Frederick Douglass Writes About Minstrelsy, +Bonus

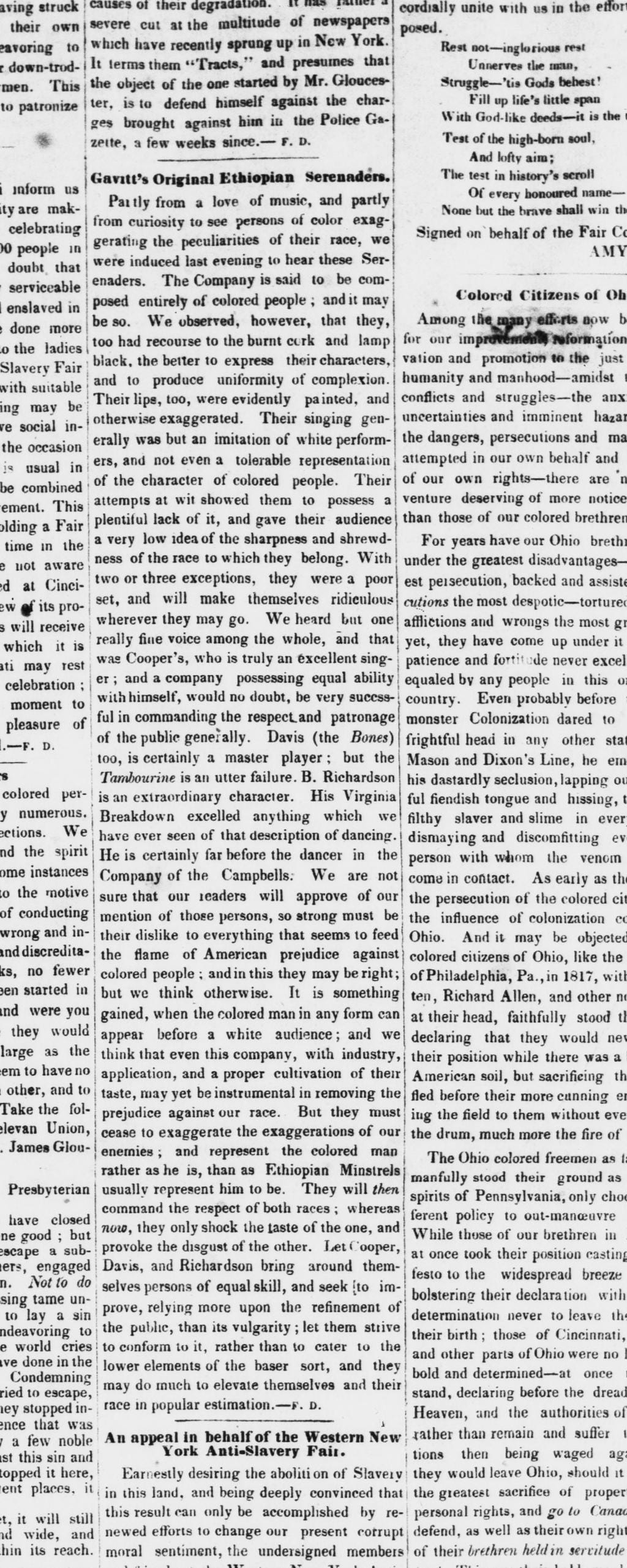

Paying Subscribers, you can see the original newspaper page at the very bottom.

As everyone knows, Frederick Douglass (ca.1818-1895) was brilliant. Here’s one piece of evidence, among many: Pick up his autobiography (any edition—he enlarged it twice as he got older—and they’re all online) and try to stop reading after the first page. You can’t stop, because his writing is riveting. He sees things with clarity and honesty, and his writing style is masterful.

Douglass lived in the era of the blackface minstrel show. Minstrelsy has one of the most complicated legacies in American culture. There is a direct line from the blackface minstrel shows, which began in New York City, Boston and elsewhere around the late 1830s—

To the “vaudeville” shows (a term I’ve seen in American newspapers as early as 1837 to refer to French entertainments, and later to American ones) or “variety” shows (so-called because each show was comprised of a variety of independent short acts by comedians, dancers, jugglers, and so forth) later in the 1800s and into the 1900s—

To the variety shows on radio in the 1940s and then television in the 1950s. (Ed Sullivan was one of many hosts who went from radio to TV, and the shows were still a succession of unrelated acts—in 1964, the Beatles were followed by a magician, for example.)—

And from there to the late night shows of today.

