Gene Krupa Deserves A Close Hearing (+ Paying Subscribers' Bonus)

And a note about bassist Thelma Terry

(Note: Paying subscribers, as usual your bonus is at the very bottom—a complete magazine.)

It seems funny that I feel compelled to write an essay “defending” Gene Krupa, since he was one of the most popular drummers of all time. You might say that he doesn’t need my help. But he is one of those jazz artists whose reputation in the jazz community—that is, among fans, critics, and musicians—is far lower than among the general public.

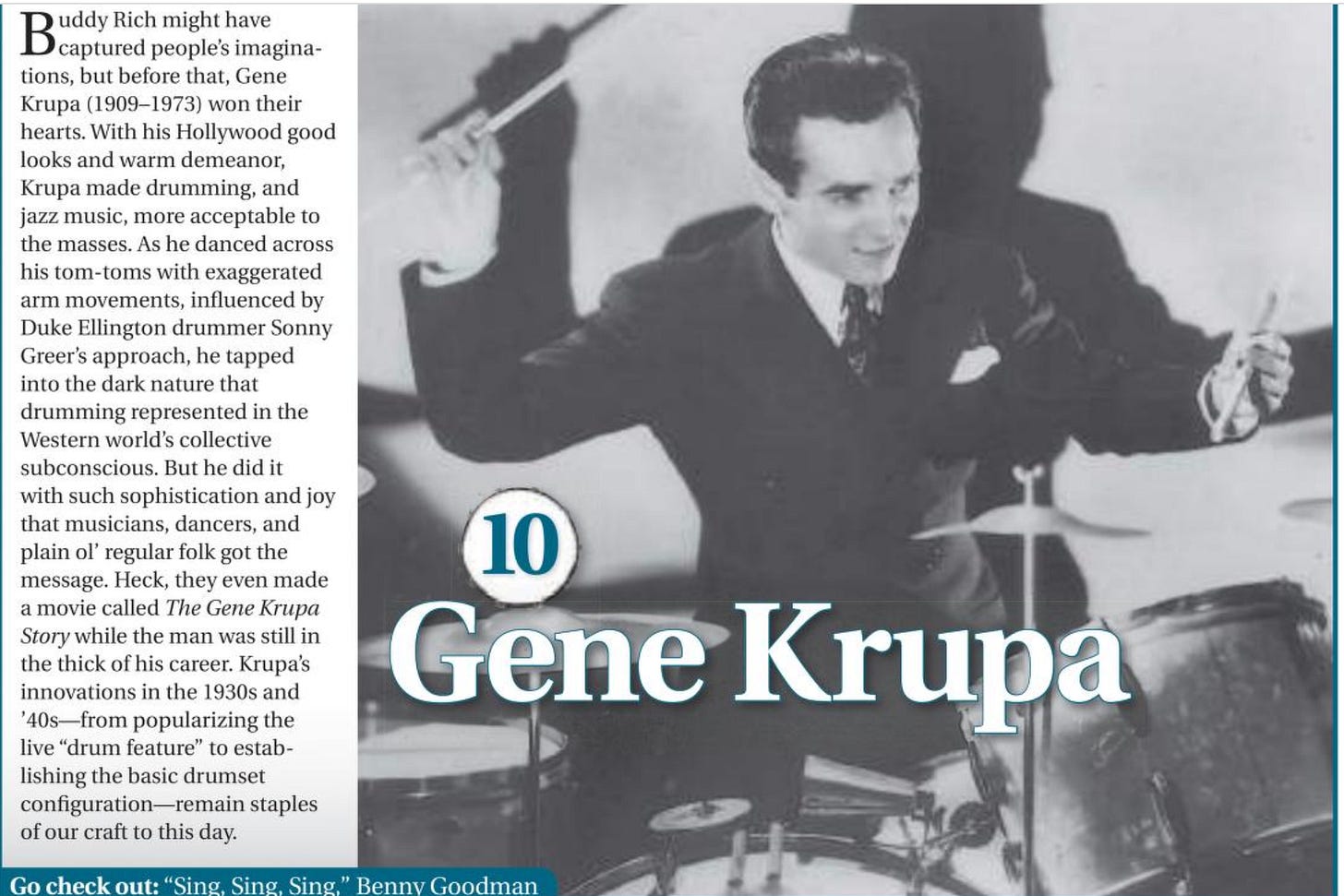

His energy and charisma propelled him into a rare level of celebrity for a jazz musician. A marquee star from the late 1930s on, he appeared not only onstage but also in Hollywood films. In 1959 he was even the subject of a biopic, The Gene Krupa Story, starring Sal Mineo. And Krupa is near the top of every list of “greatest drummers ever.” He was #7 on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the top 100. He’s #2 on the list from Music Grotto; and Number 8 at HigherHz. Modern Drummer magazine, a prime source for drummers, did a major readers’ poll in 2014 and he placed tenth:

Clearly, he was hugely influential on other drummers.

