(Paying Subscribers, below you’ll find an article about the scene of this jam session.)

This is the second of three essays (and of course I wrote much more about Tatum last year). Let’s continue exploring this amazing discovery of new music from Art Tatum, Nat “King” Cole, Slam Stewart, Eddie Barefield, and others. Last time I gave you some general background, and we heard two tracks.

The jam session was hosted by Andy and Mary Mackay, a white couple who befriended many Black jazz artists. They lived a mile or so southeast of the Los Angeles airport. They took 8-millimeter silent color films of this day, and at other times they made black-and-white silent films of significant L.A. jazz events—including Ellington’s show Jump for Joy! Here are two still photos from the jam session footage, to add to the two that you saw last time:

From the left, you see Slam Stewart, Bumps Myers, Eddie Barefield, and Tatum. The separate still on the right is pianist Eddie Beal, next to the light used for taking films, with Mary Mackay in the shadow. Beal figures in our story soon. (Paying Subscribers, for more about the Mackays, and more photos, scroll down.)

As you saw last time, the date handwritten on one of the home-recorded discs is May 30, 1942. Guitarist and jazz historian Nick Rossi double-checked that date in the local newspapers and he found that it definitely makes sense: Tatum was in Hollywood all month at a club called, believe it or not, Streets of Paris. Eddie Barefield had been in town since mid-May leading Ella Fitzgerald’s orchestra at the Trianon in nearby South Gate. (Here are addresses for these clubs from the 1947 phone book’s “Yellow Pages.”) Nat Cole’s trio had just begun what would turn out to be a long and career-building engagement at the 331 Club. (See Will Friedwald’s biography.) And as you can see in these clippings from the May 21, 1942 issue of the California Eagle, a Black newspaper, Billie Holiday was also in town:

These are from the regular music news column, Swingtime in H’wood by Freddy Doyle. Beal (1910-1984; not “Beale”) was, as noted in the piece, a well-respected member of the Los Angeles music scene, and spent his entire career there. (His older brother Charlie Beal was more widely known because of his international touring with Louis Armstrong and others.) He was a favorite accompanist of many singers, such as Herb Jeffries and later the young Lou Rawls, so it makes sense that he was working with Billie. You will be very interested to know that Holiday and Beal were part of a bill that also included a septet led by drummer Lee Young that featured his older brother Lester, Billie’s favorite, with Bumps Myers as the other tenor saxophonist. When Holiday and Beal were performing, Lester, and other members of the Young group, often played with them. (A few numbers from radio broadcasts exist. Although Jimmy Rowles was the Youngs’ regular pianist, it’s probable that Beal played behind her.) Slam Stewart was also on the bill, as half of the popular “Slim and Slam” duo with singer, entertainer, pianist, guitarist Slim Gaillard.

Beal was a good friend of Tatum, who had moved to L.A. in 1936—he was later a pall bearer at Art’s funeral—and he knew Cole, who settled there a year later. Beal remembered them both in an interview with L.A.’s Black music historian Bette Yarbrough Cox in 1983. Here are two relevant short excerpts:

So Stewart, Beal, Barefield, Myers, Cole and Tatum were all friends and were all gigging in L.A., when they accepted an invitation to come to the home of the Mackays. There was at least one other musician, as we’ll see next time. And there were probably a few friends in addition—on the recordings last time we heard the voices of at least three people. And now, I know you’re dying to hear the rest of the music. Okay!:

We didn’t get to hear the short piece at the end of one side of the disc from last time. It’s an incomplete performance of “Moonglow” (written this way on the sheet music, but sometimes written as two words). It’s a performance by Slam, in his trademark bowed and sung style, accompanied by Beal in a double-time feel (one-and-two-and etc.). Here goes:

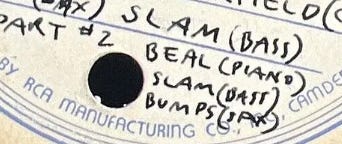

As you may recall, from the previous post the writing on the label said that Myers also played, but he’s not on the recording:

Probably he played just as the disc ran out, and the person writing on the label didn’t realize that the saxophone solo hadn’t been captured.

Around this time, Tatum said that Slam and the recently deceased Jimmie (that’s the correct spelling) Blanton were his favorite bassists. Art and Jimmie had even played together. (Downbeat reported in its issue of June 1, 1940 that they had recently jammed all night.) So it’s no coincidence that soon after this jam session, Slam and his guitarist Tiny Grimes became members of Tatum’s first Nat Cole-style trio. And “Moonglow” was in their repertoire. Here’s what Tatum said in the California Eagle, August 6, 1942:

Now let’s move on to the two sides of the other disc. This disc appears to have been a gift from the Mackays to friends. On one label they wrote “Dig This! Tatum & Slam”:

The duo performs the popular song, ”I Surrender Dear.” It’s a leisurely, extended performance by Art. He goes “way out” from 1:22-1:30, and a bit “out” at 2:50. Here are those moments:

During a particularly swinging passage starting at 3:50, you’ll hear the onlookers respond with pleasure. Slam solos after Art, and the disc ends in the second A section, just after he quotes the bridge of “Lover, Come Back to Me.” Please note, there’s a skip in the disc itself at 1:30, and I thank Nick Rossi for editing this so that the disturbance is as slight as possible. Here is this complete never-before heard performance:

There’s one more track. But there is so much to say about it, that it requires a post of its own. Coming soon!

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Special thanks to Steven Lasker, Mark Cantor, and Nick Rossi for help with this essay. I also thank Steven Lasker for the transfer and restoration of all of the tracks for this series of three essays, and to guitarist and jazz historian Nick Rossi for doing additional work on pitch, volume and more.

P.P.S. To inquire about professional use of the home movies mentioned, contact jazz film expert Mark Cantor, whose collection is one of the world’s largest, at: markcantor@aol.com

You are also encouraged to visit his site, where he posts rare clips and film research.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.