As you know, once in a while I offer a guest post. Today’s essay was written by subscriber and Monk researcher Jerry Suls. He has looked into some of Monk’s song titles, and has come up with some very creative connections that, I think you’ll agree, help to make sense of these mysterious names. The footnotes refer to the numbered reference sources at the bottom. (Below that is a leadsheet of “Brilliant Corners” as a bonus for Paying Subscribers.)

Notes on the Titles of Thelonious Monk's Compositions

By Jerry Suls

This essay aims to shed more light on the origins of the titles that Thelonious chose for his compositions. Robin Kelley, Chris Sheridan, and Orrin Keepnews’ son Peter have already researched the origins of many of Monk's titles. [1,2,3, 4] I will not duplicate their efforts here. However, additional observations and information about Monk's history, and interviews with friends, acquaintances, and band members, may provide further insights or leads for future research about some Monk titles.

Songs with "Monk" in the title

Monk is not the first jazz composer to insert his or her name in a title. John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie created a few compositions that featured his name, such as "Dizzy Atmosphere" and "Birks' Works.” There are many composition titles that featured references to Charlie "Bird" Parker. One must be cautious about interpreting titles, because record producers or other musicians often named pieces that the musicians left untitled. [5] But Monk’s titles appear to be his own, and he probably set the upper range for featuring his own name. Of his 70-plus compositions, there are "Monk’s Dream," "Blue Monk," "Monk's Mood," "Thelonious," "Monk's Point," and "Blue Sphere.” (In his teens, Monk adopted "Sphere" as his middle name, after his maternal grandfather's first name). [2]

It seems to me that he wanted to put a stamp on his music. Perhaps the strongest example is his composition "Thelonious," which was recorded in October 1947 at his first session as a leader. This might seem like a presumptuous gesture. At that time, Monk was mainly known by bebop insiders. But Monk could be reasonably assured that his unusual name would draw attention, just as the eccentric hats, sunglasses with bamboo frames, etc., that he wore. Besides highlighting himself, Monk, no doubt, was signaling that he and his music were special and important: Monk is his music and his music is Monk.

Bud Powell and "In Walked Bud"

“In Walked Bud,” named for pianist Bud Powell, might signify more than his well-known affection for his younger friend and protégé. The composition, built on the harmonic changes of Irving Berlin’s standard “Blue Skies,” may be a playful Monkish commentary. Bud, who lived in Monk's neighborhood, was a classically trained prodigy who became entranced by jazz in his early teens and was initially attracted to the stride masters, such as James P. Johnson, and Fats Waller (as was Monk). Around 1942, Monk took the 17 year-old Powell under his wing, recognizing that he possessed the technique to play Monk's demanding compositions, and had something of his own to contribute. Soon, Monk introduced Bud around to established musicians and encouraged them to let Bud sit in on the bandstand.

By calling the tune “In Walked Bud,” Monk seems to be signaling the arrival of a new and unique talent. Monk biographer Thomas Fitterling noted about the first recording of “In Walked Bud,” "With a descending whole tone run con brio, he dramatizes his friend Powell 'walking in.’" [6] Indeed, by the mid to late 1940s, Bud Powell was considered a master of bebop⎯Charlie Parker’s closest counterpart on the piano.

“In Walked Bud” also evokes an association with “Lester Leaps In,” a composition tenor saxophonist Lester Young recorded with a Count Basie small group. (Pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines’ “Father Steps In” might also have been an inspiration.) “In Walked Bud,” and its “Blue Skies” origin, also may reflect the affection that Monk had for Bud. Consider this excerpt from the “Blue Skies” lyrics: “Bluebirds singing a song. Nothing but bluebirds all day long. Never saw the sun shining so bright. Never saw things going so right.” [7] In Monk’s reclusive moods of the 1960s, Bud was one of the few people reported to energize him, when they crossed paths. (Bud died in 1966, Monk in 1982.) [8]

Worry Later/San Francisco Holiday

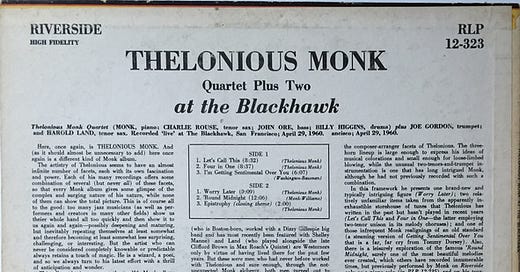

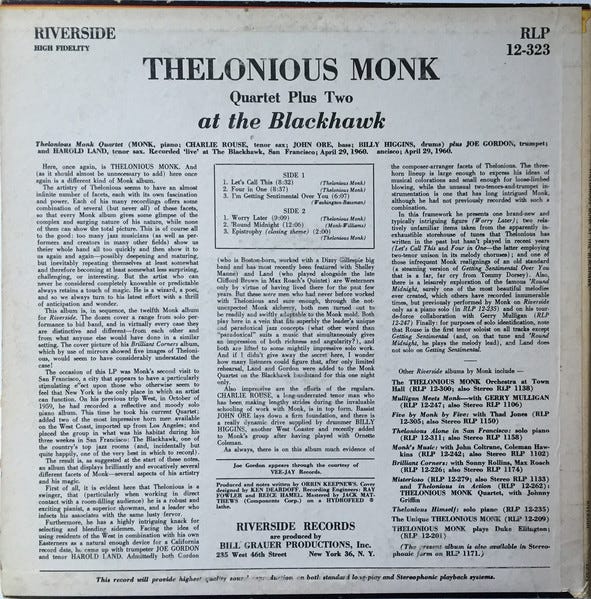

Producer Orrin Keepnews recalled that “During rehearsal earlier in the week, I had asked the composer if he wanted to name his new tune now, or worry about it later. “Worry later”was the response—and that, I decided, was an ideal title.” [9] In fact, that was the title on the original album:

But Monk later changed the composition's title to "San Francisco Holiday," after an especially enjoyable West Coast trip that he took with his family in April 1960. The piece was first recorded in the studio and at the Blackhawk nightclub , for the album shown above, during that trip.

