Duke Ellington, The Man with Four Sides,2: More Music Recordings, With a New Source

Last time we introduced this musical and listened to some recordings of the songs. We ended with a brief excerpt of a 1952 rehearsal of “She.” “She” and four of the other songs, with sheet music, were copyrighted on September 19, 1955 with words and music (w & m) by Ellington, as you can see here from my copyright records search:

But the evidence shows that the melody of “She” was not by Duke. A year before the rehearsal, it had been commercially recorded on April 17, 1951 by a small group of Ellingtonians as an instrumental, with Strayhorn at the piano. (Duke wrote the words later.) It was released on 78 rpm on the label named for Duke’s son Mercer, and the band was called “The Coronets.” (Mercer and Leonard Feather ran the label, with financing help from Duke.) And here is the most significant detail: Although the copyright record shown above lists Duke as the composer, the original label says that this was written by Juan Tizol and Louis Bellson:

That makes sense, because it is very definitely in the vein of Tizol’s other pieces, such as “Caravan.” And drummer Bellson was an excellent composer as well. The other side of the 78 was a known Tizol composition, “Moonlight Fiesta,” aka “Puerto RIcan Chaos.” Also recorded that day were pieces by Cat Anderson and Paul Gonsalves, so it appears that the goal of the session was to record pieces by the band members under Strayhorn’s direction, specifically not pieces by Duke. Besides, Duke was under contract to Columbia Records at that time. And, finally, it is impossible to believe that Duke’s own son would not have given him credit if he had written this piece!

But when it was time to copyright the piece three years later, Duke gave himself credit for writing the words, and took the “leader’s prerogative” by listing himself as the music composer as well. Hundreds of bandleaders and singers used to list themselves, inaccurately, as authors or coauthors, as we have noted on occasion and will note again. Besides, for fundraising purposes Duke wanted to say that the show was entirely written by himself, as we’ll hear shortly. And Tizol and Bellson had both left the band, so he didn’t have to consult them in person. Finally, let’s listen to the tune in that 1951 recording:

Shortly, you’ll hear the vocal version of “She,” complete. But Ellington never wrote the music for many of the song lyrics that were in his script. Of course, he would have finished them if the show had moved forward.) There was also a planned “Fugue Finale” but Duke’s notes indicate that it would have combined elements of the other songs, so it would not have contained new music.

SO—after working on it for years, Duke completed the show by early August 1955. And the next step was to try and get it staged. It has been known for quite a while that somehow Duke and Dave Garroway, a popular radio and TV host, had talked about Duke’s need for investors. Garroway was the initial host of NBC Radio's Monitor program that, starting June 12, 1955, aired every weekend from the Radio City building (named for its radio studios) in Rockefeller Center, Manhattan. (Yes, the famous “30 Rock.”) So he actually invited Ellington to come on Sunday, August 28, 1955 and “pitch” his musical. (This was once listed as a December event, but the late Ellington researcher Jerry Valburn was actually in the studio that day and provided the correct date.) Someone recorded this broadcast on tape from a radio speaker, and a very few collectors have heard that over the years.

But apparently Garroway also arranged for the broadcast to be professionally recorded and transferred to a one-of-a-kind LP, so that Duke would end up with a short “demo” (demonstration) disk—less than 10 minutes per side— that he could play for potential investors. This disk has much better sound than the tape, and jazz historian Steven Lasker has kindly shared the original disk with us today. The disk contains only the songs, not all of the talking.

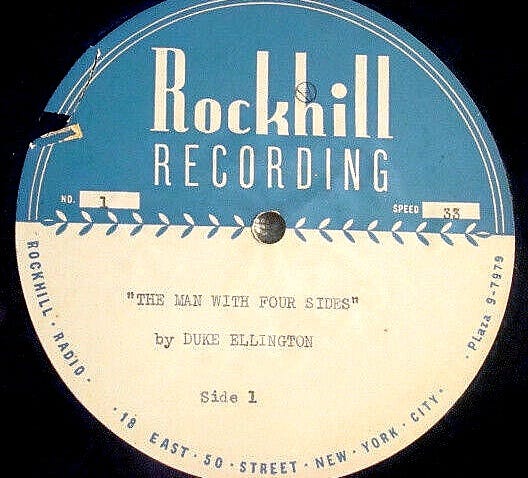

The recording was made by Rockhill, at 18 East 50th Street. This was only about a block away from Radio City, and was probably used regularly by NBC radio when they needed something recorded. Here is the label of Duke’s private demo LP:

We also thanks Ellington researcher Anders Asplund, who has shared with us the complete broadcast as recorded off the radio. So we will hear the talking from Anders’ tape, and the songs from Duke’s own disc, courtesy of Steven Lasker.

