(Hello Friends! I’m sorry for the delay, but as it turned out, this post took a long time to prepare, and as you’ll see, it required a lot of research, using a wide variety of sources. Here we go:)

I hope that, after reading this, people stop making fun of Miles for ruining his own voice. As I’ve mentioned before, I have found that most people don’t want to give up their stories, even when they’re proven wrong. But it’s indeed wrong to say that about Miles, as I’ll show.

As I said in Part One, Miles told Steve Allen on national television, “Had an operation on my throat.” It’s a bit hard to hear, but I believe that’s what he says. (Some people told me that it sounds like “Gonna have an operation on my throat,” but it doesn’t sound like that to me, and that would have left people wondering why his voice was already hoarse.) So, his first surgery to remove nodes and repair his voice was likely not long before the TV show, say in October or November, 1955.

But this was only the first of several attempts to get his voice back, not by any means the end of the story.

First, let’s look at what it says in Miles’s autobiography. Unfortunately that book is unreliable, because it was assembled by poet Quincy Troupe, largely from Troupe’s own interviews with Miles, but also interspersed with excerpts of previously published interviews, and with information from publications about him (I mean, taking a sentence about Miles and rewriting it so that it sounds like Miles said it), notably the books by Jack Chambers, Milestones volumes 1 and 2. None of those sources are indicated. (We can go into the autobiography another time if you subscribers are interested.) So, with caution, I note that the autobiography (p.202) says that his first throat operation was in February or March 1956: “…I had my first throat operation and had to disband the group while I was recovering. I had to have a non-cancerous growth on my larynx removed. It had been bothering me for a while.”

There are a few things that indicate that this passage is not to be trusted:

1. That time period was pretty busy for the Miles quintet with Coltrane, so I can’t see when they would have had time to disband and regroup again.

2. It says the growth was on his larynx. The vocal cords or, as doctors refer to them, vocal folds, are inside the larynx, so this doesn’t sound accurate.

3. This is one of the many passages adapted from the books by Chambers. On p. 231, Chambers writes:

“Soon after the Toronto fiasco, Davis disbanded the quintet for the first time. The main reason was that he had to lay off for a while in order to undergo surgery that would remove a growth on his larynx. It had been bothering him for almost a year, affecting his speech and causing hoarseness.” I think you can see the similarity to Troupe’s wording.

Besides, the two volumes by Chambers were very good for the time they were published (1983 and 1985) but much of the information has since been superseded by more recent research. In fact the itinerary details—when and where Miles performed, when he had surgery, etc.—are the least reliable aspect of the book, for a variety of reasons.

To sum up, let’s discount the possibility that Miles had throat surgery in early 1956.

Later, in November 1956, Miles was on tour in Europe as part of the Birdland All Stars along with Lester Young and others. The tour was produced by Morris Levy, one of the founders of the Birdland nightclub, of whom we’ll say more shortly. British journalist Alun Morgan flew to Paris to hear Miles and noticed his voice problems: “He spoke slowly and with a deep, hoarse voice. A throat ailment had impaired his speech and for the same reason he wore a cravat instead of a tie,” meaning that he wore the cravat to keep his neck warm. (From “Miles Davis: Miles Ahead,” by Alun Morgan in These Jazzmen of Our Times, by Raymond Horricks et al., London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1959. Thank you to Chris DeVito for reminding me about this passage.)

I mentioned in Part One that Miles announced in March 1957 that he was planning to retire from touring at the end of his current engagements, and instead would produce recordings and teach. (John Szwed, in his well-researched Davis biography So What, indicates that the teaching offer had come from Howard University.) These plans never materialized. He finished at the Café Bohemia in Greenwich Village in late April 1957, and that is when he disbanded his group, firing Coltrane and Philly Joe Jones for being unreliable heroin addicts.

He recorded five times with Gil Evans in the month of May, but, true to his promise, he gave no “live” performances. After about six weeks off from gigs, he returned to performing, but only in the New York City area. He was at the Bohemia again from mid-June through mid-August (with a week off for concerts in Central Park) with Sonny Rollins and Art Taylor replacing Coltrane and Jones.

