This series about Miles Davis’s composer credits will have many installments, and I’ll be jumping around chronologically. I’ve had several requests to discuss one particularly interesting case, “Nardis,” so I’ll focus on that now.

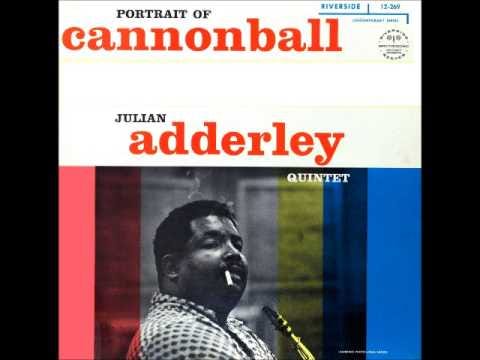

On Tuesday, July 1, 1958, a quintet led by saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley recorded music that was later released as the album Portrait of Cannonball. The last tune on Side Two was, as producer Orrin Keepnews explained in his liner notes on the back, “the Oriental-flavored Nardis, one of Miles Davis' rather infrequent compositions, specifically written for Cannonball's Riverside debut.” (This was his debut album as a leader for Riverside Records. He had previously recorded as a leader for other labels.)

Bill Evans was the pianist on the album. In Peter Pettinger’s biography of Evans, he quotes from a published interview: “[Davis] came along to the studio with it," Evans recalled. "It was certainly different; it moved differently, and you could see that the guys were struggling with it. Miles wasn't happy either, but after the date he said that I was the only one to play it in the way he wanted. I must have helped his royalties over the years, because I have never stopped playing it. It has gone on evolving with every trio I have had." (Quoted by Pettinger from Brian Hennessey, "Bill Evans: A Person I Knew," Jazz Journal International, England, March 1985.)

Notice that Bill says that Davis was in the studio for the recording session. Keepnews confirmed that, and added more detail: “Miles Davis, who had composed ‘Nardis’ for Cannonball, showed up at the studio to hear the tune recorded. Miles was in the booth the whole time on the first of the two days we had scheduled for recording, and Blue [Mitchell] was totally freaked. I remember coming back and cutting the entire album on the second day” (Bob Blumenthal, essay for Mosaic's The Complete Blue Note Blue Mitchell Sessions). In other words, there was a first day of recording, presumably Monday June 30, but they produced nothing usable that day so that day is not usually listed. (It is mentioned in Chris Sheridan’s Adderley reference book.) Fortunately, Keepnews had scheduled two days, and they got everything done the second day. By then Miles was not needed, because he had explained the piece and coached them through it on the first day.

Mitchell had recorded a number of times since 1951, mostly backing up such soloists as saxophonist Earl Bostic, but also as a soloist on a 1952 date led by altoist Lou Donaldson. But this was “big time”—Adderley had convinced Keepnews to record Mitchell’s first date as a leader, which was scheduled right after this one, July 2 and 3. So he was nervous anyway, and having Miles there made him more so.

Two takes of “Nardis” have been released. (They are labeled Takes 4 and 5 because Riverside, like Blue Note, numbered takes for the entire session, not separately for each tune. So the two takes of the preceding tune, Gigi Gryce’s “Minority,” were numbered 2 and 3.) Adderley and trumpeter Blue Mitchell basically treat it like a bop tune, which it is not. Mitchell had some difficulty playing on the unusual chord sequence, as you can hear, for example, in the originally unissued first take. His solo begins at 2:27 and he hits an awkward couple of notes at 2:40:

Even though the sax and trumpet “made the changes” (followed the chords) on the issued second take, I think Davis was looking for something else. He liked that Evans did not treat it as a standard tune, but got into the moody quality of it.

