Last time I gave you a very detailed introduction to Coltrane’s uses of texts, including “hidden” texts, in his music during 1964 and ‘65. But what about “Alabama” from 1963? What do we know about its genesis, and why is there a pervasive opinion that it has a hidden text? Well, John’s pianist McCoy Tyner once told journalist Ashley Kahn that the rhythms of the piece were based on the rhythms of a speech by Dr. King that John saw printed in a newspaper. (See page 79 of Ashley’s 2002 book on A Love Supreme.) Since then, people have been searching without success for a text that will fit the melody in that way. I too would like to believe that Tyner was right about this. And the style of the piece absolutely does sound like a recitation. Listen to the beginning, and think about the examples we heard last time:

The critic Francis Davis spoke with Tyner and Jones and learned that Coltrane did not tell them the inspiration for the piece, or even its name, when they recorded it in the studio on November 18, 1963. But I don’t think John’s silence about that is significant. For one thing, Coltrane frequently recorded pieces before he had names for them. (As I’ve shown, it took him almost three years to name “Impressions.”) Besides, as I’ve also noted, he hated to be didactic or condescending. In fact, as I mentioned last time, he never said anywhere in print that the piece was a response to the sick and brutal Birmingham bombing of September 15. But I think we are right to assume it — why else would a piece be named “Alabama” so close to that heinous and criminal event?

In fact, I wonder if Coltrane was more shaken up by the news of the bombing than we know. On Monday, Sept. 16, 1963, the day after the bombing, he mailed a Mutual of Omaha Travel Accident Insurance Policy—which would pay up to $100,000 if there was an accident—to his mother in Philadelphia, before taking off on a flight from Buffalo, New York, to his next gig in Cleveland, Ohio. (This policy came to light in an auction of Coltrane’s documents in 2005.) Was he concerned that there might be more violence to come? Or did he always buy travel insurance — it was, and still is, an option on every flight — and it’s just a coincidence that the only one we have a record of is this one? Please understand, this might mean nothing, but I think it’s worth considering because of the timing.

When the quartet performed the new song just a few weeks after its studio recording, for Ralph Gleason’s public television show Jazz Casual, Gleason announced it as “Alabama.” This was first broadcast in 1964, but Gleason’s late widow Jean told me years ago that it was recorded on Dec. 7, 1963. Let’s watch Gleason’s announcement and the very beginning of the music, where Coltrane plays exactly the same phrase that we just heard from the studio recording. (Notice that you can see Alice Coltrane sitting in a chair on the left side of the screen.)

So Tyner knew before December 7 that this was a response to the bombing in Birmingham on September 15. And it’s easy to imagine him talking with John about it, and learning that it was based on a newspaper report of Dr. King’s moving eulogy for the four murdered girls.

Some have said to me: Maybe Tyner was wrong, and Coltrane’s inspiration was a radio broadcast of the eulogy. Well, first of all, memories do need to be verified, but there’s no reason to discount what Tyner said right away, without checking. Second, I did indeed check, and my research indicates that the speech was definitely not broadcast “live,” but was recorded locally, on location. Third, it appears that if and when it was broadcast, it was many years later, most likely not even during Dr. King’s all-too-short lifetime, but excerpted in the many radio and film documentaries that came later.

And for whatever reason, the recording is now missing the first paragraph, as well as two paragraphs in the middle where Dr. King addressed the bereaved families. (We know what he said because we have his written text.) Dr. Clayborne Carson, in his collection of King’s speeches titled A Call to Conscience, notes that those portions had been cut out of the original tape for one of the later radio broadcasts, and apparently discarded. (Yes, in the old days people often threw out the pieces of tape that they cut out during editing; even engineers editing jazz albums were known to do that.)

In short, I think we need to forget about the theory that Coltrane “learned” the speech from the radio. It wasn’t broadcast. But here’s the answer: I found that excerpts of the speech were quoted in many newspapers around the USA on September 19, 1963, the day after the funeral. Of course, The New York Times and other major papers had their own reports, and typically they quoted two or three sentences of Dr. King’s eulogy. But a reporter named Hoyt Harwell wrote a more detailed report for the Associated Press (AP), the independent news cooperative that covers events for the many small newspapers—at that time about 1,800 of them—that couldn’t afford to employ a full staff of reporters. Harwell, a white native of Alabama, later became the AP’s Birmingham Chief from 1966 until he retired in 1992. And his article has the most substantial quotes from Dr. King’s eulogy to be found in the press of that time.

