I’ve said it before: Of the people who had the biggest impact on jazz, Lester “Pres” Young (1909-1959) is, sadly, the one whose music is the least known. His music of the late 1930s and early 1940s probably had as much impact on all of jazz (not only on saxophonists) as Bird and Trane did later—including his impact on young Bird and Trane themselves! But the experience of saxophonist Kevin Sun is typical of today’s listeners. He writes: “The first Lester Young I ever heard was Lester Young with the Oscar Peterson Trio, recorded in late 1952. It was the only Lester Young CD available at my local Barnes & Noble in New Jersey.”

That is a key point. Because the Verve recordings are generally the easiest to find, and, being from the 1950s, they have the best sound of Young’s recordings, those are the ones that most people get to hear. Sun continues:

I picked it up because I'd read that Young was a major influence on Stan Getz. At the time, I recall listening to it repeatedly but not particularly liking Young's playing, notably the wispy, reedy tone and intractably sharp intonation on the ballads. I also couldn't hear much of the resemblance as described by jazz writers about the essential debt that Getz owed Young.

I hadn't heard the iconic early recordings with Basie, which had cemented his legacy and directly influenced Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, Dexter Gordon, and so many others in the late '30s and [early] '40s. Once I finally checked out those recordings…Prez's influence on the artists I mentioned became immediately clear: the buoyancy and momentum of his lines, the ease and confidence of his zigzagging phrases, and the unmistakable joy in his sound.

The good news is that Sun went on to explore many other recordings by Young, and in fact he has done some of the best analysis of Young’s music, along with Ethan Iverson’s extensive series. That’s refreshing, because most musicians and fans hear a few minutes of the Verve tracks, assume they’ve “got it,” and move on to other things. But with any artist, and especially an artist like Pres, whose style changed dramatically throughout his career, that is terribly unfair. It would be like hearing one Coltrane recording from, say, 1955—or one from 1966, for that matter—and assuming that you’ve now “got” what he was all about.

Let’s hear excerpts of Pres in 1939 (the Basie record “Jive at Five”), 1940 (Basie’s “Broadway”), and then, at 0:43) in 1958 (“Rompin’” on Verve):

Honestly, would you even know that the last one is the same person, if I hadn’t just told you?

There are two ways that I could proceed at this point. One option would be to illustrate how and why Young’s early recordings were “better” than his later ones. But I don’t want to do that, because I don’t believe that. My first book, a study of Young’s music published in 1985, was dedicated to demonstrating that his style had great validity at all points of his career. BUT—and this is a key point—he did become less consistent by the 1950s. For example, I do not consider “Rompin’” to be a good example of his work. He was clearly not in good shape.

In short, I would feel safe telling you to listen to any and all Pres that you can find up to, say, 1942. But for later material, especially from the ‘50s, unless you’re going to hear everything (as I try to do with all artists), I would rather that you get recommendations from a knowledgeable person.

So, let’s do that. To start with, here are a few of my own favorites from the ‘40s and 50s:

By 1944, before he was drafted, Young’s tone had already become much darker, his vibrato thicker, his ideas very bold and striking. My musician students invariably find this era of Pres to be very appealing, as did the young Rollins. (He has named a 1944 Pres recording, “Jump Lester Jump,” among his early influences.) Here is “After Theatre Jump” (March 1944, the master take), by a Count Basie small group. Everybody plays with such fire, and Jo Jones is so brilliant throughout, that I’m sharing the whole piece with you. The other musicians are Buck Clayton, Dicky Wells, Freddie Green and Rodney Richardson (bass). Young’s solo is at 2:15. Notice how he starts by building up from a little riff:

