(Paying subscribers, an exclusive transcription plus an alternate take recording are at the bottom for you!)

I posted a previously unknown private home recording of James P. Johnson some time ago. At that time I promised you that I would post the other recordings from that same day, which have been issued, but only on a hard-to-find LP. Before I do that, I really want to give you a sense of what was so amazing about James P., and why he was so admired among musicians in his lifetime.

There are some resources for you to know about: Johnson was interviewed two years before he died by one Tom Davin, who published transcripts in the short-lived but very notable magazine Jazz Review. (After Davin died, I learned from the late Martin Williams that any tapes and additional transcripts were, unfortunately, not saved by his family.) Dr. Scott Brown has been researching Johnson since he was an undergraduate in college. He published the only book about Johnson in 1992, and his extensively revised and expanded second edition is due to be published in 2024. I’ll keep you posted on that. In the meantime, pianist Ethan Iverson has posted online the best overview of Johnson’s music, including transcriptions. (Ethan is of course the author of his own Substack series as well.)

As Iverson notes, when a group of pianists would get together to play for each other, the consensus is that James P. was the one they all looked up to. As his turn came to play on a given song, they would watch in delight and amazement as he came up with a different approach to each chorus. He could go on at length with endlessly inventive variations.

I wish I could say that there is a recording that captures Johnson playing for 10 minutes or more like that. There isn’t. But I don’t doubt that he could go on and on, because the recording you’ll hear today feels almost like an excerpt of an ongoing longer performance. He had to end it, because in the days of 78 rpm recordings, the maximum length of each side was a little over three minutes. Still, it gives us a clear sense of how he went about creating his variations.

What is Johnson’s method on this recording? First of all, he truly does create “variations,” almost in the classical sense, where each variation has its own character. Think of Mozart’s famous variations on what we call “Twinkle Twinkle, Little Star.” (He knew it as “Ah! Vous Dirais-je, Maman.”) Each variation has an approach that runs through it—one features 16th notes in the right hand, one has 16ths in the left, another has triplets in the right, then there are triplets in the left, etc.

In classical music, each variation has its own tempo, and when the theme is in the major mode, there is usually one variation in minor. Neither of those things happens in jazz. But otherwise, Johnson’s process is more similar than one might think to the classical approach. That is somewhat surprising because, contrary to what one might expect if one is new to jazz, this is not the way most jazz musicians improvise. For the most part, jazz musicians improvise a line on top of the chords, and continue building that line through successive choruses. (Each time through the chord sequence is a chorus. Check out, for example, the amazing unreleased Lester Young solo that I posted some time ago. He improvises for three choruses.) It is simply not true, for example, that the variations that Bach created on the harmonic progression of the aria in the Goldberg Variations (one of my all-time favorite pieces of music) resembles what jazz musicians do. We do not attempt to make each chorus independent, nor to create each one in a different style from the one before. Most especially, we do not change tempos for each chorus! If anything, drive, and continuity between choruses, are more important to us.

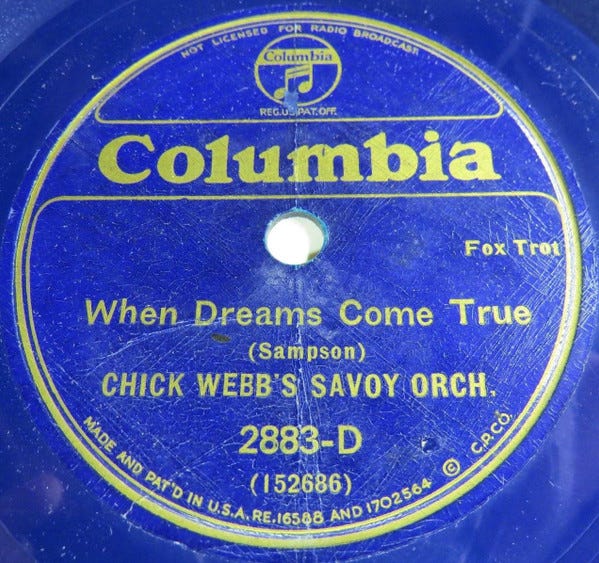

Johnson’s version of “If Dreams Come True” was recorded on June 14, 1939. The melody and words were written by Black saxophonist-composer Edgar Sampson and copyrighted by him in December 1933. In January 1934, Chick Webb made its first recording, and for unknown reasons—perhaps an outright error—the label said “When Dreams Come True”:

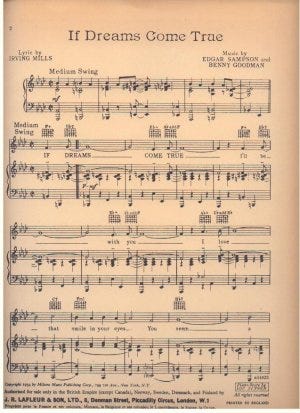

The original 78 label, as you can see above, and the sheet music, listed Sampson alone. But Benny Goodman’s band recorded it in 1937, and in 1938 the copyright was revised, and the sheet music now credited the melody to Sampson and Goodman, and the lyrics to Irving Mills, as you’ll see below. That's because it was common for leaders like Goodman to require a co-credit so that they would earn royalties as “payment” for their agreement to record a song. (Goodman’s name is also on Sampson’s biggest hits, “Stompin’ at the Savoy”—along with Webb’s name—and “Don’t Be That Way.") Manager-promoter Mills had a similar agreement with clients of his, such as Duke Ellington.