The reporters wrote down what they heard: in those days, before recording was standard, reporters were required to take quick notes, sometimes using the “shorthand” system. (The same was true of interviews, in jazz magazines and elsewhere.) You can be certain that they worked from notes, and not from tapes, because they came up with slightly different versions of what Dr. King said. For example, the Times wrote that he said “Good still has a way of growing out of evil,” whereas Harwell wrote, “God still has a way of bringing good out of evil.” But what Dr. King actually said, according to his typescript, is: “God still has a way of wringing good out of evil.” Here is Harwell’s article:

This appeared in many papers that used the AP service, but I chose to reproduce this one from High Point, North Carolina, the city where Coltrane grew up; his family moved there when he was an infant. Harwell had written a few more paragraphs at the end, describing the funeral, but not all papers included that part, and anyway that part had no quotations from Dr. King, so I have omitted it.

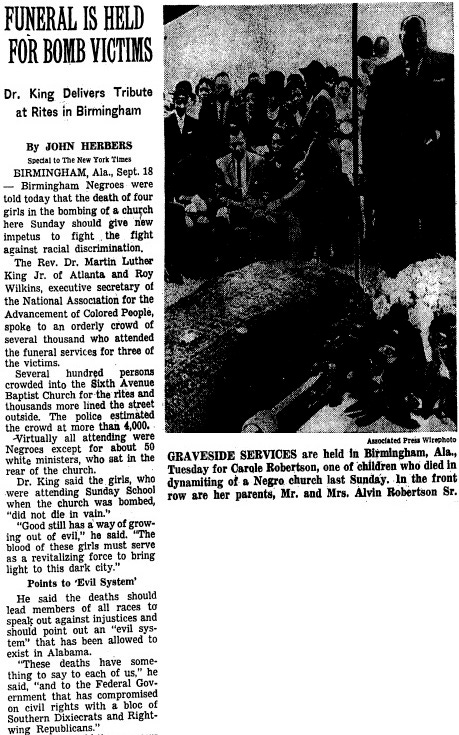

Now, let’s see the Times article and compare it with Harwell’s story. To save space, I cut out the last few paragraphs because they have no quotes from King

As you can see, the Times only had a few sentences from Dr. King. I’m basing my analysis below on Harwell’s article because, even though Coltrane probably saw the Times, it did not have as much of Dr. King’s speech. But Coltrane moved around so much that he could easily have seen one of the hundreds of papers that carried Harwell’s piece. As mentioned above, he was in Buffalo on the day of the bombing. Between that day and the recording, he performed in Cleveland and New York City, toured Europe, and performed in Philadelphia. Admittedly, we don’t know which newspapers he saw, but in those two months he also had two separate weeks off, and I’m willing to bet that he came across Harwell’s article while traveling or while at home in New York—in Manhattan then and now, there were shops that sold out-of-town newspapers—or a friend showed it to him or even mailed it to him.

If I’m right, this and only this article — not a complete transcript, not an audio recording — is what Coltrane had access to in the two months between the funeral on September 18 and the recording of “Alabama” on November 18. So what does this say about the claim that Coltrane based “Alabama” on Dr. King’s words? Well, there is surely enough there to work with, and he had two months to think about it, to work on it, and to organize the excerpts.

So I began to listen again, and this time I immediately heard Coltrane start by saying: “They did not die in vain.” Listen again:

As I continued to listen with fresh ears, I thought I heard him moving around to different parts of the article, and even repeating some phrases. I also heard him adding notes at the ends of some phrases.

All of this should not be a surprise. After all, this was very likely the first time that he set words to a saxophone line. “Song of Praise,” “The Drum Thing,” and A Love Supreme were all to come later, in 1964. And “Alabama” may be the only time that he used someone else’s words — as far as we know, from this point on, whenever he used words to help compose a piece, they were words that he wrote himself. And he only had these isolated quotes, not the full text of the speech, so it was up to him to make them into something coherent.