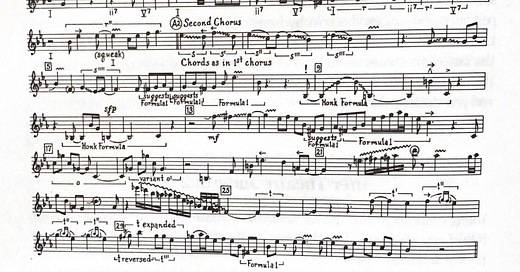

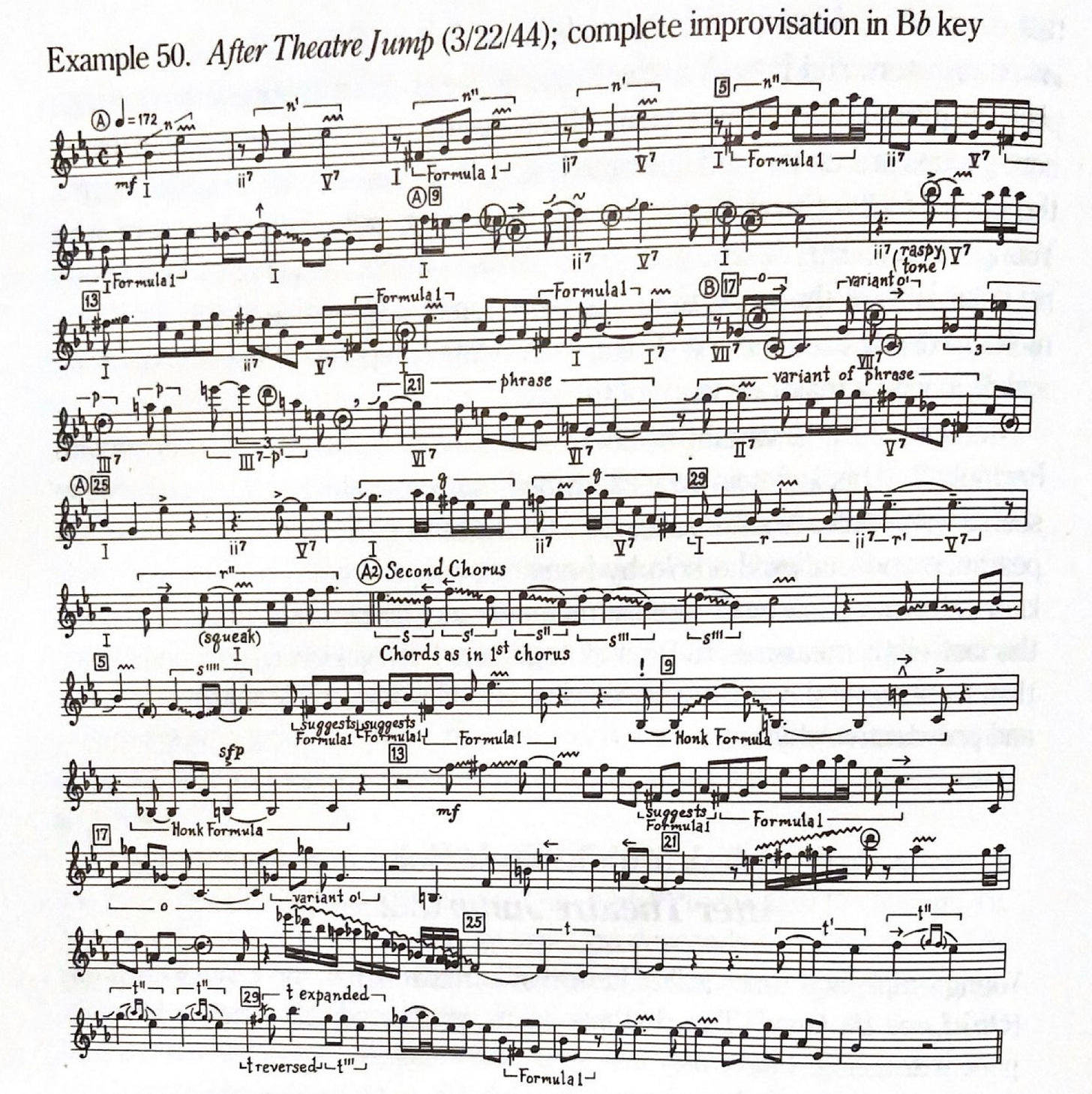

Below is how I transcribed it back in 1979, and published it in in my first book in 1985. I wouldn’t mark it up the same way today, but at that time I wanted to show how Young often worked on a musical idea or riff a few times before moving on. If you wish, listen again with this in front of you:

