George Shearing, 1: His Early Bebop Compositions (+Bonus)

(Paying Subscribers, a Shearing piano book is Attached for you, with Thanks.)

George Shearing (1919-2011) became identified, even in the headlines of some of his obituaries, as the composer of “Lullaby of Birdland.” And that’s the title of his autobiography. Like many a trademark hit, this song could be a mixed blessing. In his book, Shearing struck a perfect chord of ambivalence: “I've played it so many times that it is possible to get quite tired of doing so — although I never tire of being able to pay the rent from it!”

There was much more to this pianist and composer, but to learn about that one has to go back to some of his early recordings — like “Conception,” which Shearing first recorded in July 1949. Here is a film of the tune from late 1950, with Don Elliott (vb), Chuck Wayne (g), John Levy (b), and Denzil Best (d). This was a “telescription” made for TV (by the Snader company), so, fortunately, the sound is “live,” not dubbed in. Shearing displays his famous facility with fast-moving chords starting at 1:58:

Shearing had a unique approach to composition, and this tune was recorded by many well-known musicians. Beboppers loved improvising through the form of “Conception,” as it’s a challenging piece that moves quickly through a number of keys. Its A sections are 12 bars apiece, rather than the more common eight, and it begins as if it’s in the middle of something, with a lot of forward momentum. All this has led to some controversy over the authorship of the tune — a point that illuminates some of the biases around Shearing’s work. More on this to come.

First, a little biographical background: Blind from his birth to a poor family in London in 1919, he showed talent on the piano from around age three. He was then classically trained, and developed a strong interest in jazz after hearing recordings by Art Tatum and Fats Waller. From age 12 to 16 he lived and studied at the Linden Lodge School for the Blind, where, among other things, he learned Braille music notation. (He later used that to write his compositions, and then had various people over the years to translate that into standard printed notation.) At 16, Shearing left school to play in a London pub. By 18 he was recording in a kind of Tatum-meets-Teddy Wilson style, and quickly gained fame in the UK, even leading his own BBC radio show.

One early and important advocate was Leonard Feather (1914-1994). Feather, also British-born, was a composer and a capable pianist, but is best known today for his jazz journalism. Among many other accomplishments, he invented the “blindfold test.” Just for fun, let’s listen to “Squeezin’ the Blues,” an improvisation by Feather on piano, and Shearing “squeezing” an accordion, from London in March 1939:

Feather moved to New York City in September 1939, and was later one of the first writers to pay serious attention to the bebop movement. His 1949 book, Inside Be-Bop (later re-titled Inside Jazz), was the first to survey the new music. (That same year, Billy Taylor published a “How To” book for pianists seeking to play bop.) Inside Be-Bop was innovative in that it included musical analysis with notation, along with brief bios of many notable bop musicians (a preview of Feather’s later Encyclopedia of Jazz).

With Feather’s encouragement, Shearing moved to New York in 1947. Although he had begun recording in the late Swing Era, he was the same generation as Bird and Diz, and he soon found himself immersed in bebop. At the beginning of 1949, again thanks to Feather’s suggestions, he formed his unique quintet that featured a blend of vibraphone, guitar, and piano over subdued bass and drums. He had been composing bop pieces in his own distinctive style, and this group was the ideal medium for performing them. Shearing mentions some of his early compositions in his book. He was a witty guy, and many of his titles are puns:

I actually started composing during the war. …“Delayed Action” was actually one of the first that I wrote and went on to record. And then came a string of others, including “Bop's Your Uncle.” I wrote a number of pieces dedicated to the members of my family, at least a couple named after Wendy [his daughter], and one for Trixie [his first wife] called “How's Trix.”

“Delayed Action,” from 1941, goes through several stages, from a moody opening to stride and even a bit of boogie-woogie, before returning to the hesitant, “delayed” beginning. Shearing wrote that it was named after the delayed time bombs that fell during the Blitz. He explained, “it had a kind of suspension in the left hand that I held onto for a very long time, until suddenly it resolved, and the tempo picked up again, and that was the ‘delayed action’ of the title.”

Eight years later in 1949, “Bop’s Your Uncle” (this title was a pun on the British expression, “Bob’s Your Uncle”) shows that he has changed, and has fully absorbed the modern composition style. That one is fairly routine, but many of his bop themes show a refreshing originality. Let’s hear a few of them:

One of my personal favorites is “How’s Trix” (a joke on the expression “How’s tricks?,” as well as a dedication to his wife) from April 1950. It’s a memorable AABA piece, and the bridge, starting at 0:19, is especially lyrical, a bit like the main theme (A section) of Gillespie’s “Woody ‘N’ You.” This features the same group as “Conception” above, except that his original vibraphonist, Marjorie Hyams, is here:

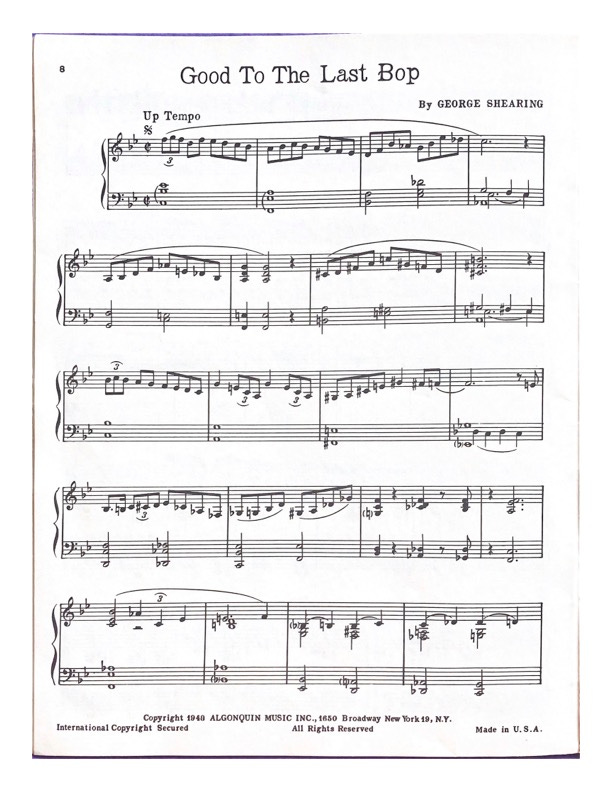

On some of these pieces, he still played accordion. “Good To The Last Bop,” from February of 1949, is one of those. (The title is another pun—Maxwell House Coffee has been advertised as being “Good to the last drop” since around 1915.) This is another one with an unconventional form: It’s ABA, with a A that is 16 bars, followed by an eight-bar bridge, followed by another 16 bars. Here is the original sheet music from 1949. Measures 9-12 of each 16-bar section feature chords descending by thirds (see the third staff on the first page)— a rare compositional device at the time!

And here is the recording, from February 1949. George plays the theme on accordion, and Hyams provides piano chords behind the theme and his solo. At 1:05 she stands up and he sits down to play piano chords behind the guitar solo, then takes a piano solo. On the closing theme, unlike the beginning, Hyams plays vibes and Shearing plays piano.

Another side of Shearing was his classically-influenced solo piano work. As early as June 1949, he recorded his beautiful and introspective arrangement of “Summertime.” It’s virtuosic, Tatum-esque, even reminiscent of British composer Cyril Scott, who, I showed, Tatum likely heard. It even anticipates what Bill Evans would sound like nine years later—and Evans was definitely listening to Shearing. (I know this from having studied Evans’s home recordings made in the late 1940s.) Overall, it’s totally Shearing’s own approach. Let’s listen:

A few years later, in 1954, he published the first volume of his “Interpretations for Piano,” a series of eventually seven books that featured solo piano reharmonizations of popular songs. Such books were often “ghost-written” by staff musicians, but these appear to be authentic Shearing, because the arrangements are way more sophisticated than what one usually finds in these types of books. The influence of Tatum on Shearing is noticeable throughout. However, the books use primarily quarter and eighth notes—no super-fast runs—in order to keep them playable for amateur musicians. And the series sold well and became widely used.

(Paying Subscribers, the first volume of his “Interpretations” is attached for you below!)

But at gigs, Shearing always appeared with his quintet, not solo. Author Jack Kerouac chose the Shearing group of 1949 to exemplify the intensity of the jazz experience, in his iconic novel On the Road. In a scene depicting Shearing on the bandstand, Kerouac notes how “he began rocking fast, his left foot jumped up with every beat, his neck began to rock crookedly, he brought his face down to the keys, he pushed his hair back, his combed hair dissolved, he began to sweat.” The passage continues:

Shearing began to play his chords; they rolled out of the piano in great rich showers, you’d think the man wouldn’t have time to line them up. They rolled and rolled like the sea. Folks yelled for him to "Go!" Dean was sweating; the sweat poured down his collar. "There he is! That’s him! Old God! Old God Shearing! Yes! Yes! Yes!" And Shearing was conscious of the madman behind him, he could hear every one of Dean’s gasps and imprecations, he could sense it though he couldn’t see. "That’s right!" Dean said. "Yes!" Shearing smiled; he rocked. Shearing rose from the piano, dripping with sweat; these were his great 1949 days before he became cool and commercial. When he was gone Dean pointed to the empty piano seat. "God’s empty chair," he said.

The reference to “his chords” refers to Shearing’s legendary prowess at playing fast passages made up of chords rather than single notes. This is usually called “block chords” or “locked hands” style, because the hands have to move closely in sync. He had a routine of building his solos from single-note lines to chord passages, so that the chords tended to happen at about 1:50 in each 3-minute recording. For examples, go back to about 1:50 in “How’s Trix” and “Good to the Last Bop.” And, as I noted, you can clearly see him play this way at 1:58 in the film clip of “Conception,” above.

Fats Waller reputedly once declared Tatum to be “God,” and it’s obviously high praise indeed for Kerouac’s friend Dean to apply that epithet to Shearing. But the contrasting negative reference to Shearing’s “cool and commercial” period is striking, given that Kerouac wrote On the Road in 1951 — only a couple of years after those “great 1949 days,” and a year before the publication of the song “Lullaby of Birdland.” This indicates how quickly the perception of Shearing shifted. We can see reverberations of this shift in the debate around “Conception.”

We’ll dig into the debate on Shearing in Part 2, soon.

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. On the Road was not published until 1957, after a number of edits. More recently, the original 1951 “scroll”—it was written on a long scroll of paper—was published. The only difference in the passage above is that the year 1949 was not in the original—it just said “his great days.” Apparently by 1957 he, or his editor, felt that so much time had passed that the year would have to be specified.

P.P.S. A shorter version of this essay was published at WBGO.org in 2018. This updated and expanded version still benefits from the fine editing of Nate Chinen on the original post.

P.P.P.S. Paying Subscribers, keep scrolling down please.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.