(Paying Subscribers: The First Book of Jazz by Hughes is at the bottom as your bonus, plus one of his favorite recordings, the 1953 protest number, “But Officer.” Thank you for your support!)

You probably know that the brilliant author Langston Hughes was a serious jazz fan. He wrote about jazz, and he read his poetry on recordings with the bands of Red Allen and Charles Mingus, and on TV with Canadian musicians. He wrote a child’s introduction called The First Book of Jazz, and recorded an LP to go along with it. And there’s much more evidence of his love of jazz.

Hughes was celebrated in his lifetime and his work is certainly well documented. His writings have been collected in sixteen well-researched volumes, which I highly recommend. (It appears that eighteen volumes were initially announced, but that the series finished at sixteen.) And yet—what about the over 1200 pieces that he published in the the Chicago Defender, an important Black newspaper? In the preface to Volume 9 of his collected works, the editors explain, “Because of space and cost limitations, however, omissions were inevitable. Hughes was a weekly contributor to the Chicago Defender for more than twenty years, writing hundreds of columns on disparate topics. These journalistic writings have not been included.”

Beginning irregularly in 1926, Hughes spoke passionately in the Defender about injustice and civil rights, and discussed events of the day when they were still current news. At other times, he posted short stories or poems. Starting on November 21, 1942, he wrote every week for the paper, until 1962. To be fair, many of Hughes’ writings for the Defender were stories that later appeared in such books as The Best of Simple. And Christopher De Santis collected about 100 of Hughes’ columns in a book. Perhaps a dozen more appear in various volumes of the Collected Works. But, completist as I am, I wanted to study all of his writings for myself, not selected by someone else, and in the order published, not organized by topic or genre. So around 2016, I tasked my graduate student and research assistant Michael Li with collecting every piece written by Hughes in the Defender, which had been digitized. He did a very thorough job, and I will periodically share them with you, a few pieces at a time, in what will surely become the longest series within my Substack writings. Hughes also wrote occasionally for other publications, such as The Crisis, Phylon and The Nation. Some of these have been collected into books, but not all of them. Presenting those could be a project for another time.

SO—Let’s begin. Here is my plan: Again, my focus is on the 1200-plus pieces authored by Hughes starting in November 1942. (Please note, the Defender database automatically provides the date at the top of every article.) I will include everything from then on, regardless of whether it has ever been reprinted. Before 1942, I will only include writings that have never been collected. Also, starting in 1925, his name often appears in the paper, about 2500 times, not as author but with regard to his winning prizes, giving readings, and other news, so we won’t be looking at those. (If you have a different idea of how I should proceed, just let me know.)

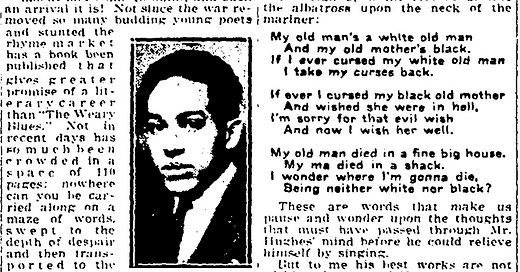

However, I do want to begin with the first substantial piece about him, even though he didn’t write it. It’s an enthusiastic review of Hughes’ first poetry collection by Dewey Roscoe Jones. Forgotten today, Jones (1899-1939) earned a B.A. (U of Michigan, 1922) and M.S. (Columbia U, 1932) in journalism. He started as a reporter for the Defender in 1923 and soon became an editor. Jones raves about Hughes’ book, calling it a gem that should be in every library. He reprints a few of the poems, and he comments that white people will surely like the ones that employ “Negro” material such as jazz and blues. When white people like your work, Jones knowingly observes, “You become their pet” and they “make you a fad.” Jones “gets” the irony in this, and in fact he prefers Hughes’ other works, those that are not about “his color.” Here’s his review:

The book had an introduction by Carl Van Vechten, who, as you may know, was a white man who became a passionate supporter (and some would say exploiter) of Black culture. He was also a prolific photographer who created many color portraits of notable Black people. Here is his beautiful portrait of Hughes:

Hughes’s own first contributions as an author to the Defender were poems. The earliest one, “Song,” is shown below in its first appearance. The Defender published it again on September 25, 1926 with an extra heading indicating that by then it had appeared in The New Negro, the important anthology book edited by Alain Locke:

But the following two poems have never been reprinted, to my knowledge, not even in the Collected Works. “Lost Man” was printed on the Defender’s poetry page Lights and Shadows, which was for a time edited by Dewey Jones. It’s one of many poems that Hughes wrote in the form of a blues lyric, three sentences per stanza:

And the poem below, also never again printed as far as I know, was dedicated to his early patron A’Lelia Walker, daughter of the famous Madame C.J. Walker. Madame Walker is usually listed as the first self-made (that is, not inherited) female millionaire in the U.S.A. But it’s said that there may have been others before her whose finances are not as well documented, including the Black entrepreneur Mary Ellen Pleasant. When Madame Walker died in 1919, A’Lelia took over the business until she herself died in August 1931. As the poem indicates, she died in the middle of a party, of a cerebral hemorrhage (a type of stroke). Hughes wrote this in her memory, and it was read, by someone else, at her funeral:

The next contribution to the newspaper by Hughes is his poem “The Cross.” Not only has this been reprinted many times, it appears in the Jones review above, at the top of the second column (“My old man’s…”). So, as per my stated policy, I won’t repeat that here.

This series will continue, more or less frequently, depending upon your response to this first installment. Let me know!

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Paying Subscribers: The First Book of Jazz by Hughes is at the bottom as your bonus, plus one of his favorite recordings, the 1957 protest number, “But Officer.”{ Thank you for your support!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.