So, that was before the Army. Now, at his very first recording session after leaving the Army, in December 1945, he created a profound improvisation on “These Foolish Things,” with Dodo Marmarosa (p), Red Callender (b), and Henry Tucker (d). I have no idea why this powerful and expressive, fully improvised performance is not as celebrated as “Body and Soul” by Hawkins:

What a deep ending! This is more proof, if any were needed, that he was not “destroyed” by the Army, not “a shell of his former self,” nor any of the other clichéd statements favored by authors. (I’ll post a separate essay about Pres and the Army, later.) Subscriber Jim Gerard reminded me that pioneer “vocalese” singer Eddie Jefferson put words to this solo, which can you listen to here.

Moving ahead, in February 1950 a fan recorded Young at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, with Kenny Drew on piano, Aaron Bell on bass, and Jo Jones on drums. Among the many titles that were eventually released was a performance of a new song, “Destination Moon.” (I have not found any connection between this song and the film of the same name that was released in June 1950.) Nat “King” Cole recorded the song in December 1950, and Dinah Washington in 1962, among others. (Illinois Jacquet’s 1947 recording of the same name is a blues, unrelated to this AABA song. All issues of this are in Gb, but another Pres performance of this tune, from a 1952 radio broadcast, is in F, and for this and other reasons I have adjusted the key to F.)

In this “live” setting, at a casual gig not meant to be preserved—in fact, someone whistles during the opening theme—and without the benefit of extra takes, Pres creates a continuous stream of beautiful melody (I faded it out after Young’s solo):

It’s one lovely idea after another. I can’t stop singing to myself the bridge section excerpted below (from 1:18 in the above clip), as though it were on “repeat”—I guess it’s an “earworm” for me. Notice that, even in 1950, Pres had a unique kind of melody and phrasing, different from all his protégés, and very different from what he did in, say, 1940. For example, listen to the delightful “sing-songy” ideas he plays from 0:03 to 0:10 below, over what is basically a C minor chord going to Bb major—and the way that contrasts with the openness of the next phrase. That is, he was not “trying to play like he did in the ‘30s but failing.” Instead, he was working on a new concept, and very successfully. Listen please:

(By the way, this was originally issued on Charlie Parker Records. Around 1982, I reached out to the current owner of that label, who kindly shared with me cassettes of everything he had at hand, including unreleased material. To this day, all discography listings and unissued recordings of Young at the Savoy Ballroom in 1950 come directly and only from my sharing those cassettes with other researchers.)

Now let’s jump ahead to Young’s European tour in late 1956. In Frankfurt, Germany, on November 9, he performed at a club called the Jazz Keller (Cellar), for an audience that included American soldiers. Bassist Al King and drummer Lex Humphries were in the Army band at the time. The pianist was wrongly identified on the original LP—it was in fact Lasse Werner from Sweden, who often worked in Germany then. Pres was in great form, and this audience tape captures his longest solos ever recorded. On his best-known composition, “Lester Leaps In,” he is bursting with expressive ideas, including some striking sound effects. Let’s listen, starting right after the theme statement:

Next time, we’ll hear some ‘50s Pres selected by journalist/saxophonist Zan Stewart, we’ll learn about Pres’s mouthpieces from saxophonist/educator Jeff Rupert, and we’ll come to some conclusions about Young’s later work.

All the best,

Lewis

Jim, the December '45 sides were done for Aladdin, with Vic Dickenson on all but "These Foolish Things". Lots of reissues available.

You’re welcome, Lewis. Right—“Baby Girl.”