Today, and in the next two posts, you and I will celebrate the New Year by enjoying some music that was recorded at a private home jam session on May 30, 1942, but was only recently discovered. It’s always great to hear more Tatum, and this find is especially exciting because, though most people today don’t know it, Nat “King” Cole was a famous and influential jazz pianist before he ever recorded as a singer. He had been inspired by Tatum, Teddy Wilson, Earl Hines, and others, but his style was distinctive and very recognizable. He takes a terrific piano solo on one of these discovered tracks. And on one song he is playing bass!

When I tell people that Cole was a pianist, they often reply, “Oh, sure, lots of singers play a little piano, to accompany themselves and so on.” No, no, no!—Cole was not a “competent” player. He was a superb soloist, and widely admired. Here he is on an early Jazz at the Philharmonic concert, July 30, 1944, improvising on “Tea for Two.” If you’ve heard him play before, sit back and enjoy. If you haven’t, prepare to have your mind blown!

What creativity and wit, and what a variety of approaches! What irresistible swing, and what mastery of the instrument! And if he makes you think at all of Oscar Peterson, please know that Oscar explicitly acknowledged Nat’s huge influence on him—as did hundreds of other pianists. About half of Will Friedwald’s major Cole biography is devoted to Cole’s career as a pianist.

Now, to the new discoveries. People often wonder, how can it be that previously unknown recordings of legendary jazz artists like these can continue to turn up, so many years later? After all, it’s only in recent times that people can take out their cell phones and record anything on the spur of the moment. The simplest answer is that, way before cell phones, and years before tape recording was available in the late 1940s, portable recording machines allowed people to record on 78 r.p.m. discs, both at home (for “live” music and radio broadcasts) and at performances. Often, the person who had the recordings left them in a closet, and eventually forgot about them. Many years later, these items are found by a family member and donated, sold, or auctioned off (these days, most commonly on eBay). In fact, the recordings you’ll hear in these two posts were sold by someone who knew nothing about them except that they were among his late father’s possessions.

These three posts are especially remarkable because of an amazing coincidence: Jazz historian Steven Lasker purchased two discs on eBay containing previously unknown recordings of Tatum and Cole. That is great news in itself. But then he notified film expert Mark Cantor, who realized that he has silent home movies in color from this very occasion! He has the original films, not copies, and we will see photo stills from them. Unbelievable!

