(Paying subscribers, Substack only allows one “embedded” video per post, so I’m sending you separately the rare Coleman Hawkins silent outtake from this film.)

If you haven’t seen the first four posts about Parker’s films, please browse through previous posts—I posted part 1 on December 3. This 5th episode will be the last post about the 1950 JATP film project by Norman Granz. At the top of this post you will find ten minutes of outtakes, first those with sound (remember, the sound was recorded separately, but it still makes it more enjoyable), and then the silent outtakes. The pianist whose hands are shown at the beginning is Hank Jones, age 32. Ray Brown is on bass, and Buddy Rich on drums.

I mentioned that documentarians get access to the vaults. The BBC found a priceless clip of Bird breaking up with laughter at Hawk’s attempt to match the recording, s you’ll hear the narrator explain. (Hawkins must have been playing out loud, not just moving his fingers.) Bird’s humor attack gets to Hawk, and he appears to be holding back laughter as well. Then, evidently, someone off to the right, probably Granz or Mili, asks Parker to cut it out. That’s the first item that you will see above.

By the way, I wonder if people understand that the person who posts can delete inappropriate comments on Youtube. There are all kinds of absolutely wrong comments online about how Bird “obviously” thought Hawkins was a jerk, etc. These should be deleted. Parker, and his entire generation, idolized Hawkins, because he was a brilliant musician who carried himself with dignity. Besides, Hawkins was one of the few of his era who hired beboppers—Monk, Dizzy, Miles, Fats Navarro, J.J. Johnson, Max Roach, and others—and was comfortable playing with them. Bird laughing at Hawkins? Never. Laughing with him? Sure.

You’ll notice at the beginning of this footage that Parker moves his chair closer to Hawkins. Granz suggests in his spoken introduction on the DVD that Bird spontaneously decided to do that, which is clearly false since Mili was famous for carefully staging everything. That was part of Granz’s plan to make this appear to be a spontaneous jam session, which of course it was not.

The second item is the two complete film clips with Parker, but with alternate footage. A special feature of the DVD is that there is an option to watch outtakes synchronized to the music. That is what you’ll see here, a version of the two pieces that uses different footage (including Bird laughing). Sometimes both versions have the same images, and often they are different. (The “official” version is at the link below.)

Finally, you’ll see about 4 minutes of silent outtakes of Bird. You’ll recognize some that had appeared in the parker and Joe Albany documentaries. There’s also about a half-minute of Buddy Rich at 8:26, just because it was too complicated for me to edit it out. It’s fun, anyway. And then Bird returns. NOTE: This silent footage didn’t play well on this page, so I have posted a better version here.

After seeing all that above, I’m sure that you are eager to watch the two performances by Parker from this film, in the form that they were finally edited and released in 1996. Notice that on this version there is no laughter near the beginning of “Ballade.” Instead, Parker nods toward Hawkins as if to say, “That’s the master!” (Please ignore Youtubers who think Bird was making fun of Hawkins here as well!)

The performance of "Ballade" is magnificent. The structure of the performance is AABA,BA (every section is 8 measures). Hawkins plays the AA, then Bird plays the BA, then Hawkins plays BA. This may seem odd, but in fact this “one-and-a-half chorus” arrangement was absolutely standard in those days. The idea was to break up the potential monotony of too many A sections in a row (as in AABAAABA), and also to shorten the performance to be sure it would fit on a standard 10-inch diameter 78 recording (which typically was limited to a maximum of about three-and-a-half minutes).

At 1:20, Parker plays an astounding fast phrase that is perfectly, delicately articulated. His solo has tremendous variety, and ends with a swaggering, soulful and memorable phrase at 1:49. Though it’s rarely noted, Bird’s playing didn’t stand still, but rather evolved over the years, and he developed this kind of richly layered ballad playing by the end of the 1940s. Another amazing example is his solo on “Embraceable You” at JATP in 1949—here it is spliced in right after Lester Young’s solo (on the full recording there is a trombone solo in between).

“Ballade” is followed by an up-tempo performance based on “I Got Rhythm” chords (musicians call this “Rhythm changes”). Bird jumps right in with no written theme. Buddy Rich solos for a full chorus, and then Bird plays a final chorus. The only prepared theme is what he plays during the last 8-bar A section. Here are the two performances, with an outtake between the two pieces, which is the way it was released:

(The footage for the 1950 film also includes titles with Lester Young and others, but no more titles with Parker. We will ge to the Pres films when I do another series called Every Film Clip of Lester Young, which will include some very rare items.)

