(Dear Paying Subscribers, at the bottom you’ll find a short film clip of Page on trumpet that has never before been available, plus rare audio.)

Oran Alfred Page (1908-1954) earned his nickname “Hot Lips”by playing trumpet in an exciting and expressive manner. (Alfred was his middle name, but he sometimes gave it as Thaddeus.) He was also a fine singer. Page’s story has been told most thoroughly in the biography by Todd Bryant Weeks. (The book grew out of the Master’s thesis that Todd completed under my supervision.) Today, we’re going to focus in on a part of his story, related to letters that Page wrote to songwriter Harry Weinstein (1910-2005). We thank Weinstein’s grandson, Lee Rice Epstein, for sharing these with us. Epstein provides some background about his grandfather:

Harry Weinstein ran a cutting machine repair and supply shop on West 35th Street in Manhattan. But in his free time he was, says Lee, “an aspiring and enthusiastic songwriter,” a lyricist. He has about ten songs registered with B.M.I. that were not commercially recorded. There were another ten that were recorded and sold in stores. ”He was able to get singles cut in the ‘50s and ‘60s by studio musicians,” Lee explains. Weinstein’s most successful song was co-written with saxophonist Eddie Barefield, “whom he spoke about often and lovingly,” says Lee. That song, "Two Wrongs Won't Make It Right" (sometimes listed, incorrectly, as “Two Wrongs Don’t…”) was recorded by singer Joe Carroll, credited to Barefield and Weinstein, in that order. Here’s the 1952 recording:

