Jimmie Blanton: Photo & Recordings BEFORE Ellington! Guest Post by Matthias Heyman, 1 of 2 (+Bonus Article)

(Dear Paying Subscribers, at the end you’ll find a rare interview with a friend of Blanton that gives a rare impression of what the bassist was like as a person. Remember, a paid subscription unlocks all bonus items, about 75 of them to date.)

[Dr. Matthias Heyman is a jazz scholar, educator and bassist in Belgium. For his Ph.D. he spent some time in the U.S.A. investigating Jimmie Blanton’s life and music, and his dissertation, in English, is the best work done on Blanton to date. (It will eventually be published as a book by Oxford University Press.) One of his most astonishing findings, following up on information from the late Phil Schaap, is that the bassist recorded in 1937, two years before he joined Ellington! I will let Dr. Heyman tell the story:]

Jimmie Blanton’s First Recordings

by Matthias Heyman

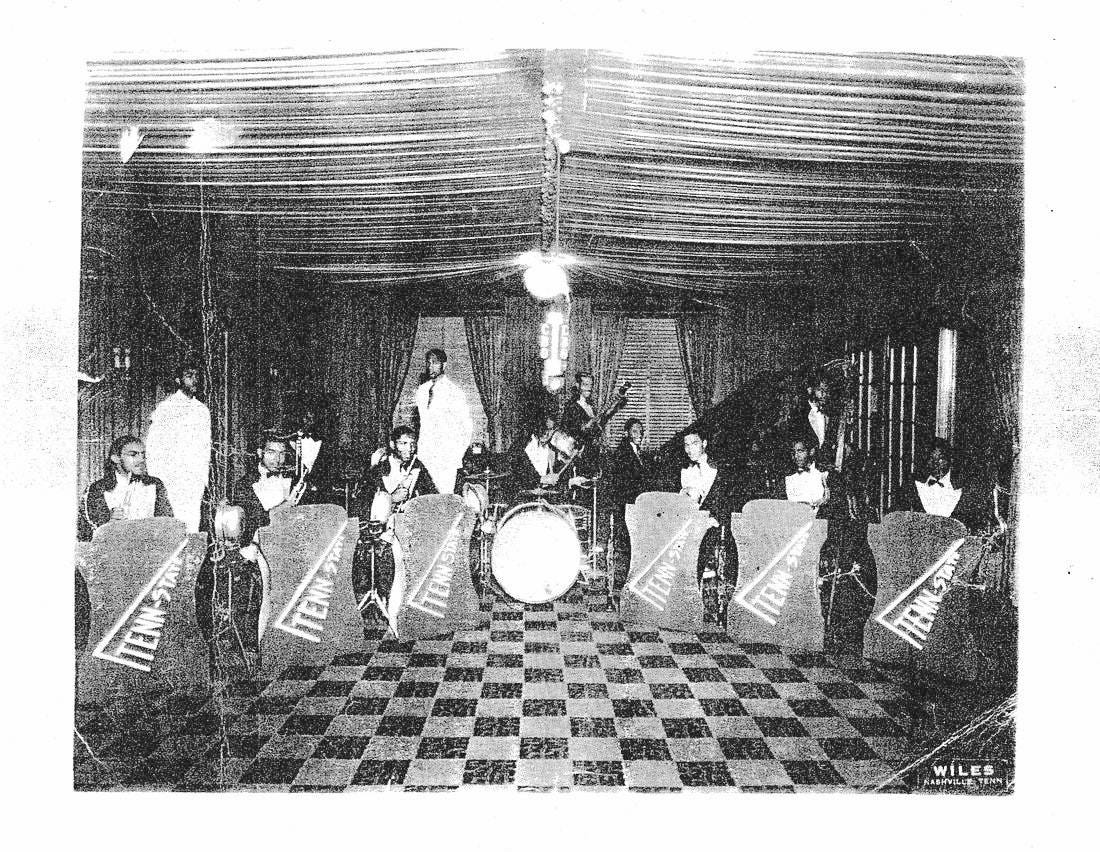

Jimmie Blanton’s musical career wasn’t limited to his two highly prolific years with Ellington. In fact, prior to joining the Duke, he already was an in-demand bassist with a regional reputation in parts of the Midwest and Upper South. Born on 5 October 1918 in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Blanton was raised in a middle-class Black American family with American Indian roots. His mother had made a name for herself as a first-call pianist and band leader in the city’s wider region, and encouraged her children to study music, bringing them along to the musicals, society gigs, and dances where she performed. Jimmie played the violin before switching to double bass in his early teens, and by 1934, although he was still in high school, he was drafted as the bassist of the Tennessee State Collegians, the dance band of Nashville’s Tennessee State College. We thank researcher Ken Steiner for this rare unpublished photo of Blanton (on the right) with that band. (Founding Subscriber Jim Brown made the photo more clear than the original.)

