(Paying Subscribers, at the bottom you’ll find a fascinating article by Dr. David Chevan about the importance of written music in early jazz.)

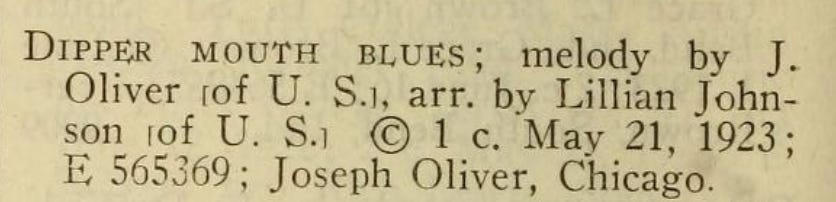

Let’s continue our close listening to these acclaimed recordings from 100 years ago. In Part 1 we gave some history of the band and started listening to “I Ain’t Gonna Tell Nobody.” We dived deep into that recording in Part 2, and listened to the band’s pianist Lil Hardin Armstrong in Part 3. Today, we will start to explore the most famous, and most imitated, piece in the band’s repertoire, “Dipper Mouth Blues.” That is how the title appears in the copyright info and on the original 78 r.p.m. labels. But it is most often written as “Dippermouth Blues,” and when quoting others below, I will not change their formatting.

Louis’ nickname since he was a kid had been “Dipper Mouth,” as in “Big Mouth”—not completely flattering, but it was all in fun. Drummer Baby Dodds, in his memoir, says that Louis was also called “Dipperbill” and “Blathermouth”—those names are kind of rude, but I haven’t seen them mentioned anywhere else. As you may know, in 1925 the song became known under the alternate title “Sugar Foot Stomp.” That will be the subject of a separate essay.

This was a blues in the key of C concert. For years it was issued on various LPs playing in Bb or B, that is, at an incorrect speed—a common problem with 78 rpm discs and players. If you go to my Spotify playlist (or create one in another streaming service), and just play the beginning of each reissue of “Dipper..,” you will be amazed at how many different starting pitches you will hear as you go down the line! But these days it is correctly transferred in C.

The lead sheet was mailed to the Library of Congress to be deposited there to register the copyright, so these are known as “copyright deposits,” or simply “deposits.” The sheet was handwritten by pianist Lil Hardin. (Actually, she was Lil Johnson at the time, and soon to be Armstrong. For simplicity, I sometimes use her birth name Hardin.) She regularly wrote pieces out for the band members. Sometimes she also wrote out parts of the arrangement (that is, who plays what and when), and in such cases she usually had participated in creating that arrangement. In fact, she’s credited for that in the copyright listings for six or seven of the 1923 Oliver titles, including this one. By 1926, when she began playing on Louis’ Hot Five recordings, she was a full partner in the music making—writing tunes, creating complete arrangements, and so on.

As you can see below, the Library stamped the date that they received it, May 21, 1923. The first line of music is the introduction, and the next three lines are the 12-bar blues theme. (The first note of the second measure in the second staff should be Eb.) The fifth staff, which begins with a fancy repeat sign, shows roughly what the band plays while Johnny Dodds takes a clarinet solo for two choruses:

(You might find this page online, signed “Turk Murphy” at the bottom. That’s not on the original. Murphy, a trombonist born in 1915, was involved with trumpeter Lu Watters from 1939 onward in recreating the Oliver recordings. He got a copy many years later—probably in the 1970s—and signed it.)

Why did they send it to the Library of Congress in May 1923? They had already recorded the piece on April 6 for the Gennett label, and would record it again on June 23 for Okeh. And in the U.S.A. a work is copyrighted by default—that is, by the mere fact that you wrote it down. But registration provides many benefits, and most musicians were in the habit of sending their tunes to the Library, either before or after they recorded them. (One doesn’t always know which tunes will get recorded until the session is over.)

The top right says “by Joseph Oliver.” That’s Oliver’s own handwriting, not Lil’s. And the copyright is in his name. Lil is credited as an arranger in the copyright listing, possibly for the stop-time clarinet choruses that she wrote. She is listed under the name Johnson, because she was separated but had not yet divorced her first husband James “Jimmy” Johnson, an aspiring singer. Her name was on the form that accompanies the deposit. For example, there is room on the form to list more than one composer, and to specify each one’s role, as in “J. Oliver, melody,” “Lillian Johnson, arrangement,” or, when there are lyrics, “words.”