Obviously, the legacy of minstrelsy also extends deeply into the history of jazz. When one reads about Lester Young and Ma Rainey and other early Black musicians playing with a touring show, one mustn’t be so naive as to imagine that they were giving concerts. They were generally part of a variety or minstrel show, and often they accompanied blackface performers. For example, in the Young family show of the 1920s, the musicians did not wear blackface, but the Black entertainers did. In the early 1900s, Ma Rainey toured with a show that featured “Black Face Song and Dance Comedians, Jubilee Singers [and] Cake Walkers” (that is, dancers who did the cakewalk). And there are many other Black musicians who spent early years in minstrel shows, although that is rarely discussed.

Minstrel shows had a fairly set program which included comedy, dancing and singing. Even in entertainments that never used blackface, the jokes from minstrel shows remained popular. Much of the humor in the children’s program Kenan and Kel, which ran from 1996 to 2000, came right out of the old minstrel shows. And although the practice of blackface died out in most American arenas by the late 1940s, it still crops up now and then here and overseas, especially in the often stubbornly traditionalist world of opera. The Metropolitan Opera in Manhattan only stopped using blackface in 2015! And as recently as July 2022, Angel Blue learned with dismay that blackface was still being practiced in the famous opera house at Verona, Italy.

When viewers today see old movies that employ blackface, they are appalled and disgusted. Yet, it’s hard to believe, but important to know, that right into the 1940s, most white audience members didn’t think twice about seeing performers in blackface. Even such big stars as Judy Garland, Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire appeared in movies in blackface without any significant outcry from their many white fans.

To make things more complicated—and this is important—most of the white participants in blackface entertainments felt themselves to be sympathetic to Black people. They did not consciously hate Blacks, and did not “get” that their roles were insulting to Black people. After all, they were, as they saw it, writing and performing comedy, not hate speech. None of them ever thought that an evening of hate speech would make good comedy. And the minstrel shows were inspired by some white people’s observations, however superficial, of Black songs, dances, and wit, which many whites claimed to be “authentic.” But Black citizens continued to protest, and the Black press and the N.A.A.C.P. regularly spoke out against the practice, and that is why after the late 1940s blackface finally became less and less common, and less acceptable even among white audiences.

Douglass saw right through all of this complexity, right from the early days of minstrelsy. In his writings, he exposes all the hypocrisy of it. Let’s read one of his short essays on the topic, and then go over it line by line. Here is the text, as it was published in his own newspaper, The North Star, in Rochester, New York in 1849:

The North Star

29 June 1849

Gavitt's Original Ethiopian Serenaders.

Partly from a love of music, and partly from curiosity to see persons of color exaggerating the peculiarities of their race, we were induced last evening to hear these Serenaders. The Company is said to be composed entirely of colored people, and it may be so. We observed, however, that they too had recourse to the burnt cork and lamp black, the better to express their characters and to produce uniformity of complexion. Their lips, too, were evidently painted, and otherwise exaggerated. Their singing generally was but an imitation of white performers, and not even a tolerable representation of the character of colored people. Their attempts at wit showed them to possess a plentiful lack of it, and gave their audience a very low idea of the shrewdness and sharpness of the race to which they belong. With two or three exceptions, they were a poor set, and will make themselves ridiculous wherever they go. We heard but one really fine voice among the whole, and that was Cooper's, who is truly an excellent singer; and a company possessing equal ability with himself, would no doubt, be very successful in commanding the respect and patronage of the public generally. Davis (the Bones ) too, is certainly a master player; but the Tambourine was an utter failure. B. Richardson is an extraordinary character. His Virginia Breakdown excelled anything which we have ever seen of that description of dancing. He is certainly far before the dancer in the Company of the Campbells. We are not sure that our readers will approve of our mention of those persons, so strong must be their dislike of everything that seems to feed the flame of American prejudice against colored people; and in this they may be right, but we think otherwise. It is something gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience; and we think that even this company, with industry, application, and a proper cultivation of their taste, may yet be instrumental in removing the prejudice against our race. But they must cease to exaggerate the exaggerations of our enemies; and represent the colored man rather as he is, than as Ethiopian Minstrels usually represent him to be. They will then command the respect of both races; whereas now they only shock the taste of the one, and provoke the disgust of the other. Let Cooper, Davis and Richardson bring around themselves persons of equal skill, and seek to improve, relying more upon the refinement of the public, than its vulgarity; let them strive to conform to it, rather than to cater to the lower elements of the baser sort, and they may do much to elevate themselves and their race in popular estimation.-- F. D

Here’s what it looked like in print, on page 2 of this 4-page weekly newspaper.