(I recommend that you read for free the most detailed article on Sampson, from Vintage Jazz Mart, a periodical that presents new research on early jazz.)

The first recordings of the song were instrumentals, but Ella Fitzgerald made a vocal recording with Webb’s band in December 1937. A month later, in January 1938, Billie Holiday and Lester Young were featured on another vocal version led by pianist Teddy Wilson, who kept it in his repertoire for many years. The song never became a “standard” among modern jazz players, and since the 1950s it has mostly been played by musicians who specialize in older jazz styles, such as stride piano.

The structure of the song divides into two halves. It’s a 32-bar form that we describe as ABAC, with each of the four sections being 8 measures long. If you want to get to know the song before hearing Johnson’s recording, Billie’s version is here. And below is the first page of the revised sheet music, with the added “co-composers”: “If dreams come true, I’ll be with you,” and so on. That’s what Billie sings. (Ella starts with a different lyric—I suppose that’s a second verse?) Here it is:

(I only have this page, from the British edition. If anyone has more pages, or higher resolution, please share it with me. THANK YOU.)

Here is an outline of what you’ll hear as James P. performs this song:

First chorus: Introducing the theme. He adds embellishments, and fills in the pauses between phrases. The chorus ends with a kind of “motto” which will come back at the of each chorus, a way of saying “That’s how I wrap up that one, folks!”

0:35, Second chorus: A rhythmic variation, with fancy right hand runs at the end of each half.

1:05, Third chorus: A variation featuring a running right hand line. A good example of the independence of his arms.

1:35, Fourth chorus: Each half begins with descending triplets. Notice how he controls his left hand and plays it louder from 1:45 to the end of the first half.

2:05, Fifth chorus: Talk about independence of the arms—this one blows my mind! While the left hand continues its driving pattern, the right hand plays two things at once, jumping back and forth between the middle register and a higher register.

2:36, Sixth chorus: This is the “shout chorus.” He’s getting ready to wind up, because of the time limitation of the recording. The “shout chorus” usually started high up, like bells, as he does here. But please join me in imagining that he could have easily created ten more choruses, each different from the one before.

His tempo is super steady, almost exactly the same at the end as it was at the beginning. He hits a slight blooper on the very last chord (before the low note that ends it), but nobody cares. The voyage has been amazing!

Please LISTEN, with no distractions around you:

Amazing!

Now, Paul Marcorelles of Paris is known for his accurate transcriptions of the stride piano masters. He sells books and individual solo transcriptions of James P., Fats Waller, Willie the Lion, Teddy Wilson, Jelly Roll Morton and others, as well as early Erroll Garner when he was playing in a stride style.

(Paul has been kind enough to share his latest, newly re-edited transcription of “If Dreams Come True,” exclusively for paying subscribers, below! Also for paying subscribers, I’ve uploaded the other take that Johnson recorded on the same day. It starts off very close to the issued version above, but then goes on differently.)

Somebody took the Marcorelles transcription and made the video below. It’s very instructive to watch the transcription played on this upright piano with Yamaha’s Disklavier moving the keys. It’s the modern version of a “player piano,” which used paper piano rolls while one pumped with one’s feet. More advanced models had a motor and did not require you to pump. They were called “reproducing pianos,” and that’s what we call the Disklavier and other such systems today.

Watching this video, you can almost see James playing. Please notice the left hand from the start—look at the distance between the bass notes and the chords. That’s a cornerstone of the “stride” style. The stride players scoffed at pianists who played a “modified” stride style, where the bass note was an octave or less from the chord. (It has never been noted that was one of the main reasons that they did not respect Jelly Roll Morton’s playing is that he didn’t consistently play stride, but, as was done in his region, he broke it up with octaves and modified stride.) The true stride approach, using big leaps, is much more difficult, especially at a fast tempo. By the way, the tempo on this Disklavier is set to just a bit slower than the recording, which means that you can’t have fun matching them up together. Still, it’s a great way to see what Johnson’s hands are doing!:

I hope this gives you an idea of why Duke Ellington wrote in his autobiography (Music Is My Mistress, pp.94-95) that he was a “disciple” of Johnson, and that, when all the pianists got together to play for each other, “it was me, or maybe Fats, who sat down to warm up the piano. After that, James took over. Then you got real invention —magic, sheer magic. James he was to his friends—just James, not Jimmy, nor James P. There never was another.”

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Thank you to Steven Lasker for research on the song.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.