An arrangement can be copyrighted by permission of the composer, as of course was the case here. That is to say, someone else cannot make their own arrangement and send it in for copyright registration, without getting permission from the composer(s), and listing them on the chart, and usually paying them a licensing fee. Unlike the composer, who gets a royalty every time the song is recorded, the arranger only gets a royalty if that particular version is re-recorded.

Arranging in small groups is one of the least studied aspects of jazz. Somehow it is often taken for granted that everybody just knew what to do, or that arrangements are always worked out by the musicians together, or that it just doesn’t matter. But as I’ve shown in my series on Billie Holiday’s arranging, it matters greatly. From 1923 onwards, Oliver created some of his own arrangements, and he is sometimes credited for that in the copyrights. Jazz historian and Armstrong expert Ricky Riccardi directed me to an interview of Lil Hardin by William Russell, a prolific researcher of early jazz, conducted July 1, 1959, at her home in Chicago. Here is the relevant audio portion, and below is my transcription of what she says:

Hardin: Everything we played was organized so well under Oliver. You noticed all the numbers we played, we’d—everybody would know what they were supposed to do? We used to rehearse!

Russell (overlapping): Were ever—Were those numbers ever written out?

Hardin: No, no, no—but we rehearsed.

Russell: They rehearsed.

Hardin: There was no fumbling around for the introduction or the ending. We knew what we were going to start with and how we were going to end. And Louis and Oliver knew when they were going to make their solos—we were a well organized band.

And as I mentioned above, Lil herself was a very capable arranger. But Louis is not known to have done much arranging, at least not this early. On the few pieces he wrote, he concentrated on the melody line. In fact, several of his 1923 copyrights list Lil as the arranger.

Even though it’s important information, arrangers are not usually credited on record labels, only composers. But when the recordings of “Dipper Mouth” came out, the labels of the 78 rpm discs (Gennett 5132 and Okeh 4918) listed two composers, Oliver and Armstrong:

Clearly, Armstrong must have had something to do with writing the song, or his name would not have been added. In fact, there are some historians who believe that Armstrong alone wrote this blues, and that Oliver took his “leader’s prerogative” to say, “If I’m going to record this for you, I need to get some of the royalties.” For one thing, Oliver was known to have done that with other songs and other musicians.

Another point supporting Louis as the sole composer is that Russell interviewed bassist Bill Johnson around 1938 for the forthcoming book Jazzmen, an important early history of the music. Russell did not record those early interviews, but he typed up a summary after each one. On his summary of the interview with Johnson, he wrote: “Louis composed the Dippermouth at the Royal Gardens at that period. Louis was called Dippermouth then.” The Royal Gardens, a large nightclub at 459 East 31st Street in Chicago, had been re-decorated and re-named the Lincoln Gardens. It was the band’s home base from June 1922 through the end of 1923, although they did play elsewhere on occasion.

In order to build up Armstrong’s case, it has also been stated that multi-instrumentalist and composer Don Redman said that when Armstrong joined Fletcher Henderson’s band, Louis had a book of handwritten tunes that included “Dipper Mouth Blues.” But that is not what Redman said. The original source for this is jazz historian and musician Leonard Feather, and in The Book of Jazz, he reported what Redman told him in 1957:

Shortly after Louis Armstrong joined the band, King Oliver sent him a little notebook with [staff] lines drawn on it. Together they had written a lot of things. Louis gave it to me and said, “Pick out anything you want and make it up [arrange it] for future use.” They had things like “Cornet Chop Suey” and “Dippermouth Blues,” which later became known as “Sugar Foot Stomp.”

(A similar quote from Redman is in Walter C. Allen’s book Hendersonia, from an unpublished interview with Felix Manskleid.)

So Redman certainly did not say that Armstrong wrote “Dipper Mouth” alone, rather that Armstrong and Oliver together had written “a lot of things” including “Dipper Mouth.” In short, this is not evidence of Armstrong’s authorship, but instead supports the idea that he and Oliver wrote it together, as listed on the record label.

Also, Ricky Riccardi shared with me a transcript from an interview with Armstrong by producer George Avakian, taped in 1953. In it, Armstrong indicates that he and Joe wrote this together, and then Joe named it after him. George said, “I noticed on the old labels they put down ‘written by Oliver and Armstrong.’ So you worked [it up] together after you came in the band?” Louis replied, “Yeah, after we got together. We’d make up those things and then he’d put me [my name] on it.” (Ricky has published two volumes of his major Armstrong biography, and you will be happy to know that he is working on the third, final volume, to be published by Oxford University Press in 2025.)