There was a press announcement that Davis would return yet again to the Bohemia for most of September. But he did not return there. The next news of Miles is from the entertainment business publication Variety (Chris DeVito tells me it was the issue of Sept. 11, 1957, p. 62): “Miles Davis is out of circulation for September following major surgery in N.Y.” And then we learn that Davis “is home after surgery and due to play a weekend at the Cork ’n’ Bib in Westbury, L. I. [Long Island], Sept. 27” (DownBeat, Oct. 17, 1957, p. 8; also from DeVito).

The phrase “major surgery” throws us off, but I would suggest that we shouldn’t read too much into it. We don’t know how that phrase got into the news item, whether it was a direct quote from somebody, or inserted by the reporter, or whether in 1957 vocal nodule surgery might indeed have been considered “major.” In any case, we don’t know of any other surgery that Miles underwent in those days, so this could have been a second vocal cord surgery. Certainly, the timing would make sense, since this was also the period when he was thinking about retiring from performing, which was, I’ve proposed, partly due to the damage to his voice.

We don’t know if the Westbury gig happened, but he was apparently back at the Café Bohemia from October 11-16), followed by two weeks at Birdland (October 17-30), and then back to a regular schedule of touring. Apparently he had worked through his personal crisis and felt ready to resume performing. But was that the end of the story about his voice? Apparently not. Years later, Davis collapsed with a bleeding ulcer after a St. Louis concert on March 27, 1975, and the rest of his tour was canceled. He didn’t perform again until April 28, and during that month off, according to Clark Terry, Miles had more nodes removed from his vocal folds. (This is from the late trumpeter Ian Carr’s Miles Davis: The Definitive Biography, p.113.) After a few more concerts, the last being in Central Park on September 5, 1975, Miles stopped performing altogether until June 1981. (I was at his first performance when he returned—more on that another time.)

According to the late Eric Nisenson (‘Round About Midnight: A Portrait of Miles Davis, p.233), Miles’s return was delayed partly because in 1979 or 1980 he had yet another “operation intended to improve his speaking voice (it helped only slightly).” And Miles’s last woman friend, Jo Gelbard, told John Szwed that Miles had one more throat operation not long before he performed at Indigo Blues on December 17-18, 1988. (See Szwed, So What, p.369.) That was three years before he died. So it’s safe to say that Miles continued to struggle with vocal issues until the end of his life.

NOW—the big question: Did Miles ruin his voice by yelling at somebody after surgery?

I believe the original source of this was Nat Hentoff’s book The Jazz Life (1961), in which Miles is quoted as saying that he had frequent arguments with one particular club owner. (To many, this brings to mind Morris Levy of Birdland, a gangster type who also ran Roulette Records and the Birdland tours, among other endeavors. Others have guessed that it was concert promoter Don Friedman—not to be confused with the pianist. But they could be confusing that with the story that Miles knocked out Friedman, which is in the Autobiography p.202.) Miles goes on to say that after the surgery, “I wasn’t supposed to talk for ten days. The second day I was out of the hospital, I ran into him and he tried to convince me to go into a deal that I didn’t want.” Hentoff concludes, “In the course of the debate, to make himself clear, Miles yelled himself into what may be permanent hoarseness.”

This appears to be the source of the version told in the autobiography (p.202):

“After I got out of the hospital, I ran into this guy in the record business who was trying to convince me to do this deal. During the course of the conversation I raised my voice to make a point and fucked up my voice. I wasn't even supposed to talk for at least ten days, and here I was not only talking, but talking loud. After that incident my voice had this whisper that has been with me ever since.”