Garroway announces that Duke is looking for “angels,” that is, investors to help produce this show. (Since the late 1800s, people who invest money in a forthcoming project, similar to GoFundMe today, but especially in a theatrical production, have been called “angels.”) Let’s listen (courtesy of Asplund):

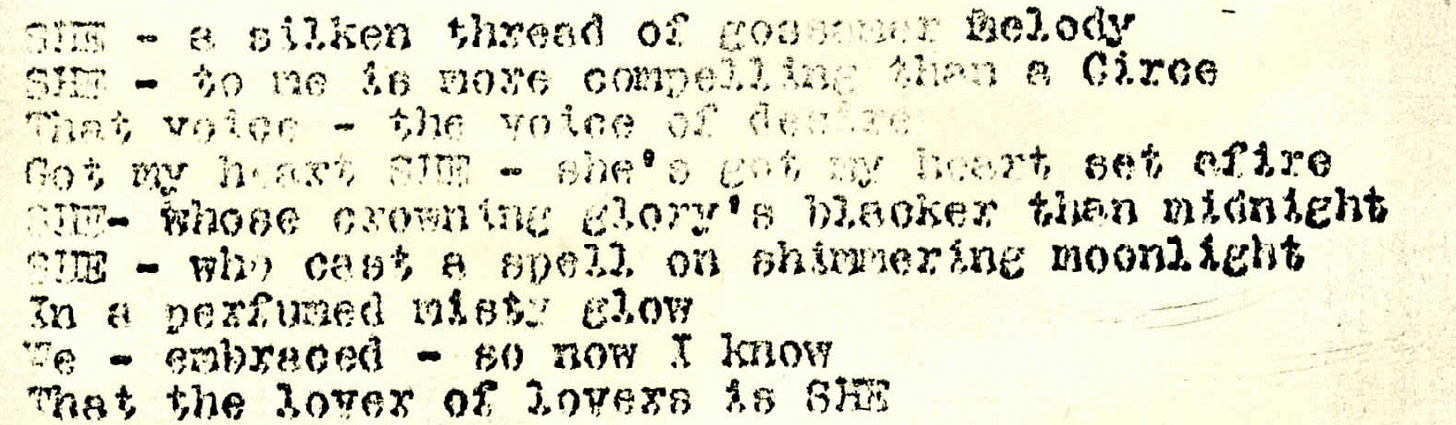

The end of Garroway’s introduction is repeated on side one of Duke’s LP, but with notably better sound (courtesy of Lasker). Then, Ellington talks through the story of the show, while Jimmy Grissom and Marion Cox sing, accompanied by Luther Henderson (p) and Jimmy Woode (b). First you’ll hear “Like A Train.” (As we explained last time, it’s the melody that was popularized as “Night Train.”) Marion Cox sings without words (in classical music that would be called a vocalise, as opposed to jazz “vocalese.”). Then, Grissom sings Duke’s words for Tizol’s melody, “She.” Here are the lyrics as Duke typed them into his own script:

After that is “It’s Rumor.” Listen, please:

On side two of the LP, Duke speaks for a while to set up Cox’s performance of “Twilightime” (sic). (Duke definitely wanted it to be one word, and on the copyright he used one “t,” as I just did, but in his script he typed two “t’s.”) She also performs a bit more vocalise as Duke ends this very abbreviated tour of his show:

Now Garroway talks with Duke, and tells listeners to contact him if they want to be “angels.” Notice that Duke specifies that the show is “completely” by himself—as I noted above, that’s one reason he didn’t credit Tizol for “She”:

Garroway even arranged for Ellington to record two more songs after the broadcast, that same day. For these, an original disk has not been found, but a tape exists and has been shared with us by Asplund. For these, since Duke didn’t have to narrate, he took over the piano from Henderson. Luther Henderson (1919-2003) was well known as a Broadway orchestrator and he also was associated with several projects of Ellington and Strayhorn, together and separately. (By the way, around 2000 a mutual friend offered to introduce me to Henderson. I foolishly waited too long, and he passed away.)

We’ll hear Ellington accompany Grissom singing “Weatherman,” and Cox singing “The Blues,” originally from Black, Brown and Beige but intended for the new show as well. This copy is missing the very ending:

Well, the broadcast was a success: An angel did come forward, and Downbeat announced that Lorella (sic; not Loretta) Val-Mery would produce:

Val-Mery (1909-1983) was a noted publicist (a.k.a. press representative) for many Broadway shows from 1941 into the 1960s. Her full name was Amelia Ellen Lorella Grimes Val-Mery and she was born on February 17, 1909, in Liverpool, England. Her family moved to N.Y.C. in 1913, and she married Nino Brugnola in 1927 and lived in Manhattan. But for unknown reasons, her agreement to produce the show fell apart, and by the fall of 1956, “Man with Four Sides” was said to be in the hands of famous actor and director José Ferrer, and was planned to open in Boston during the 1956–57 season. That too never took place. The only production I know of was a staged reading in February 1997 at St.Peter’s Church in Manhattan (the “jazz church”) for which theater scholar and musician John Franceschina reconstructed several of the numbers from Ellington’s sketches. (Page 92 of Franceschina’s book provides details of Ellington’s proposed budget of around $400,000, and also quotes a letter from another potential director.)

We are far from finished studying this show. Next time I will share with you some pages from Duke’s actual typed script!

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Thank you to Steven Lasker, Anders Asplund, Bo Hauffman, Olivia Wong, and Len Pogost for assistance with this essay.