(Paying Subscribers, scroll down to download the entire 108-page issue of Modern Drummer containing the drummers’ poll, as a THANK YOU.)

But despite all this, among jazz critics and historians, and many musicians, it has become part of the “received wisdom” that Krupa was an unmusical drummer, and that he played too loud. It’s also commonly stated that Krupa was old-fashioned— but considering that he was born in 1909, that’s hardly fair. He was from an older generation, after all, and he must be judged in the context of his era. At the most, it seems that Krupa gets credit for popularizing drum features in jazz and, later, in rock music. Here I hope to make the case that he was also a creative player for his time, with a wide dynamic range.

Krupa was born in Chicago. In 1927 he was gigging in Wisconsin, then returned to his hometown and joined bassist Thelma Terry’s band (more on her below). Meanwhile, he made his first recordings, four tunes at two sessions in December 1927, with members of the circle of white musicians that jazz historians like to call “the Chicago school” or “the Austin High gang,” because most of them went to Chicago’s Austin neighborhood high school. The band included Jimmy McPartland, cornet, Frank Teschemacher, clarinet, Bud Freeman, tenor sax, Joe Sullivan, piano, Eddie Condon, banjo, Jim Lannigan, bass, and Gene. Vocalist (and comb artist) Red McKenzie set up the sessions, and even though he didn’t perform on them, the labels read “McKenzie and Condon's Chicagoans.”

Krupa and Condon regularly claimed that these recordings were the first to feature a full drum set that included a bass drum. I think they believed that, but they were wrong: full sets with bass drums are clearly audible before then, even on some of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band recordings in 1917. And in any case, the bass drum is not particularly audible on their 1927 sessions. Krupa is mostly heard at the very end of “Nobody’s Sweetheart” and “Liza,” driving the band’s lively closing ensemble with strong accents on beats 2 and 4 (a “backbeat”). He’s only audible in the very last seconds of “Sugar.”

However, on “China Boy,” you can hear his tasteful and soft drums behind the piano solo at 0:36, as well as his backbeat from 2:37 to the end. Even so, as percussion goes, it is bassist Jim Lannigan who steals the show with his constant wild “slap bass” throughout—underneath ensembles, alongside soloists, and in his own brief featured spot at 1:25:

Another fine bassist, Thelma Terry (1901-1966) isn’t usually mentioned as a member of the Austin High gang, but she should be. She was a few years older than they were, but she had attended the same school earlier. As they grew up, she was an important employer for local artists, and not only Krupa. (More on this in a later post.) When Krupa recorded with her band on March 29, 1928, she already had experience performing with a variety of groups. In fact, she may have been the first American woman instrumentalist to lead a dance band. (She was at least one of the first, for sure.) On the strength of her six recorded songs (one of which has an extra take), she was a creative musician whose playing was full of rhythmic variety and percussiveness.

The first number, “Mama’s Gone Goodbye” — a bit of a “jazz standard” that had already been recorded a number of times over the previous five years — begins and ends with Krupa’s cymbals and Terry’s bass, which makes me think that she and Gene enjoyed working together. As for her playing elsewhere on the track, listen for how she breaks up the rhythm at 0:30. Her rhythmically inventive bass playing is so prominent between 1:20 and 2:00 that this whole passage is essentially a bass solo with written sax part and band accompaniment. In fact, she and Gene are the only ones improvising on this entire recording. Let’s listen:

I’d like to note that on another recording from this session, “Starlight and Tulips,” there is what sounds like a vibraphone at 1:02. It was a new instrument at the time, so this was very likely the first time that one was used on a dance band recording. (It’s not played by Terry or Krupa, because they’re also audible. (The weird-sounding instrument after the vibes is a muted trombone.) This has never been noted before—here is the relevant excerpt:

By the late 1930s, Krupa defined drumming for many Swing Era listeners, because of the unprecedented popularity he enjoyed in groups led by Benny Goodman. His solo introduction to Goodman’s 1937 hit recording “Sing, Sing, Sing” made him a household name, and a star in his own right. Krupa became so popular that he was the only drummer that many white Swing Era fans knew by name. This led, understandably, to resentment among his peers, especially among African-Americans.