(Paying Subscribers, you can see the original newspaper page at the very bottom. The page includes other very interesting articles, such as Douglass’s critique of other Black newspapers.)

This is worth discussing in detail, because just about every line is packed with insight and information:

“Partly from a love of music, and partly from curiosity to see persons of color exaggerating the peculiarities of their race, we were induced last evening to hear these Serenaders.” First of all, please correct all the books and encyclopedias you have read that say that Black people first performed minstrel shows after the Civil War. This is 1849! Still, it was relatively rare then, which is why Douglass says he was curious to see “persons of color” in a minstrel show. In other words, he had never seen Black people in a minstrel show before. He was “induced” to go—that is, he had to overcome some resistance to it—but he decided, perhaps through someone else’s arguments, to go because of curiosity and because of “a love of music.” Minstrel shows were, after all, evenings of music and comedy, and many hit songs started in such shows. Also, please note that here and in the discussion that follows it is clear that the audience was mostly white, but was integrated. Despite what you will hear or read about the North being “as bad as the South,” integrated audiences were common in most Northern cities, and not in the South. And in most other ways, it is not at all fair or accurate to think that life in the Northern states was anything as bad as being a Black person in the South, even a free Black.

The word “Ethiopian” in olden times (roughly between about 1600—Shakespeare’s day—and 1900) was a way of referring to anybody who was dark-skinned. You may be certain that the members of this troupe were not actually from Ethiopia! But the word was also used by whites pretending to be Black performers. A well-known blackface white group called itself The Ethiopian Serenaders (sometimes known as the Boston Minstrels) in the 1840s and 1850s.

Finally, in this opening sentence Douglass defines minstrelsy, as a show that exaggerates “the peculiarities” of Black people. At that time, “peculiarities” did not indicate something weird, but only the distinctive and unique qualities of a person or group. In other words, the minstrels took qualities that they considered to be partly valid as a generalization about some Black people, but exaggerated them until they became silly and laughable caricatures.

“The Company is said to be composed entirely of colored people, and it may be so. We observed, however, that they too had recourse to the burnt cork and lamp black, the better to express their characters and to produce uniformity of complexion. Their lips, too, were evidently painted, and otherwise exaggerated.” He’s telling you that you wouldn’t know by looking at them that they were an all-Black theater troupe, because the black makeup (from burnt cork and oily “lamp black”) covered their faces just as in white troupes. He’s also telling you that the makeup was not simply intended to make white people look black. It was a kind of mask, that produced a “uniform complexion,” and that helped to define the different characters. In minstrel shows, there were certain standard characters that audiences had become accustomed to seeing. The exaggerated lips was part of that too—they were, he notes, “evidently painted.” That is, it was clear and evident that they were painted.

Next he reviews the performance. Here I’ll paraphrase: Their singing was an imitation of white performers, rather than a representation of the way Black people sang. Their jokes weren’t funny, and the audience would never know from this performance that Black people are actually very shrewd and sharp. Douglass loved Black culture, and he hated to see it demeaned. He will say more in a minute about the need to represent it faithfully on stage.

With two or three exceptions, Douglass goes on, the performers were pretty much ridiculous. Among the exceptions was Cooper, who is truly an excellent singer; and would sound great in a company of people at his level. Davis, who plays the standard character Bones, is a master player of the Bones (percussion, played originally with bones). And B. Richardson danced the best Virginia Breakdown that Douglass had ever seen. In the rather set program of minstrelsy, the Bones and the Virginia Breakdown—or some such dance in “the Negro style”—were expected parts of every program. And Douglass is letting you know that he has seen minstrel shows before, by white performers—as most people across America had by then.