Baby Dodds recalled that “‘Dippermouth Blues’ was a number that the whole band worked out. Each member of the outfit contributed his own part…Everybody had his part in composing the thing.” After a new melody was introduced, usually by Oliver, it was standard practice for the others to make up their own parts, within the established guidelines of the genre. In fact, we will discuss that process in the next essay. So that in itself is not notable, but this does support the idea that there wasn’t just one composer.

However, to add to the confusion, there is also evidence against the idea that Armstrong was involved in creating the song. Ricky also steered me to a 1958 audio interview of multi-instrumentalist Manuel Manetta, conducted, again, by William Russell. Manetta said that Oliver used to play “Dipper Mouth” in New Orleans when they were both in trombonist Kid Ory’s band. Below, Manetta distinctly remembers playing the diminished chord introduction alone on piano, before the band came in, and he hums it accurately (but in the key of F):

(I am very thankful to Robert Ticknor, Senior Reference Associate, at The Historic New Orleans Collection, an independent museum and archive, for the Manetta and Bill Johnson interviews. Armstrong scholar Thomas Brothers provided a copy of the Johnson as well.)

In the following segment, Manetta mentions playing it with Ory, and says that he recently saw a white band on TV that shouted “Oh, play that tune!,” and that that was clearly a take-off on the shout “Oh, play that thing!” from “Dipper Mouth.” (We will hear and discuss that shout in one of the next posts.)

So Manetta’s memories are very specific, and should be taken seriously.

But how do we explain and reconcile all these seemingly conflicting accounts?

Some day, I’ll offer an essay about research techniques. But for now, let me say that one of my rules is to assume that everybody is doing their best to tell the truth, despite memory problems and so on. When two stories appear to contradict each other, my first question is not, “Who’s telling the truth?” Instead, I ask: “Does it have to be one or the other? Could they both be true?”

In this case, I think that all the evidence taken together can be explained in this way: In New Orleans, the Ory band with Oliver and Manetta played a blues, but not what we know as “Dippermouth,” and certainly not with that title. Let’s assume that it was a different blues in C. After all, the piano part would have been the same for any blues in C. But this blues had a diminished chord introduction, and when Manette heard “Dipper Mouth,” he recognized that introduction. Towards the end of the piece (or possibly another piece), one of the musicians would shout, “Oh, play that thing!”

A few years later, in Chicago, Armstrong came up with the blues riff which is the main melody of “Dipper Mouth Blues.” Then Oliver and Lil did some arranging of it. Joe said, “Let’s add that diminished chord introduction that we used on a different blues back in New Orleans.” And—we’ll discuss this later—he may have even suggested the shout near the end. It was Lil’s idea to have the clarinet take a solo over the stop-time passage, and she wrote that into the leadsheet for deposit.

Then Oliver gave the song its name, and decided that for all of his contributions, and for being the leader, he deserved the copyright and a co-credit on the record labels! OK, I admit that maybe Joe went too far on that point. But please note that later on, Louis very openly disputed the authorship of several pieces on which he said he should have gotten credit, including some on which Lil was credited. But he never questioned “Dipper Mouth.” That is significant. Also, Oliver did not arbitrarily claim every composition. In fact. “Weather Bird Rag,” which was recorded the same day as the first “Dipper..,” and was released on the other side of the Gennett 78 rpm record, is credited to Armstrong alone.

BOTTOM LINE: The only explanation that agrees with all the evidence, in my judgement, is that Louis Armstrong wrote the main theme of “Dipper Mouth Blues,” “King” Joe Oliver and Lil Hardin provided the arrangement, and Oliver came up with the title.

(By the way, the blues pianist Little Brother Montgomery recorded a piece he called “Bob Martin Blues” (or possibly Bob Morton), and in later years he said that Oliver got “Dipper” from that blues. Montgomery did not specifically say that he composed that blues, but on most releases it’s credited to him, and he is the only one who recorded it. However, he is not known to have crossed paths with Oliver, and he did not record “Martin..” until 1960, many years after Oliver died. Besides, on that first recording, the theme does resemble “Dipper,” but when he later re-recorded it, the “Dipper” theme was entirely gone. So I think it’s fair to discount this claim.)

Now, let’s go to the music. In the next essay, we’ll listen to the clarinet solos by Johnny Dodds. After that, we will listen to the two recordings of “Dippermouth Blues” complete, and we’ll focus on both cornetists, and that shout, among other things.

All the best,

Lewis

(Paying Subscribers, scroll down for an article about the importance of written music in early jazz, contrary to many stereotypes.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.