ran in Swing magazine during 1940. But Feather doesn’t seem to know about that. so he asks “You mean the thing you did with Inez?” Duke replies, “No, that’s Black, Brown and Beige.” What they are referring to are the notes written by Inez Cavanaugh (a Black journalist and singer who was the partner of the Danish jazz fan and producer Timme Rosenkrantz) for the 78 rpm release of pieces from the suite. (Paying Subscribers, below you will find a scan from my own 78 rpm set, and some of the story behind Inez’s notes.)

Duke says that his version of jazz history would use a Greek choir, and he traces the progress of jazz from Africa to the Caribbean and New Orleans and so forth. When Leonard asks him at 10:00 to name some key figures, he says you’d need to ask the Lion (Willie “the Lion” Smith), but he does mention D.C. pianists Sticky Mack and Louie Brown. (Brown was still alive then.) He says at 12:23 that the most famous piece in the early 1900s was “The Dream,” a “tango type thing,” which gets them talking about the so-called Latin influence on jazz.

At 14:40, both Duke and Feather speak poorly of Jelly Roll Morton. Duke says he played like a high school teacher, at best. At 16:55, Jane excuses herself to go to sleep. The conversation continues, and Duke is astounded that Feather hasn’t heard pianist Lucky Roberts. We end this installment there, but there’s more to come.

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Paying Subscribers, below you will find a scan of my own 78 rpm Ellington set, and some of the story behind the notes.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.