There are several excellent biographies of Charlie Parker (1920-1955). For example, archivist and jazz historian Chuck Haddix presents all the known facts of his life, including substantial original research. Pianist and historian Brian Priestley of the UK covers the life story as well, with insightful discussion of the music. (This supplants his short 1984 volume. Please note, his name is not spelled Priestly.) And saxophonist and historian Carl Woideck carefully details what is known of his life and of the music, with notated examples. (I omit the novelistic first part of the biography by the late Stanley Crouch because he only wrote about Parker’s life up to 1942, leaving the story very unfinished.)

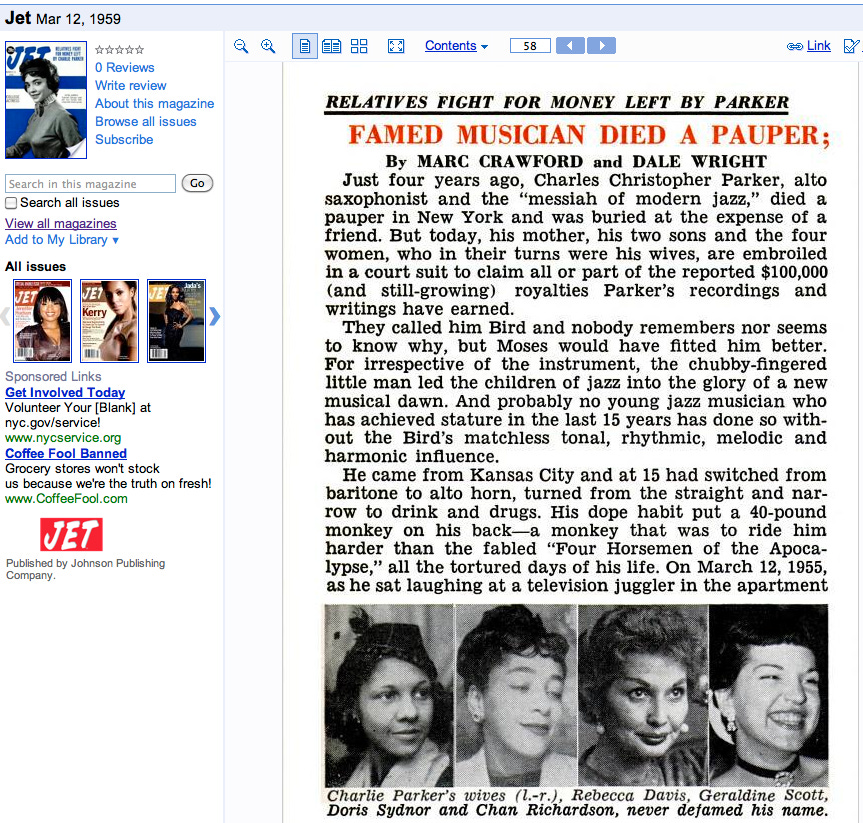

But what happened to his estate after Parker died? The black magazine Jet had an interesting story about that in 1959, with photos of family members. Jet was founded in 1951, as a weekly source of general, music and entertainment news of interest to Black readers. The last print issue was in 2014, and for a while it became a digital publication. Today it still has a website but I don’t see any new content being generated.

The articles were written in a kind of informal, chatty style, but I trust this one because it has the byline (author credit) of two distinguished Black journalists:

Marc Crawford (1929-1996) was a respected and award-winning writer on jazz and other subjects for Life, Ebony (where he was also an editor), and other publications. He also taught at N.Y.U.

Dale Wright (1923-2009) was the first Black newsperson at the New York World-Telegram and Sun (which published its final issue in 1966; a successor lasted only into 1967). There he earned a national prize and a Pulitzer Prize nomination for his reporting on the plight of migrant workers. He later served as an editor at both Jet and Ebony.

A few notes before you read the article: Parker’s first instrument was indeed a baritone, but it was a baritone horn, kind of like a small tuba (not a baritone sax). His first wife Rebecca’s reference to the “tenor sound” at the end is probably not an error—I think she means that Bird had a “tenorish” sound on the alto (you might or might not agree). Patricia, “who died in infancy,” must be the daughter known as “Pree.” And Bird was not 35 when he died—he was about 34 and a half.

There is a strange caption under one of the photos which is not explained in the text: It says that Bird’s mother “believes her son was murdered.” Obviously, that is false; there are a number of witnesses to how he died. I do have a little info about his death which I will share at a later date.

OK, here is the article:

After the Parker article, there are three interesting news items on the last page—for one, the BBC refused to play Nat Cole’s recording of “Madrid,” based on “Habanera” from the opera Carmen, because it was “jazzed up.” That is, some head person at BBC was offended that Cole’s version was “disrespectful” to the original opera. (But the word “banned’ is misleading. The British radio and TV decided not to broadcast it, but there was no government involvement, and fans could buy the record in shops with no problem. In fact you can see the British 45 rpm single here.) As to why the BBC didn’t object to Carmen Jones in 1954, there could be any number of reasons—it could be as random as that the jerk who made the 1959 decision was not in charge in 1954.

I hope you found this exploration of Parker’s world as of 1959 interesting!

All the best,

Lewis

I’d dare say that his blackness and poverty killed him. I don’t have enough words of praise and respect for geniuses like Charlie Parker who in spite all they had to endure gave the world the gift of their supreme art. Thank you very much for this wonderful post.

The booze likely killed him not the dope