It helped a little that Krupa was by all accounts generous in giving credit to his Black idols, and that he featured Black trumpeter Roy Eldridge in his own band. Gene consistently said that his main influences included Black drummers Baby Dodds and Chick Webb. (More on Webb in a future post.) Below he sings the praises of Black musicians in general, in a guest post under Lionel Hampton’s byline, in the Baltimore Afro-American, a Black newspaper, on July 2, 1938. His language is awkward by today’s standards, but please try to read it in the spirit of 1938. Notice that in those days “boys” meant “male musicians,” black and white. (And yes, female instrumentalists and singers were called “girls,” regardless of age. All of this was true through the 1950s. In future posts I’ll address some of the biases revealed by these word choices—such as the implication that music is a “young person’s game,” not a “serious occupation,” and so on.) Of course, when he says “Boy, didn’t we have fun?,” that has another meaning, as in “Oh, boy!”

(Tommy Trent, whom he says is “going over big,” was presumably a singer, but he is unknown and never recorded. This was not the Tommy Trent who was born in 1924 who recorded country music in the 1950s.)

You can hear Black drum legend Jo Jones (a personal favorite of mine, whom I saw perform on three occasions) discuss Krupa on his 1974 album The Drums, where he talks about drummers and demonstrates on the drum kit. His one-minute take on Krupa is all about the tom-tom beat from “Sing, Sing, Sing.” (He begins by saying “Now we move up to modern times” because on the earlier tracks he had mostly discussed legendary drummers from the days before recordings.)

Now, here in fact is Krupa playing “Sing, Sing, Sing,” the piece Jones refers to, on Goodman’s famous Carnegie Hall concert, in January of 1938. The first thing you notice is the energy that Krupa brings to this band. Without Krupa, in my opinion, the Benny Goodman “Orchestra” (as it was usually billed) of that period would have been a very clean, very tight, but not very exciting organization. His playing lifts them right off the ground. Notice, too, how much variety Krupa packs into his opening riff. By no means does he keep repeating the same “simple” beat over and over as Jones suggested:

But an even better example of how Krupa lifts a band is the opening number from that Carnegie Hall concert, “Don’t Be That Way.” Goodman and his band get off to a stiff start, and the audience is quiet. But then Krupa starts dropping “bombs” (strong drum accents) and plays a two-bar break that lasts only three seconds but drives the audience wild. You can hear for yourself how they, and the other musicians, respond to Krupa’s drumming, in this audio excerpt:

Krupa did like to play his bass drum and tom-toms, especially with a big band. But he could also play with a lighter touch, as he did in the same concert on “China Boy,” the song he recorded at his 1927 debut, which he plays here with wire brushes. Listen to his unusual accenting as he drives the quartet at a very fast tempo. It’s fascinating, never just 1, 2, 3, 4. He adds unpredictable accents behind Goodman’s solo:

And when he takes a drum solo on the same piece, he's also quite inventive (that’s Hampton’s voice at the beginning):

Krupa was also very interactive — certainly by the standards of his generation. Clearly, he was listening closely to what his bandmates played. The best place to hear Krupa’s ability to interact with others is in small groups. One example of this is “Barrelhouse,” which he recorded in November of 1935 in an integrated trio with Jess Stacy, Goodman’s pianist, and Black bassist Israel Crosby, who was only 16 at the time and worked with the popular Ahmad Jamal 20 years later. The most energetic exchange occurs during the end of the track, which is excerpted here:

All three of them are going back and forth and breaking up the beat. This kind of interaction is what you might expect from drummers today, but it’s certainly not typical of the 1930s.

Beginning shortly after Goodman’s Carnegie Hall concert, from April 1938 until he died in 1973, Krupa fronted his own big and small bands. (He missed out on leading a band for most of 1943 and the first half of 1944, because he was arrested for supposedly contributing to the delinquency of a minor—his “band boy,” that is, his assistant—and having that young man "transport” marijuana, resulting in two charges. This was a complicated case which he won on appeal—I’ll cover it in a later post.)