While these early formative experiences were instrumental to his musical development, his professional career truly kicked off in the summer of 1937. That year, Blanton spent part of his summer holidays with his Aunt Alberta in St. Louis, 300 miles to the north of Nashville, in neighbor state Missouri. In The Mound City—one of St. Louis’s many nicknames—he met two former sidemen of the territory band of Alphonso Trent, which he remembered seeing perform in Chattanooga several years earlier: alto saxophonist James Jeter and tenor saxophonist Hayes Pillars. After Trent’s group broke up in 1933, both men co-led their own outfit. The band had quickly earned a strong reputation, and in the spring of 1934, they took up a long-term residency at Club Plantation, St. Louis’s foremost night club. Club Plantation served a “strictly white patronage only,” as it boldly stated in print, for example on this matchbook cover:

But Blanton, always eager to catch some live music, went out to see them when they were playing in nearby Brooklyn, Illinois. Trumpeter Ralph Porter, then a member of the group, recounts:

“During [this performance] a whole team of youngsters came up to … Pillars and said ‘You’ve got to hear our friend play the double bass.’ They went on and on. Eventually Pillars decided to let the youngster sit in … The young cat got up on the stand and Pillars called ‘Nagasaki’ … It was obvious from the first notes that he could play, and how! Pillars called out, ‘Take a chorus!’ The chorus was so fantastic that Pillars shouted ‘Take another!’ and the youngster played even better. He took a handful of choruses and we on the bandstand couldn’t believe what we were hearing.” (John Chilton, “Blanton’s Early Days,” Blue Light 3/4, October–December 1996, p.3. Paying Subscribers, this complete Ralph Porter interview is below as your latest bonus.)

“Everybody just fell in love with him,” Pillars reminisced, and Blanton was immediately offered the bass chair. (Dennis Owsley, City of Gabriels: The History of Jazz in St. Louis, 1895–1973, Reedy Press, 2006, p.75.). He did not decide straightaway, but first went back to Chattanooga to convene with his family, as this meant quitting Tennessee State College. However, joining this band was too good an opportunity to miss, and Blanton took Jeter and Pillars up on their offer. They had always been able to rely upon first-rate bass players, including a brief stint in 1934 by Walter Page, later a Basie side person. Since 1936, Vernon ‘Huck’ King had been the band’s regular bassist, but he was given his two-weeks’ notice when Blanton joined. (Later, in 1943, King in turn succeeded Wendell Marshall, Blanton’s cousin, with Lionel Hampton—and Marshall was playing Jimmie’s bass!) Now, the group counted one of the country’s most promising bassists in their ranks. For approximately the next two years, Blanton called St. Louis his home.

Blanton was still using the smaller bass he had been playing since his early teens. But this instrument, which had served him for several years, hardly met the professional standards. Jeter and Pillars took their new bassist to the St. Louis music store to acquire a regular upright bass, and he bought the 1926 Josef Novotny he was to play for the remainder of his career. It seems the instrument was direly needed, as the Jeter-Pillars band was about to make their first and only recording session. In late August of 1937, the twelve-piece group (a four-part rhythm section, three woodwind players, three trumpet players, and two trombonists) travelled to Chicago to wax four tracks for the budget-priced Vocalion label: “Make Believe,” “I’ll Always Be in Love with You,” both recorded on 25 August, and their theme song “Lazy Rhythm,” and “I Like Pie, I Like Cake (But I Like You Best of All),” the following day.

This session, Blanton’s very first, and the only one prior to joining Ellington more than two years later, allows us to hear the eighteen-year old bassist at an earlier stage of his musical development. However, this has been overlooked because all discographies list King as the bassist on these four sides. But four band members—Hayes Pillars and his brother Charles, guitarist Floyd Smith, and Blanton’s successor in the band, Billy Hadnott—stated that it was Blanton (Pillars in his oral history, pp. 56-57; Smith in Jas Obrecht, “Electric Guitar Pioneer Floyd Smith on 1930s Jazz and Django,” Jas Obrecht Music Archive, 27 July 1979; Hadnott cited in Peter Vacher, Swingin’ on Central Avenue: African American Jazz in Los Angeles, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015, p.201). It’s also worth mentioning that fellow bassist John Simmons, also born in 1918, said that “I Like Pie” was the first time that he heard Blanton on a recording. (Simmons oral history p.46.)

Despite the witnesses who say it was Blanton, it is important to study the recordings of Vernon King to be certain that he could not be the bassist on the recordings. King certainly was no slouch, appearing as the bassist in bands led by Sammy Price, Earl Bostic, and Lionel Hampton throughout the 1940s. Still, on record he is seemingly never featured as a soloist, in spite of having “bass-friendly” leaders such as Price (who showcased Oscar Pettiford in 1944) and Hampton (who spotlighted Charles Mingus in 1947). Wouldn’t King be given the opportunity to wax a few featured spots if he excelled at soloing? Besides, his accompanying, primarily straightforward walking bass lines, is steady, sturdy, and bouncy but otherwise unremarkable. In short, I did not hear anything that particularly resembled the bass work on the Jeter-Pillars session, and he definitely does not sound like the bassist on “I Like Pie, I Like Cake,” the record that showcases the bass the most prominently. In fact, the bass parts on this particular side already bear some typical characteristics of Blanton’s style, albeit in an embryonic state. This will be the focus of my discussion in part two of this study.

[Thank you Matthias. Next time we will see Part Two, with audio clips.

All the best,

Lewis]

P.S. Paying Subscribers, keep scrolling down for your bonus article.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.