Last time, we reviewed some of Shearing’s history, listened to his adventurous early bop compositions, and introduced his piece “Conception.” When I read Peter Pullman’s well researched biography of Bud Powell, one of my own piano gods, I noticed a footnote (p.427 in the printed book) where Peter reports that some musicians who knew both Powell and Shearing believed that Shearing was not capable of writing “Conception.” Instead, they suggested that Powell was a more likely author for the tune. The musicians who suggested this included Al McKibbon, who was Shearing’s main bassist in the 1950s, and pianist Claude Williamson. Elsewhere, clarinetist Buddy DeFranco and composer/saxophonist Gil Melle expressed doubts about Shearing’s authorship. This opinion has gotten out into the mainstream, and I’ve known musicians and fans to refer to it as Bud’s tune. The only reason ever given is that the tune is supposedly “too advanced and difficult” for Shearing to have written it.

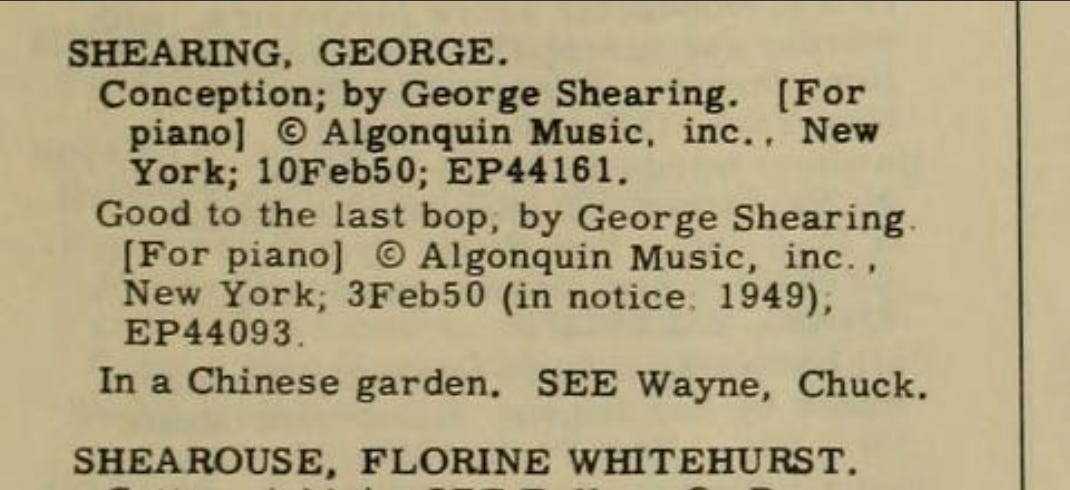

They are all 100% wrong. I’ve already provided, in the previous essay, several examples of advanced bop compositions for which nobody has ever challenged Shearing’s authorship. So why would anyone doubt that he could have composed one more in a similar vein? Besides, Shearing recorded “Conception” in 1949, and in 1950 he published the piano sheet music and copyrighted it, as you can see here:

And last time you saw the film of Shearing performing it in 1950. One might perhaps choose to overlook one of these details, but would it be foolish to ignore all of them.

And there’s more: Powell only started to perform “Conception” after others took it up. His earliest surviving version of “Conception” is a radio broadcast in 1953. He recorded his only studio version of it in 1955. He continued to perform it at gigs into the early 1960s (he died in 1966), but he never claimed it was his. More important, this tune, with its tricky theme and modulations, is not what he was about as a composer. There is no Bud Powell piece that sounds anything like “Conception,” whereas it is clearly in Shearing’s style, as I showed last time.

So why question Shearing’s authorship, and argue that Powell wrote the piece, when it fits clearly within Shearing’s recorded and published output — and when Bud wasn’t associated with the tune, didn’t record it until years after Shearing, and never claimed it was his? There is absolutely no reason to question that Shearing wrote “Conception.” Why create a problem where there is none?

But this does fit within a pattern. I think it’s a case of what can happen when an artist gets stereotyped by a big “hit.” Erroll Garner, a terrific pianist who at his best was a quite uninhibited improviser (I recommend his solo works, such as Solo Time), was similarly typecast as the author of “Misty.” In jazz there’s a strange kind of elitism—everyone of course wants to be successful, but if someone becomes too successful, jazz musicians and fans assume he or she has “sold out,” gone commercial.

What happened here, partly, is that Shearing’s early accomplishments in bebop were eclipsed by his later successes. His light-hearted, medium-tempo version of the songbook ballad “September in the Rain,” recorded at the same 1949 session as “Good to the Last Bop,” which we heard last time, is a case in point. The first thing most people know about it is that it sold nearly a million copies. But like all “hits,” this wasn’t planned, and could not have been. In fact Shearing plays some particularly wild piano on it. You can easily find the whole recording online, so I’m going to give you just the last 80 seconds, to focus on his uncompromising solo, which is followed by a slightly “out” ending. Clearly, Shearing was not thinking “How can I make a big pop hit?” It makes no sense to “blame” him for the success of the recording. Let’s listen:

Then of course there’s the best-known of Shearing’s own compositions, “Lullaby of Birdland,” from 1952. It may celebrate Charlie Parker and the famous nightclub where bebop was played, but it’s really a bouncy swinger, not one of Shearing’s complex bebop tunes. It’s more in the vein of “Bop, Look, and Listen,” which he recorded in February 1949, again at the same eventful session as “September in the Rain.”