With his own big bands, Krupa was often in the limelight in showcases that were, to be honest, not very subtle. But in small groups he was a real team player. Right into the ‘70s, he’s not dominating at all in small-group settings — he’s swinging and responsive, and he contributes to any group he plays with. Here’s “Seven Come Eleven,” from a 1963 stereo session he recorded with the reunited Benny Goodman quartet, featuring Lionel Hampton on vibes and Teddy Wilson on piano. (The tune, credited to Charlie Christian and Goodman, is most likely by the guitarist, with Goodman’s name added as the leader’s privilege. It is named for an expression used in gambling with dice, which was a favorite pastime of musicians on long bus rides). I especially enjoy the great variety of approaches that Krupa uses, how he changes the “feel” behind each soloist. Here is a lively passage during the Goodman clarinet solo:

He sort of tap dances behind Wilson’s piano solo, then swaggers behind Hampton’s vibraphone solo. Here is the complete track:

Almost a decade later, there was another Goodman reunion as part of an all-star TV jazz program. Watch the broadcast below, from October 23, 1972, and you’ll witness Krupa’s alert playing, and his wide range of dynamic levels. As trumpeter Doc Severinsen announces, this was the first televised appearance of the original Goodman quartet. But he apparently was told not to mention that it’s a quintet—George Duvivier was added on bass! (By that time, even musicians of their era preferred to work with a bass player.) Anyway, it’s clear from the start that they are all exhilarated to be playing together.

The very first number, “Avalon,” is an ideal example of Krupa’s work, illustrating his alertness, energy, variety and overall musicality. Below is the complete 12-minute segment. (I have it cued up—if it doesn’t start with Doc’s announcement, please move it to 30:07.) If you only have time to hear two minutes, please check out Gene’s exciting and supportive playing from 33:42 to the end of that first number.

By the way, when Benny holds up a finger at 32:03, it means “I’ll take another chorus”—when he points toward Teddy at 33:05, it means “Please take another chorus.” The second number is “Moonglow,” and they wind up with “I’m a Ding Dong Daddy from Dumas” (that refers to Dumas, Texas).

Oh—and before you watch, let’s acknowledge that Hampton was always learning new things. He plays a diminished pattern at 38:05, uses four mallets at 38:56, and throws in a bebop substitution at 40:50. More on Hamp another time—now, ENJOY!:

Krupa was also quite open to the newer sounds. He hired such younger modernists as Red Rodney, Urbie Green, Frank Rosolino, and Frank Rehak, and his writers and arrangers included Gerry Mulligan, Budd Johnson and Eddie Finckel. He employed singers Buddy Stewart and Dave Lambert, and recorded their early bop vocal performance of Lambert’s “What’s This?” in January 1945 (the year given at this link is wrong):

So as far as I’m concerned, Gene Krupa was a marvelous musician who gets a bad rap just because he was more popular than some critics and musicians thought he deserved to be. And as far as being loud, haven’t you heard Art Blakey, Max Roach and Elvin Jones? Some of the best drummers in jazz play loud! But Gene himself said in DownBeat, on March 29, 1962: “My job remains…to keep time, to extract appropriate, supporting sounds from the instrument, to be a musician.”

Let’s end by going back to Jo Jones, who presented Krupa with an award at an all-star event in Central Park on July 7, 1973 during the “Newport Jazz Festival/New York.” Krupa speaks briefly as well:

Gene died three months later, at his home in Yonkers, New York, at the age of 64, from heart failure, apparently brought on by years of leukemia and emphysema.

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. P.S. I posted a much shorter and very different version of this at WBGO.org in 2018 and that one was edited by Nate Chinen—thank you, Nate!

Also, If you’d like to learn about Krupa as a person, read this touching and detailed personal reminiscence by pianist, singer and songwriter (“A Taste of Honey”) Bobby Scott. By the way, I met with Scott around 1983 to discuss Lester Young. He was a gifted storyteller and he left with me bound copies of unpublished short fiction stories that he’d written—as well as cassettes of some very pretty classical chamber music that he had composed.

P.P.S. Paying subscribers, your gift is below!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.