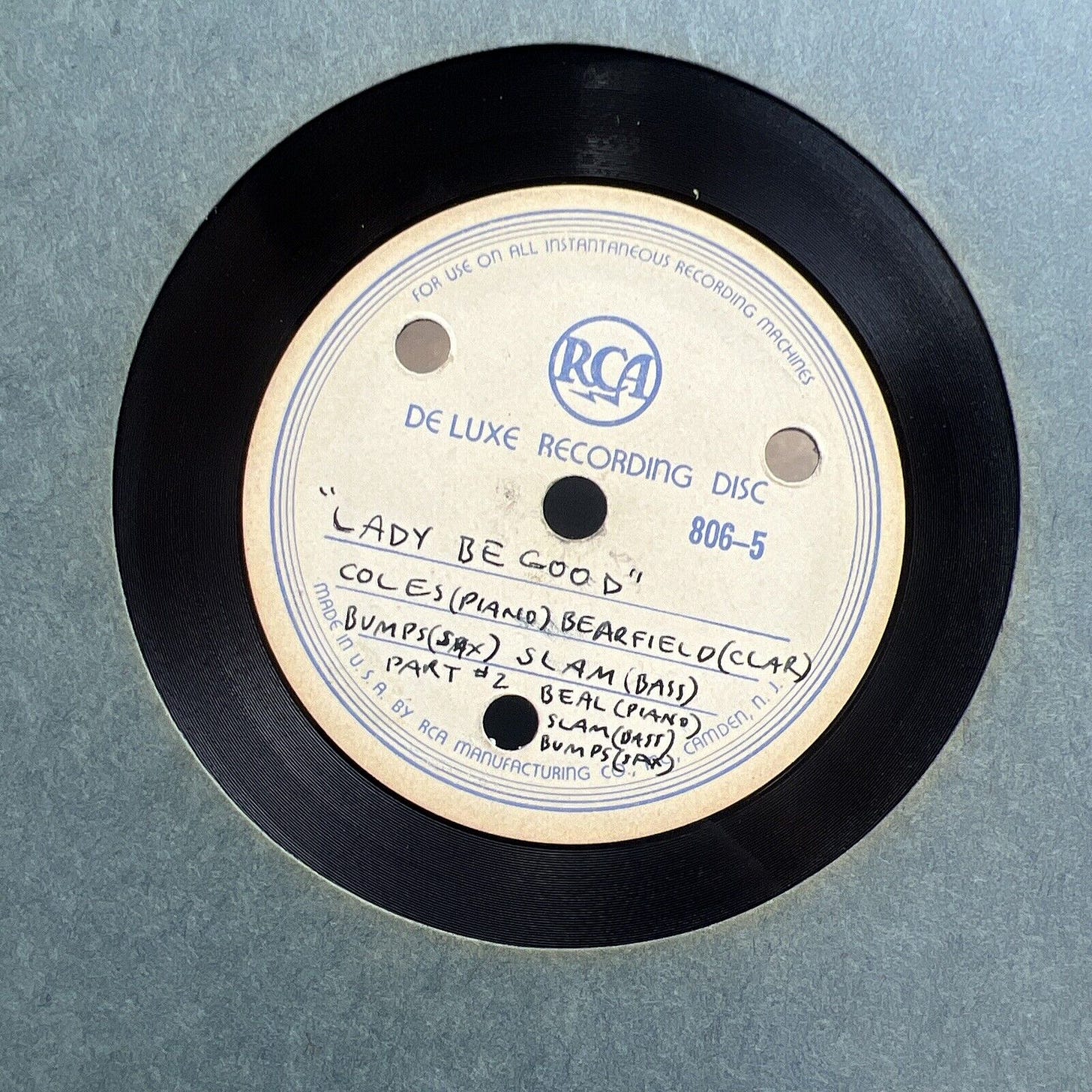

There is no way to know the sequence in which these tunes were recorded, so I’m simply presenting them in an order that works for this story. Today you will hear two tunes from one of these discs. In the next two essays we’ll hear the rest. First, here is a photo that shows a complete disc, so you can see what they looked like. One could buy blank discs back then—in this case, from the RCA company—just as, in recent years, we bought blank CDs. A standard commercial 78-rpm record was 10 inches in diameter, with room for about three to three and-a-half minutes of audio, but larger sizes were made for various purposes. These two discs were both 12 inches, and could hold about four to five minutes on each side:

Here are stills from the home movies. On the left you can see the recording machine used that day. Next to that is a still of Nat reading a magazine, likely one of the music magazines:

Now, let’s look at the handwritten label that tells us what music is on one side of this home recording:

“Lady Be Good” (the Gershwins titled it “Oh, Lady Be Good”) features “Coles”—Nat Cole, that is—on piano, with “Bearfield”—actually Eddie Barefield—on clarinet, “Bumps” Myers on tenor sax, and Leroy “Slam” Stewart on bass. (The label also refers to a Part #2. That’s a short separate recording which we’ll hear next time. When there was space left, one could come back and record more on that side, just as one might fill up unused space on a recordable CD.)

Of the artists listed, you’re probably most familiar with Slam Stewart (1914-87), one of the outstanding bassists in jazz history. Barefield (1909-1991) was an accomplished clarinetist, saxophonist, and arranger. He was strongly associated with Cab Calloway, but also worked with many other top Black big bands. He had met Tatum about 10 years earlier in Art’s hometown of Toledo, Ohio, so they were old acquaintances. Myers (1912-1968) was a warm-toned player who was based in the Los Angeles area. At the time of this 1942 session, he was playing alongside Lester Young in a two-tenor band led by Lester’s younger brother, drummer Lee Young. He toured with Benny Carter’s big band in the mid-1940s. Fans and critics raved about Myers’ playing. (His birth name was Hubert—I don’t know where he got his nickname “Bumps.”)