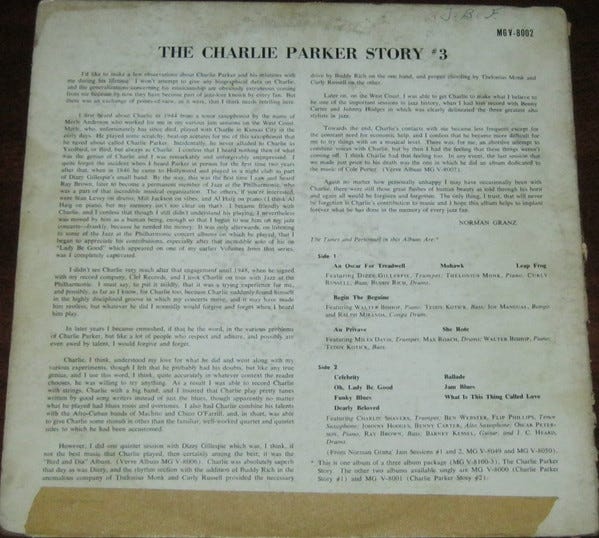

Although the film was not released until much later, the soundtracks for the two Parker numbers in the film were issued in 1957, two years after Parker died, on an LP, The Charlie Parker Story #3, Verve Records MGV-8002. One number was called "Ballade" and the other "Celebrity":

But on the label of the LP, the fast title was spelled "Celerity":

When I purchased the LP in the mid-1960s I assumed that was a typo. However, as researcher (and my one-time student) Michael Fitzgerald has noted, "Celerity" is a word, and in fact it’s an appropriate word: "Celerity" means "Rapidity of motion; speed; swiftness." The title makes sense as a contrast with "Ballade." (Jazz musicians use “ballad” to mean anything slow—nothing to do with folk ballads.)

Although artists did not always name their recordings (I’ll discuss that another time), an accumulation of evidence indicates that Parker did in fact intend to call the second number "Celerity," but that Granz and anyone else involved in its release had never heard of the word and assumed that Bird had meant to call it "Celebrity." The Verve log book says "Celebrity," as the late researcher Phil Schaap confirmed to me. A search at the U.S. copyright website shows that it was initially copyrighted as "Celebrity" (apparently by Bird’s legal widow Doris Parker in 1958, to correct for the fact that it had not been copyrighted earlier)—but with the "additional title" of "Celerity." No doubt this method was adopted because the song had been released with both titles. If Granz rather than Parker had titled this number, where would “Celerity” have come from?

The story continues: In 1986 Parker's son, the late Leon Parker (1938-2004), registered it again for copyright (at that time copyrights had to be renewed after 28 years). This time the name "Celebrity" was removed and only "Celerity" was given. In the listing at BMI.com, the original registration said "Celebrity (Legal Title)" but then it was registered again with a new number (no date given) and this time it said "Celebrity or Celerity (Legal Title)." As with the copyright records, this seems to have been done to correct the earlier mistake of naming it "Celebrity."

Since the piece was copyrighted in Parker's name, I could easily believe that he said "Celerity" and that Granz, or the recording engineer, or whoever wrote it in the log book figured there was no such word and assumed that he must have meant "Celebrity." JATAP Music (Jazz at the Philharmonic) was listed as the publisher, which means that Granz or someone associated with him filed the copyright, not Parker personally, and thus there was room for them to commit that error. Furthermore, the title “Celerity” is used in books such as The Charlie Parker Omnibook and David Baker's How To Play Bebop, vol. 3. This is in fact the title given by the publisher, Atlantic Music Corporation, and when the authors requested permission to print the music in their books, they must have been told by the publisher that the correct title is "Celerity."

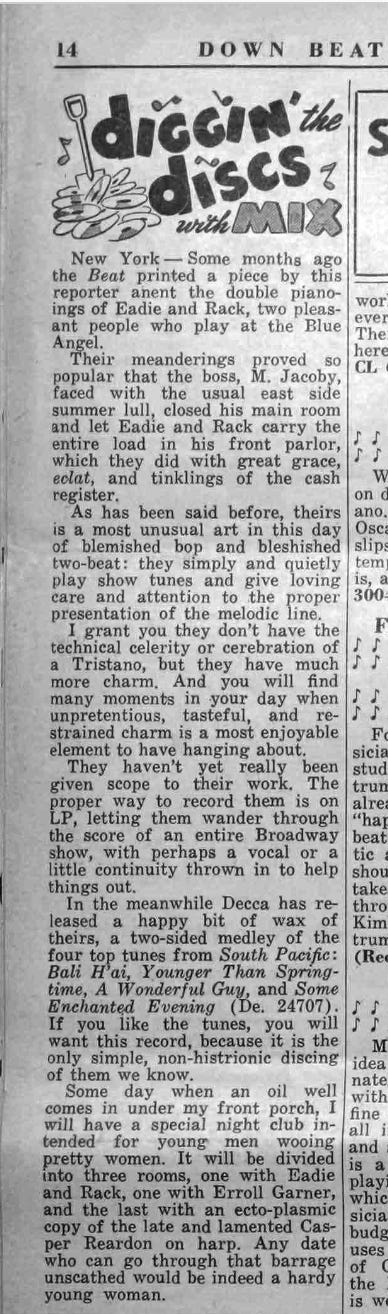

Finally, Parker, like Gillespie, Barry Harris and some others, was fond of learning new and unusual words. The word "celerity" appeared in Down Beat's regular record review column, "Diggin' Discs with Mix," unsigned but usually authored by Mike Levin, in the issue of October 7, 1949, page 14:

Talking about some local pianists whose music he enjoys, Levin notes that "I grant you they don't have the technical celerity or cerebration of a Tristano." So the word was getting into jazz circles just a year before the September 1950 sessions. In short, for all the above reasons, "Celerity" it is!

"Ballade" does not present any title and copyright problems. It was copyrighted under the names of the two soloists: "Parker-Hawkins." (Probably the reason that Parker’s name is first is that he was under contract to Granz.) However there has been some confusion about the source of its chord changes. "Celerity" is clearly based on standard "I Got Rhythm" changes, so that’s easy. Meanwhile, "Ballade" has been listed as having the same changes as "I Got It Bad (And That Ain't Good)," but that bridge doesn't fit at all. The fact that the A section fits pretty well is not significant, because the A section uses a fairly standard type of sequence that would fit a number of songs. U.K. jazz scholar Brian Priestley has pointed out that "Ballade" is definitely "As Long As I Live," and that this was a favorite sequence for Hawkins around this time. In fact Hawkins had used this chord sequence on a Granz recording session just a year earlier, August 29, 1949, where it was called "Platinum Love." (Thanks to Priestley for this information, which is also in his book, Chasin' the Bird.) Hawkins also used the same sequence later on one of the tracks from the "Les Tricheurs" film soundtrack. (This Marcel Carné film was released in 1958; a Hawkins recording is heard in the slow dance party sequence at around 16 minutes.)

By the way, there are several songs with this title. The one that fits "Ballade" is the most famous, the one written by Harold Arlen and lyricist Ted Koehler for the 1933 show Cotton Club Parade. The first line is "Maybe I can't live to love you as long as I want to." (There is another song of the same name whose first line is "As long as I live"—Woody Herman used to perform that one in 1944.)

Older Parker discographies such as the one by Piet Koster and Dick M. Bakker (Holland: Micrography, 1974-6, Vol. 2, 1975, p.26) listed a third title, "Body and Soul" featuring "probably" Parker, Hawkins, Flip Phillips, Harry Edison, Hank Jones, Brown, and Rich with a vocal by Ella Fitzgerald. The title was thought to have been recorded a month earlier than the other two. (Koster and Bakker reported that some of their sources even thought that the films and all the recordings including this one came from as early as 1945-6, which is clearly wrong, based on the Down Beat notices which you saw lst time.) Such a title never existed, and it’s unclear where this idea came from. Possibly someone had mistakenly reported that "Ballade" was based on "Body and Soul," and this got eventually translated into a separate listing. Or, it may be that this was an erroneous report of a version that is now available, but was not released at that time; Hawkins played "Body and Soul" at the JATP Carnegie Hall concert on September 18, 1949, and later in the same concert, Ella Fitzgerald sang with the all-star personnel including Parker (but not Hawkins, and with Roy Eldridge rather than Edison, and Tommy Turk added on trombone). In any case the correct information is at Peter Losin’s website, the best source for both Parker and Miles Davis.

Saxophonist and historian Loren Schoenberg has pointed out that all of the VHS versions of the film are running too quickly. The recording of "Ballade" is in F and "Celerity" in B flat, and the fingerings on the film match those keys. But the film of "Ballade" is in F sharp, and "Celerity" is in B natural. (The Lester Young titles also run too fast.) Apparently, the film was playing too quickly when it was originally transferred, and all versions have been based on one initial transfer. For the DVD version, they went back to the original tapes, and I recall that the DVD plays at the correct pitches. But at the Youtube link above they still play sharp. And unfortunately after I uploaded the outtakes to the top of this page, they play a half-step slow (E and A)! I haven’t found a way to fix that yet. (The 1.25 speed option is too fast.)

Something tell me that at this point you are saying, “Can you please get on with more celerity?!! You are taking forever on this 1950 film by Norman Granz!”

Okay, okay—I’m ready to move on. The next surviving footage of Bird is another short, silent clip. Coming soon!

All the best,

Lewis

(Paying Subscribers—you’ll get bonus Hawkins clips shortly in a separate post. THANKS!)

Share this post