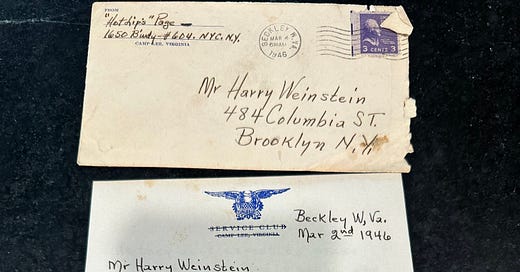

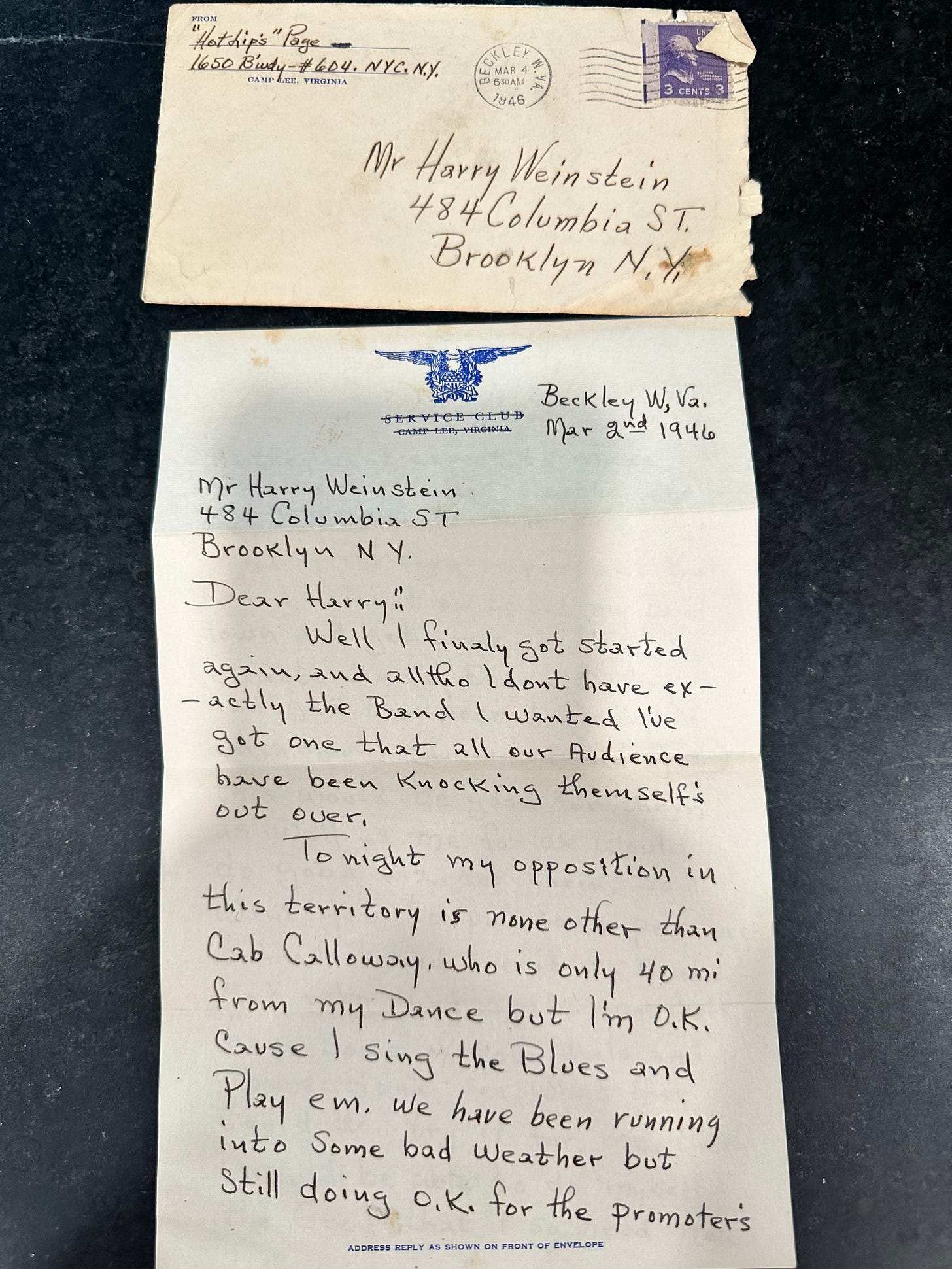

Barefield and Page knew each other from Kansas City and had recorded together as members of Bennie Moten’s band in 1932. Weinstein probably met them, says Lee, the same way he met many musicians: “Harry was a regular at all the nightclubs and always willing to help anybody who needed a hand.” In the first letter we have from Page, written March 2, 1946, he’s just checking in, letting Harry know what he’s up to. Notice that Page’s return address is 1650 Broadway in Manhattan. This was not a residence—this building, along with the Brill Building about a block away, held the offices of many music publishers, songwriters, and booking agencies, and even housed recording studios. These two buildings were centers of the American popular music business from the 1940s through at least the 1960s. Musicians like Page often used such an address as a reliable place to receive mail when they were away on tour.

In the letter, he talks business with Harry. He says he didn’t get exactly the musicians he wanted, but that audiences love the band he has, and he hopes to make some money with it. He’s writing from Beckley, West Virginia—a regular tour stop for Black bands in those days—and he’s not worried about Cab Calloway performing in the area, because “Lips” sings and plays the blues, which, he implies, is in demand. At the bottom, Page provides the phone number for “Evan,” “just in case,” which apparently means that Harry should phone that person if he gets any leads for gigs or promotional ideas. Here’s the letter:

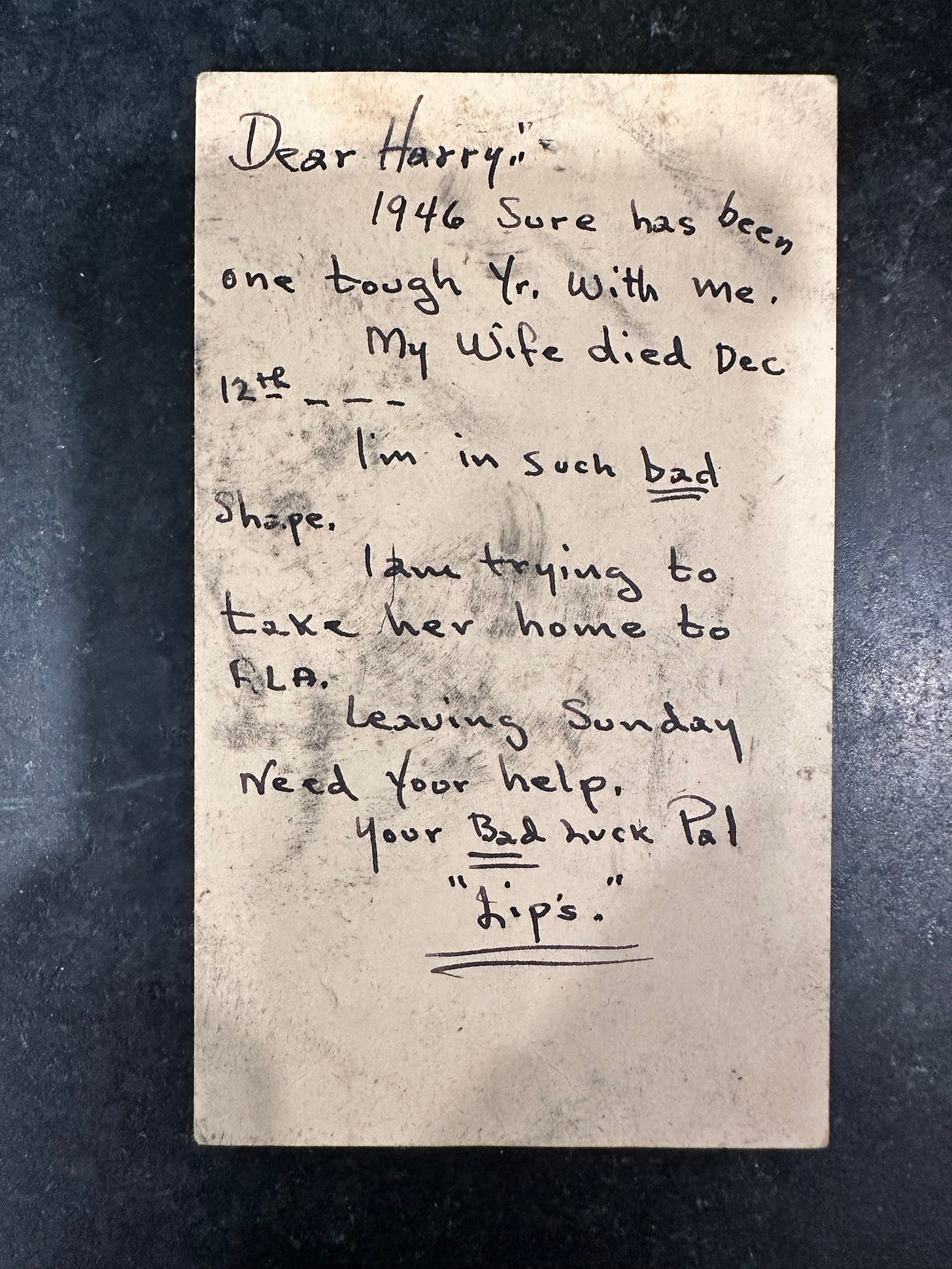

That letter is positive and upbeat. But the second letter, postmarked December 14, 1946, is a desperate cry for help. This time Page gives his home address, an apartment building on Edgecombe avenue, near 140th Street in Harlem. His wife had died in childbirth and he says “I’m in such bad shape…need your help.”

Very sad! Todd Bryant Weeks provides some details in his book:

[Page’s wife] Myrtle had been admitted to Harlem Hospital on Tuesday, December 10…Thirty-nine hours later, on December 12, 1946, Myrtle Sterrs Page was dead of complications from childbirth. The infant did not survive.

…Down Beat gave brief notice to this event in its January 1947 issue, saying only that, “Myrtle Page, wife of Lips, died in New York City. Lips accompanied his wife’s body back to Montgomery, Alabama, for burial.” She was buried eight days before Christmas, on December 17. [Their 7-year old son Oran, Jr., known as “Spike”} was deposited in Montgomery with his grandmother Eloise and his aunt.

Myrtle’s death was a devastating blow. She was all of twenty-eight, and the couple had been together for thirteen years, since she was little more than a girl. Lips had been responsible for her move to New York and had shepherded her through her late teenage years, acting as both a father figure and husband to her. As a freelance musician who traveled frequently, the thought of being a single parent must have been daunting. And with Spike now in Montgomery, he was suddenly very much alone.

As you may know, Page had many positive experiences over the next years, and some successes, but he constantly struggled for recognition. He died at the age of 46 on November 5, 1954. Let’s close with some happier memories of this sensational artist. “The Sheik of Araby” was one of his specialties. There are five or six surviving recordings of Page performing this song. The first version is from a program led by guitarist Eddie Condon that was broadcast on radio from Manhattan’s Town Hall on May 27, 1944. This was one of a weekly series of shows with varying “all star” personnel, and here Page is supported by Gene Schroeder (p), Condon (g), John Kirby (b), and Sonny Greer (d). Page’s own arrangement always began with him playing a duet with the drummer:

(For Paying Subscribers, an even more spectacular version is below.) If you wish to have a guide to all of Page’s recordings, you can download the PDF by my late friend Jan Evensmo, here. There are complete guides to about a hundred other jazz artists on that site as well.

Now, before we finish for today, film historian Mark Cantor has discovered an unknown TV appearance of Page from 1954. Access to this is restricted, but filmmakers who wish to license clips to this and other items in Mark’s huge collection may contact him at markcantor@aol.com . In the meantime, Mark has graciously agreed to share two teasers: Paying Subscribers will find below an excerpt of the film where Page plays two exciting blues choruses on trumpet! And for everybody, here are two stills from the film, showing his unidentified band members. If you recognize any of these musicians, please let me know:

And to close today’s essay, here is a photo that Page signed to his friend Harry Weinstein:

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Thank you to Lee Rice Epstein, Todd Bryant Weeks, and Mark Cantor for help with this essay. Paying Subscribers, keep scrolling down to see a short film clip of Page on trumpet that has never before been available, plus rare audio.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.