So let’s listen to “Oh, Lady Be Good,” which begins in progress with Barefield’s clarinet on the bridge of a chorus, backed up by Cole and Stewart. His style is very melodic, almost like the way Pres sounded on clarinet—they had known each other since the late 1920s. Cole solos at 1:25, and he is terrific—full of ideas! I love that line in his second A section at 1:35 that kind of echoes the bass. Stewart is “slapping” the bass here, which some say is why he became known as “Slam.” (But there are other stories about his name as well.) Nat ends his solo with some dissonant chords at 3:10, and it sounds as though Slam is starting to solo, but he quickly goes back to walking when Myers comes in. The recording ends during his expressive tenor saxophone solo. Enjoy!:

(The original disc was a bit off-speed, putting it above the usual key of G. A Big Thank You to clarinetists/saxophonists Aaron Johnson and Kenny Berger who confirmed that the musicians at the jam were playing in G by studying Barefield’s playing. And another “shout out” to Steven Lasker for the transfer and restoration of all of the tracks for this series of three essays, and to guitarist and jazz historian Nick Rossi for doing additional work on pitch, volume and more.)

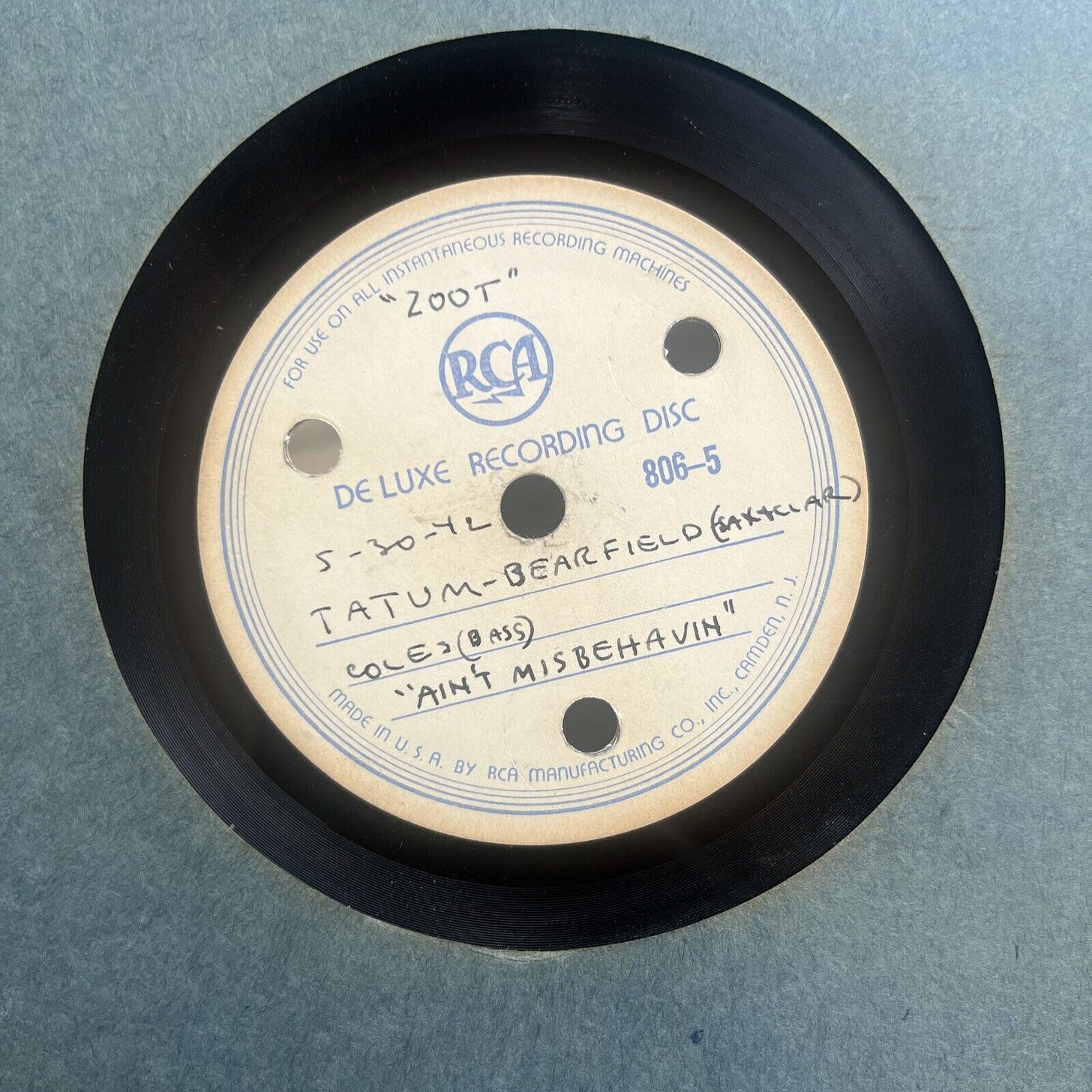

The other side’s label, below, says “Zoot” on top, an expression usually referring to hip fashion back then, but here just meaning “hip!” Then it provides the necessary information: The date is confirmed to be May 30, 1942. That was a Saturday, and these artists had gigs to go to, so it must have been during the daytime. The song is Fats Waller’s “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” And the performers are Tatum, Barefield on sax and clarinet, and “Coles” on bass.

Wait a second! That can only mean Nat “King” Cole on bass, because he was the only “Coles” there that day! As you will hear, there are more reasons to believe that it is indeed Nat on bass.

So let‘s listen to this side. It begins with the white hosts—we will identify them next time—joking around, while Barefield plays clarinet. There are I think two men and a woman, singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas”—a very popular new song at that time—and talking about Texas and the United States, and so on. Cole plays a little bass in the background. After more conversation, Tatum launches into “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and Barefield and Cole join in. The hosts continue to talk, and sing along a bit during the performance. Someone whistles at 2:22, sings at 3:28, and so on.