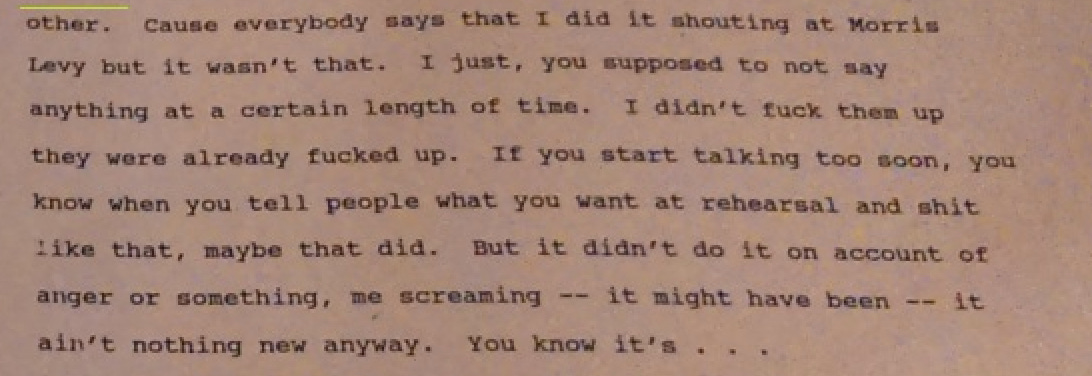

But Miles gave another, complementary explanation to Quincy Troupe. Troupe donated his papers to the Schomburg branch of the New York Public Library, and anybody can make an appointment to look at the unpublished parts of the autobiography (it’s typical for book manuscripts to be shortened before publication), and the transcripts of his interviews with Miles. Masaya Yamaguchi studied these pages at length and discusses them in his book, New Research On Miles Davis and His Circle. (Szwed’s book also contains insights gleaned from the book manuscript.) Thanks to Masaya, I can share with you what Miles actually told Troupe about his voice—take a look at this:

Now please notice a few key points:

--Troupe didn’t use this in the book at all! Instead he used the story from Hentoff about Miles raising his voice.

--Miles says “I didn’t fuck up my voice—it was already fucked up.” We know that is definitely true, based on the evidence I’ve shared with you.

--He absolutely says it wasn’t due to any screaming or anger, and certainly not with Levy.

--And he suggests that sometimes you have to speak fairly loudly to be heard at a rehearsal, and “maybe that did [it].”

--Most important, Miles does not indicate that there was a specific moment when he injured his voice.

Why did Miles change his story? First of all, in his original story to Hentoff, I do not believe that Miles meant that his conversation with the club owner (possibly Levy), caused his hoarseness—we already know that’s not the case. And he knew it too--he was already hoarse before then. It sounds to me that what Miles was talking about was regret. What he was really saying was that he regretted having raised his voice, because maybe his voice would have healed better if he had not spoken loudly.

But as you’ll read below, it is just about impossible that one such incident was the cause of his permanently hoarse voice. And I suspect that, while in 1961 he thought that talking loudly may have ruined his voice for good, he learned from various doctors over the years that one such incident could not have caused his lifetime of vocal issues. And that’s why he gives a different, more nuanced story to Troupe—which Troupe didn’t use. It appears that Quincy preferred the more dramatic—but incorrect—story that he had given to Hentoff about 30 years earlier.

I learned quite a bit more about nodules during conversations (in October 2022) with two physicians:

Mark Courey, M.D. is Professor of Otolaryngology, Director of the Eugen Grabscheid Voice Center and Division Chief of Laryngology in the Mount Sinai Health System in Manhattan. He points out that certain ways of using one’s voice can over a period of time cause changes in the vocal folds, a scarring of sorts, often referred to as nodules. These nodules do not result from one incident of yelling, not even if it’s right after surgery! As Miles himself noted, and as was observed by journalists and audible on recordings, his voice sounded hoarse before the surgeries.

Miles drank and smoked, which are both hard on the vocal folds, but most important, he probably unwittingly used his voice regularly in a way that stressed his vocal folds. (Dr. Courey specified that it’s indeed most likely that Davis had nodules, which develop gradually over time—and not polyps, which are mentioned in some articles. Polyps are softer and thus easier to remove.) Dr. Courey’s approach is, whenever possible, to advise the person to reduce use of the voice and to work with a voice therapist or a speech-language pathologist to improve voice production methods, before attempting surgery. In this he follows in the footsteps of such pioneers as Doctors Eugen Grabschied, Wilbur James Young, Marc Bouchayer, and Robert Ossoff.

Dr. Courey notes that resting the voice is a diagnostic tool, to see how much of the scarred tissue will heal quickly. But, he continues: “That is like a crash diet that does not result in sustained changes. We want sustained changes, so we teach modified voice use. We reduce the volume and overall amount and then re-educate the patient on how to produce the voice efficiently, with less trauma to the vocal folds. If the person continues to use his or her voice in the same way, without re-education, the lesions will certainly return eventually.”

I personally know singers whose vocal fold nodules went away with reduced use and with education as to the proper use of the voice. But changing habits doesn’t work in every case, and clearly it didn’t work in Miles’s case. It’s also possible that Miles did not have access to the kind of voice education that is available today, or didn’t practice it diligently enough to make a dramatic difference.