More than a hit song, “Lullaby of Birdland” became a standard, especially after it was outfitted with lyrics by George David Weiss (credited as “B.Y. Forster,” for copyright reasons). If you listen to jazz singers at all, you have probably heard a version of this song, by Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Mel Tormé or dozens of others.

The impact of these two recordings was such that Shearing became a “star.” But at first it did not appear that he was about to pursue a pop career. From 1953 on, Shearing became very active in the Latin jazz movement. His Latin group featured vibraphonist Cal Tjader briefly, and other noted Latin artists such as Armando Peraza on congas. And he maintained a high level of artistry in his band into the next decade; vibraphonist Gary Burton was a member of his quintet from 1963 to ’64, composing all of the fascinating material on the album Out of the Woods.

But at the same time, starting in 1955 when he switched to the Capitol record label, his Latin and jazz albums were interspersed with some featuring string orchestras, and others featuring the label’s star singers such as Nat Cole and Nancy Wilson. And from the late ‘60s into the early 2000s— a long stretch of time — Shearing became identified with a kind of “jazz lite.” It was indeed very popular, but not respected by hard-core jazz musicians and fans. And he frequently performed in hotels, which is a different sort of career and audience from playing in jazz clubs. So in a sense, he, and his management, took himself out of the mainstream of jazz performers. And he made his situation among serious jazz people worse by avoiding his more innovative material. Not entirely – you’ll find that once in a while in his later recordings, he’ll play one of his complex bop pieces in the middle of a set. But he wasn’t primarily associated with this strain of material, or with serious jazz gigs, after the late ‘60s.

The long and short of it is that many jazz musicians developed the impression that he was some kind of cocktail pianist. They either forgot or never knew that he started as a quite serious jazz player. Ironically, it has been my experience that “classical snobs” who don’t like jazz do tend to like this side of Shearing, because it’s pleasant and, they add, “he’s not trying too hard to make serious music.” (Don’t get me started on that one.) But if you review the audio examples in the previous essay on him, you will find some quite impressive music.

Meanwhile, to get back to his best-known jazz composition, "Conception," it became closely associated with Miles Davis. First, Davis created his own version of the tune in 1950 for what later became known as his Birth of the Cool sessions, calling it "Deception." Jeff Sultanof, editor of the published Birth of the Cool scorebook, was able to study the original handwritten music. He noted that the intro, first chorus and coda of “Deception” are in an unknown handwriting. (I too compared it with Miles’s writing to be sure it is not his.) The middle—primarily backgrounds for the solos—is definitely in Gerry Mulligan’s hand. (It’s important to point out that Mulligan was a fine composer, and did more writing for these sessions than anyone else — more than Gil Evans, who is usually mentioned first.) Sultanof concluded that Miles himself composed “Deception,” that it was written down by an unknown friend of his; and that the middle was then filled out by Mulligan, following the structure already set forth in the first chorus. Sultanof explained the whole process in this detailed article. The score and parts of “Deception” and the other Birth of the Cool pieces are available from Jazz Lines Publications.

Returning to the recording, Miles’s version adds several twists, or “deceptions.” First of all, he changes the key to c from Shearing’s key of D-flat. Then, most important, he uses his own theme, not Shearing’s, but it is written to fit Shearing’s chord sequence. Judging from Shearing’s autobiography, he didn’t quite “get” what Miles was up to: “Miles Davis once made a very famous recording of my tune ‘Conception.’ He was a master of playing the wrong bridge, or making up his own, which is what he did on that piece.”

Miles did change the bridges of pieces on occasion. But in this case, Shearing missed the point. Miles’s piece is a complete rewrite. He doesn’t just make up a bridge, and certainly doesn’t play the wrong one. In addition to a totally new melody throughout, his tune has two extra bars in each A section which expands the “pedal point” section. (As I will show in a later essay, pedal points became an important part of Miles’s composing and arranging.) And finally, Miles starts with an eight-bar introduction, which is really the last eight bars of the theme — but since one doesn't know that on first listen, it’s impossible to follow the form at first hearing—one has to listen a few times. before it makes sense. The theme really begins at the nine-second mark:

There’s more to the “Deception”: At 0:52, coming out of the bridge into the last A section, the first 4 bars are different from the previous A sections. Miles uses a long line here that flows right out of the bridge, once again making it difficult, “deceptive,” to hear where the next section begins. And Miles’s solo that follows is ABA, with no repeat of the A section. And—yet more—the last A section that starts at 1:35 is now 15 measures long! (The fifth measure is the added bar.)

Still, Miles did not hide that his “Deception,” although it’s a totally new piece, was inspired initially by “Conception.” For an illustration, hear the first surviving recording of Miles playing it, on a radio broadcast with Stan Getz, J.J. Johnson, Tadd Dameron, Gene Ramey, and Art Blakey, in February of 1950, a month before the studio version was recorded:

On this version, they play Shearing’s theme for the first two A sections, then they switch (at 0:23) to Miles’s “Deception” for the bridge and the last A! (They play it in Db so that they don’t have to modulate to C.) And it’s Miles’s form, with the extra measures, that they use for the solos. Miles used this same arrangement again when he recorded “Conception” in the studio for Prestige in 1951.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this exploration of the world of George Shearing—a much richer and more varied world than most people remember.

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. A shorter version of this essay was published in at WBGO.org in 2018. This updated and expanded version still benefits from the fine editing that Nate Chinen did on the original post.

P.P.S. Paying Subscribers, keep scrolling down please for your gift.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.