During the first chorus the bassist plays a “two feel,” but starting at 1:40 he “walks” by playing each note twice. (That is in fact how bassists first walked—the subject of another essay.) Now, here’s the other reason we know that it’s Nat Cole on bass—besides the label, which is proof enough: At that moment, impressed at how well the pianist is doing on the bass, someone says “Sweet notes of Nat Blanton.” The joke, of course, is that the speaker is purposely exaggerating by comparing Cole to the then-new bass sensation of Ellington’s band, Jimmie Blanton. In fact, Cole is doing just OK—he’s no Blanton—but everybody’s having fun.

Tatum is in the mood to play melodic right-hand lines, for example starting at 1:40 (just before the Blanton joke), and for his solo starting at 2:40. He’s staying within the chords here (as I’ve shown in five essays to date, he often played “way out”), although he does get a little adventurous at 3:28. After him, that’s Barefield on tenor sax at 3:45. The disc runs out at the end of a chorus, but it sounds like they kept on playing. ENJOY!:

Now, how is it that Cole could play bass? Well, his brother Eddie, almost 9 years older, was a bassist. Nat made his first recordings with him in 1936. So there was a bass—and a bassist—in the house. And when someone is good on one instrument they usually find that it’s fairly easy to pick up another one, just to play it a little bit. (To become equally good on the other instrument is another story, although of course many people have done that—Benny Carter, Ira Sullivan, and so on.) And, to be honest, he doesn’t sound amazing on the bass. He’s not perfectly in tune, and his fingers aren’t strong enough to get much of a tone. For example, listen to this excerpt of the above recording of “Misbehavin’” (I started at 2:25):

Now, compare that with Stewart’s strong sound and beat throughout “Lady” above. But it’s great fun, and Cole’s musicality carries him through.

But why is Cole playing bass? Well, with Tatum having taken over the piano, he surely wanted to find some way to participate. Maybe Slam was out of the room at the moment, or maybe he simply agreed for Nat to play his bass. Although it’s never been mentioned anywhere that Cole could play bass, this was clearly not his first time.

We’ve still got three more pieces to hear from this amazing discovery! And a lot more background information, plus photos, news clippings, and more. Coming soon!

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Special thanks to Steven Lasker, Mark Cantor, and Nick Rossi for help with this essay.

P.P.S. To inquire about professional use of the home movies mentioned, contact jazz film expert Mark Cantor, whose collection is one of the world’s largest, at: markcantor@aol.com

You are also encouraged to visit his site, where he posts rare clips and film research.

WOW!!!

Congrats to the whole team for sharing this new and intriguing music with the world!! That Nat chorus on LBG is unlike anything else I’ve heard from him before.