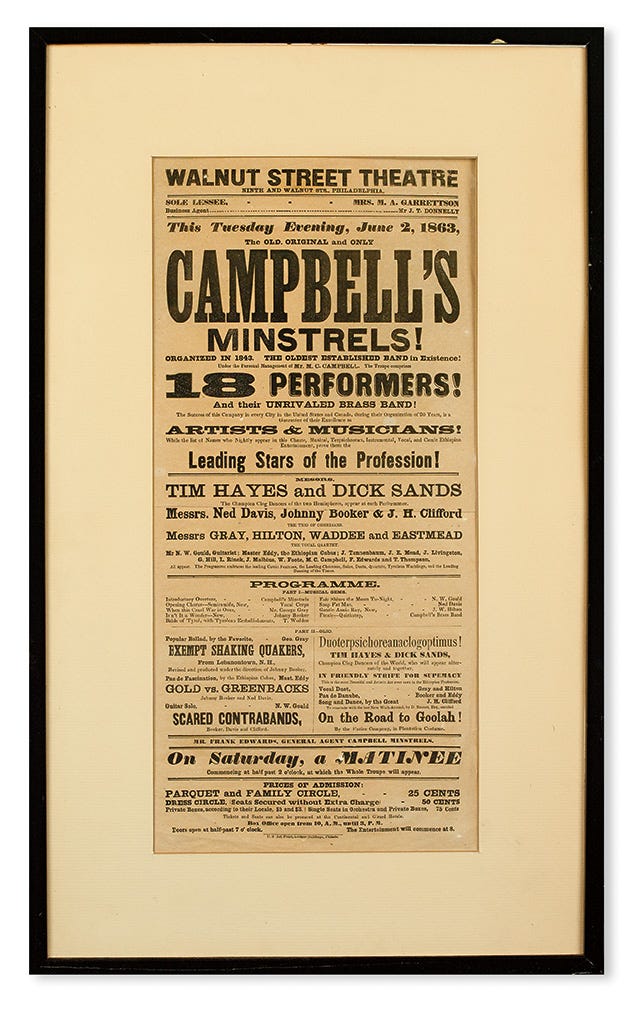

Douglass makes a point to say, “He is certainly far before”—far better than—” the dancer in the Company of the Campbells.” The Campbells, founded in 1843, was a famous white minstrel troupe, so this is is a significant compliment. Here is a poster announcing one of their performances in 1863 in Philadelphia (sorry about the low resolution):

Douglass goes on to say “We are not sure that our readers will approve of our mention of those persons, so strong must be their dislike of everything that seems to feed the flame of American prejudice against colored people.” Remember, his readers were absolutely pro-Black and against slavery. But, he goes on, “we think otherwise.” That is, he thinks that comparing this black troupe to the white one is actually the key. Because, “It is something gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience.” This is an unusual opportunity for Black people to appear before white audiences. Other than in minstrel shows, in what context did whites see Black people perform in those days, whether in the North or the South? (Most Black non-minstrel groups came later. For example, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers were founded in 1871.) He believes that if companies like this worked hard to present really high-level shows, they “may yet be instrumental in removing the prejudice against our race.” But—and this is crucial—”they must cease to exaggerate the exaggerations of our enemies.”

Notice that he uses the word “enemies” to refer to those whites who have a low opinion of Black people. He always spoke and wrote frankly, and didn’t soften the truth. In his newspaper in 1848, he had described white blackface minstrels as “the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow-citizens.” He made his feelings known!

Black minstrels, he argued, should aim to “represent the colored man rather as he is.” Remember, the minstrel shows were partly inspired by certain aspects of Black culture. They were not invented out of thin air. The humor relied on familiarity, on the fact that most whites had some experiences of seeing Black people sing, dance and joke. The shows offered exaggerated caricatures of certain folkloric realities. So Douglass suggests, let us remove the exaggerations. If Blacks present high-quality shows, “They will then command the respect of both races; whereas now they only shock the taste of the one”—white people—”and provoke the disgust of the other”—Black people who are being lampooned and made fun of. The Black troupes should aim to refine the taste of the white public, rather than catering to their lowest (“vulgar”) taste just to become popular.

Douglass, in his brilliance, saw right through minstrelsy, and beyond. He understood that many audience members, Blacks as well as sympathetic whites, would find these shows offensive. But, he said—and this is the “takeaway”: Let’s get past our gut reaction. White people want to be entertained by Black songs, dances, and humor. In that case, let us Blacks not copy the silly and embarrassing material that has made white troupes successful. Instead, let Black entertainers look at this as an opportunity to show white audiences the very best of Black music, dance and wit. In this way, he concludes, “they may do much to elevate themselves and their race” in the view of white people.

Deep stuff, indeed!

All the best,

Lewis

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.