I’m not yet certain how he rearranged the words. I have not managed to fit the words to every phrase in the music. It seems to me that, unlike “Psalm,” he might be embellishing some words with extra notes. But here’s what I have so far (words in parentheses are not played):

They did not die in vain. 0:05: God still has a way (of) bringing good (longer note for “good”) out of evil — they did not die in vain. 0:15: (The) innocent blood of these little girls may well serve as a redemptive (low notes) force for this city (a few extra notes here). 0:30: We must not despair (extra notes on “despair”), we must not become bitter:

(I haven’t been able to fit words for 0:42 to 1:20 yet.)

1:20: (Softly, mournfully — the band goes along with the rhythm that he conducts with his head) Today you do not walk alone— 1:34: Not walk alone:

On most releases, this is followed by the improvisation, marked by Garrison’s walking bass.

After the saxophone solo, the entire recitation is repeated, but this time after “Not walk alone,” I hear Coltrane exclaim the following, slowly, each word drawn out, and screaming with passion on the last high notes:

They did not die – they did not die in VAIN….IN VAIN…

(This is followed by a cascade of improvised notes, and the second “In Vain” is not played on the televised performance.)

There’s real power to this music. Coltrane is in full preaching mode. That ending, especially now that I hear the words, makes my scalp tingle and my heart race. It makes me shake my fist, and I imagine Coltrane doing the same when he created this piece.

As for the rest of the words, that’s as far as I’ve gotten at the moment. None of the other lines of the text fit so well to the music as the ones I’ve just shared with you. And of course, it’s possible that John added some words of his own, or slightly reworded things.

Because it’s difficult to fit the melody to the words, some people have said to me, “Maybe it’s not a syllabic setting — maybe it’s a vague impression of Dr. King’s speech. Maybe that’s why it’s hard to match it to the words.” But that makes no sense, because there’s nothing vague about the music. For just one example, notice that the first phrase—the first audio example at the top of this page— ends with the note C three times (at 0:12). On the TV performance clip above, he does the same (at 0:30). Why exactly three Cs? If it’s a vague impression, why not be more free, play whatever you feel like? According to my analysis above, the three Cs say “die in vain.” That’s why there have to be exactly three.

Moving on, the third and fourth phrases are entirely composed of the notes Bb, C, D and Eb, played up and down, in and out, with C repeated at the end. Playing in this extremely limited range is not singing a “tune”; it’s chanting, unmistakably. And if it were just a vague impression, why not embellish it, add a note here and there, as he always did on every ballad he ever played? Remember, he plays it the same way after the improvisation with walking bass. I’m certain that Coltrane is chanting a text here, even though I haven’t fully figured it out yet.

I hope you can live with this unfinished decoding of “Alabama.” You can be sure that I’ll continue to think about and research this profound piece of music.

But wait—in your collection, and online, you will probably find that “Alabama” is about 5 minutes long. But on some releases it’s 2 and-a-half minutes long, with no middle section of walking bass and improvisation. What happened? Well, in the third and final essay of this series, we’ll look at how the piece was edited, spliced, and released. And we’ll listen to a number of “cover” versions—including one by Dave Liebman, Marc Ribot, and myself. I’m working on that essay now, and until it’s ready I’ll be posting on other topics, as always.

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. A different version of this essay was originally posted at WBGO.org in 2020. For their help with that post, I would like to thank my editor there, Nate Chinen, and the following kind people: Meghan Weaver, Research Assistant at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project at Stanford University; Steve Rowland, co-producer (with Larry Abrams) of the award-winning 5-hour radio series Tell Me How Long Trane’s Been Gone; and Medd Typ Persson for our online discussion.

Wow, such a powerful read.

The first time I became aware of this type of composition technique was as a student of Dr. Billy Taylor.

“I wish I knew how it would feel to be free“ made famous by Nina Simone was composed in a similar fashion from a phrase Billy wrote to demonstrate gospel style to his young daughter.

Billy visited the African-American Studies department at UMass two or three times a year and I remember him demonstrating on piano how he composed a melody to match the text of a statement Dr. King made.

I look forward to discussing this topic with Lewis further as I have been developing an idea about some of the music and musicians at Woodstock, including Star-Spangled Banner by Jimi Hendrix, as directly coming from this mold cast by Coltrane.

i am totally spellbound by this, how you've pieced so much of the song to King's words, Bravo!