Evans clearly had an affinity for the song, and he continued to perform and record it over the years. There are over 40 versions now available. Many were not intended for release—no artist or label would purposely release so many versions of the same tune. Most were issued after he died, some on bootlegs and some on official albums. (And in fact, there are so many “live” Evans albums out now that other songs also exist in many versions.) At performances, he tended to introduce it in words similar to what he said in the interview above. For example, let’s see what he said at a house concert and interview in Helsinki, Finland that was professionally filmed for television. I also included his piano introduction and theme statement leading up to the bass solo. My transcription of his words is below the video:

Bill says, “Maybe we can finish up featuring everybody in the trio with a Miles Davis number that's come to be associated with our group, because no one else seemed to pick up on it after it was written for a Cannonball date that I did with Cannonball in 1958. He asked Miles to write a tune for the date, and Miles came up with this tune; and it was kind of a new type of sound to contend with. It was a very modal sound. And I picked up on it, but no one else did. The tune is called ‘Nardis.’”

There is new information here: Bill says that Cannonball asked Miles to write a tune. It didn’t happen by chance or by magic. Keep that in mind as we proceed.

Here is Evans again, with a similar spoken introduction, in a TV broadcast from the Maintenance Shop, a jazz club in Ames, Iowa, from January 1979. Over the years his piano solo at the beginning grew longer and longer, until it became a major musical statement every time. If you have 4 minutes available, they would be well spent watching this video up to the theme statement (at least):

As you can see, on the face of it, there is no reason to question the authorship of “Nardis.” It has always and consistently been credited to Miles, by Bill Evans and by everyone else. And we know that Miles came to the studio, presumably not just to listen, but to supervise the recording of his composition. Overall, it’s pretty much an “open and shut case” (that is, a clear and not debatable case). One of the first rules of research is that when all the evidence points in one direction, that is the correct answer, unless very powerful evidence to the contrary shows up. And the evidence points to Miles.

So why do I even bring up the question of who wrote “Nardis”? Because there is a strong and persistent rumor that the piece was written by Evans. The story goes that Bill wrote it, but sold it to Miles (presumably because Bill needed money, for drugs or whatever). I will tell you from the outset that in order to displace all the evidence that Miles wrote it, there would have to be very strong evidence in favor of Evans—and there is not.

For one thing, how would this even have worked? One would have to believe that Miles and Bill met privately before the session, that Bill presented Miles with his handwritten leadsheet, that Miles then re-wrote it in his own handwriting, and that Miles then reached into his pocket and handed Bill some cash. Then, during the first day of recording, Miles was present, introduced the tune as his own and supervised the recording of it, without him or Bill letting on that they had a secret deal. This whole imaginary scenario is ridiculous. What’s more ridiculous is that people imagine that Miles gave Bill a lot of money for this unknown tune. The usual advance was $50—that’s all!

But to satisfy those people who are skeptical that Miles wrote it, in the next post I will look closely at all of the arguments that have been raised. It’s a long post—far too long to include here—but I’ll post it sooner than usual so that you won’t be kept in suspense.

All the best,

Lewis

Part of the problem causing Bill Evans to be credited with writing “Nardis” is due to the laziness of some record labels and artists about researching the composer and publishing company of songs, the other is the numerous bootlegs that credit Evans as composer of the song.

The same issue holds true for Denny Zeitlin’s “Quiet Now,” long a part of his repertoire but obviously never claimed by Evans as his piece. Yet the numerous live bootlegs crediting Evans as composer plus sloppy research for several recent historic releases of Bill Evans repeat this error.

If no one else associated with a release is going to do research about proper composer credits, shouldn’t the liner note writer take that responsibility? That is something I have always done since I began writing liner notes years ago and I have found various mistakes on nearly every release that I have worked on, not just composer credits, but also wrong song titles, songs omitted from medleys, incorrect spellings, missing instruments or co-composers and for historic concerts reissued, incorrect personnel and recording dates.

Thanks for this series, enjoying it very much. As you've noted, Evans acknowledged Miles' authorship of Nardis a number of times - the case that is more controversial to me (which I trust you'll get to) is Blue in Green for which Evans did claim authorship with the apocryphal story that when Evans confronted Miles, Miles gave him $25 (or something to that effect). Thanks for the great research and exposition. (And a sidebar thanks to Ken Dryden for the great work he's been doing too!)