Dr. Myron Marx, a radiologist who has been associated with the San Francisco Opera in a medical capacity since 1987 and is the current medical advisor to the company, notes that, as with all surgeries, not all vocal fold surgeries are 100% successful. Yes, resting the voice after surgery is important, but even if one follows all of the doctor’s orders to the letter, the voice might not return to exactly what it was before. Even with the best of care, scar tissue can form again on the vocal cords, and that will affect the sound of the voice. He also notes that in rare cases nodules form even when the person’s vocal habits seem fine.

Both doctors emphasized that the cause of the nodule-like changes to begin with was Miles’s unconscious vocal habits, and that unless those habits are corrected, nodules can return, or never go completely away. And, although Miles also said in the Troupe manuscript that he thought it had something to do with playing the trumpet, both doctors felt that playing the trumpet should not affect the vocal cords, since it doesn’t involve one’s voice. The only exception to that, I’d say, would be trumpeters who often use a “growl” sound which they make in their throat—but of course Miles was not a “growl” specialist.

(Here’s one method of how to growl on the trumpet.)

It’s true that after surgery for nodes it’s recommended not to speak at all for a number of days—the exact number depends on the case, as determined by the doctor. But to say that your voice might not heal properly if you spoke is not to say that you’d permanently damage your voice, and certainly not as a result of just one incident.

And, as noted above, the surgical route is not always successful. In a famous example, Julie Andrews had surgery to remove vocal nodes in 1997, and she never recovered her full singing voice. Also, Adele had the surgery in 2011, and she had to cancel the end of her 2021 tour because the problem recurred. Harry Belafonte says in his 2011 memoir My Song (written with Michel Shnayerson) that he had several operations to remove nodules on his vocal cords, none of which fully solved his issue, which is why he’s had a hoarse voice for many years. But I don’t see people ridiculing Belafonte, Julie Andrews and Adele, condemning them for ruining their own voices.

Was it Miles’s fault? No--not in any fair and sensible evaluation of the situation. Do you seriously want to continue blaming him?

And did it bother him? Again, as I said in Part One, very much so! I don’t believe for a minute what it says in Miles’s autobiography: “I used to be self-conscious about it, but eventually I just relaxed and went with it.” (p.202) I wonder if those are even his words. (I haven’t seen them in the manuscript at the Schomburg library.) If he was “relaxed” about it, why did he reportedly have surgery again in 1975, 1979-80, and 1988?

If he was “relaxed” about it, why did journalist and musician Leonard Feather, who hung out with Miles on many occasions, say that his voice is “a source of psychological and physical discomfort, and a subject he prefers to avoid”? (From a 1972 article, reprinted in Feather’s From Satchmo to Miles, p.236.)

Szwed notes, perceptively (p.126-7): “If he had been shy about speaking publicly before, his self-consciousness about his voice now made him more so, and he spoke less and less. When he did speak, he often was not heard and had to whistle to get attention.”

Miles himself told Cheryl McCall, in Musician magazine, March 1982, “they think that my voice every time I’m straining to talk sounds like I’m drunk or high or something…When I get on the phone they say, ‘Yes ma’am, what did you say?’ They think I’m a woman.” (laughs)

Just because he could laugh about it doesn’t mean he was okay with it. However, during the 80s, at the height of his fame, he was interviewed for the first time on a number of television shows—Dick Cavett, 60 Minutes, and more. Clearly, although he wasn’t happy about his voice, he realized that by then people knew about his voice, and he wouldn’t need to explain it. It had become a trademark of sorts. I wouldn’t say that he “relaxed and went with it,” but he had learned to live with it.

It’s totally unfair of people to blame Miles for his own vocal problems. But it’s typical of the negative attitude that so many have about Miles—for reasons that only they understand.

In Part Three we will listen to audio excerpts of Miles’s voice through the years. I already shared with you the earliest one, from 1947, at the end of my post on Miles and his musicians—but I’ll repeat that one. In the meantime, I have lots of other things to share with you from my files!

lewis great article !! thank you so much

best

richie beirach

Congratulations for this extraordinary article. Without a doubt, your wisdom makes us lovers of modern jazz know its history a little more every day. The life and work of Miles Davis is certainly worthy of study and we will never know everything about him.