Pianist and composer Joel Forrester, a close friend of the Baroness Nica, proposed that she probably had a hand in the renaming. He observed that Monk wouldn't have naturally used the British-ism "holiday" (as the British say, “We were on holiday”), but Nica would have said that. [10] [Lew adds: “Vacation” would be more common among Americans.]

Gallop's Gallop

This composition, “Gallop’s Gallop,” sounds like it might be dedicated to someone, but no one named “Gallop” who was in Monk’s circle has emerged. The piece was written expressly for a 1955 recording session led by his younger friend, alto saxophonist Gigi Gryce. I inquired with Noal Cohen and Michael Fitzgerald, biographers of Gryce, but they reported no record of Gigi having “Gallop” as a nickname. [11,12] However, a clue to the title may lie in the fact that a gallop is a type of walk, a fast stride. As mentioned earlier, Monk was attracted to the stride pianists, including James P. Johnson (whom he knew and who lived in his neighborhood) and Fats Waller. "Gallop’s Gallop" may represent Monk's word-play on "stride." The melodic-rhythmic line has a lop-sided quality and almost turns on itself until it reaches resolution. It is rarely performed because, although the harmonic changes are straightforward, the rhythmic/melodic line is difficult to navigate.

52nd Street Theme

In the 1940s and 1950s, Monk's lack of exposure, and the idiosyncrasies and challenges of his compositions, discouraged their performance by other jazz musicians. But "52nd Street Theme" was an exception because it was a piece adopted by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie as a closing number for their sets at nightclubs. West Fifty-second Street in New York City, between 6th and 8th Avenues, was the neighborhood where many jazz clubs thrived from the early 1930s into the 1950s. In the early 1940s, bebop was at first heard almost entirely in Harlem venues, but West 52nd Street represented its wider exposure in Midtown Manhattan.

Curiously, Monk never recorded "52nd Street Theme,”** and rarely (if ever) performed it. [4] This seems unusual, but there may be two explanations. First, Monk did not give his own composition play because it was not known by his preferred (and original title), which was “Nameless.” (In fact, Monk obtained a copyright under this title in 1944.) [2] Later Monk said he actually preferred “Bip Bop” as the title [2]. He told an interviewer, “I was calling it bipbop (sic), but the others must have heard me wrong.” [13] There is no record regarding why Monk preferred “Bip-bop.”

The title, "52nd Street Theme" was suggested to Dizzy Gillespie by the jazz promoter, composer and critic, Leonard Feather⎯who was an early bebop supporter, but not an early advocate for Monk. In fact, Feather wrote a very critical review about one of Monk's early recordings. In addition, Monk’s son has reported that his father was very angry about Feather minimizing Monk's role in the birth of bebop in his book, Inside Bebop (reprinted as Inside Jazz). [14, 15, 16]

The popularity of "52nd Street" among beboppers may have been bittersweet for Monk during the mid-1940s and early 1950s, when Parker and Gillespie received considerable press attention and attracted music gigs, while Monk received little favorable press coverage and was struggling economically. Some of Monk’s problems with getting work, admittedly, were self-imposed: he did not like to be away from home, which restricted his touring, and he liked to perform on his own terms. Furthermore, in 1951 he was arrested and convicted on narcotics charges (read the details in Lewis’s essay here), which caused him to lose the cabaret card that was required to perform in New York City nightclubs. His card was not reinstated until 1957. [2,3]

In short, ”52nd Street" may have elicited negative associations for Monk, and that may be why he never recorded it. Also, Monk was known to be critical of bebop becoming too formulaic in the hands of the second generation of players. [17] Monk also was insistent that his music was not bebop. Although he contributed important harmonic elements to it, he took a different melodic and rhythmic approach in his composing and performing.

Introspection

“Introspection” has an "edgy" melodic and rhythmic flavor with a theme that seems to turn back on itself. (On the original 1947 recording, the theme starts when the drums enter at 0:22.) Fitterling writes, "...if you try to hum it, you soon discover how unconventional it is." [6] At its first recording, Monk created a feeling of disorientation by having the bass player use a 2-feel during the A and C sections while the drummer provides a 4-feel throughout the piece. Eric Nemeyer observes that the piece has “seemingly (but not really) out of balance phrasing." [18] The other disorienting element is that "Introspection" does not follow the usual convention of the AABA form, where the key is spelled out in the A section; instead, the key is only revealed in the B section.

But why call this disorienting piece, "Introspection"? Was this Monk's musical representation of self-reflection? Monk was known to sit at the piano for many hours a day at home, working and re-working compositions and improvisations with intense concentration. Teddy Hill, the manager of Minton’s Playhouse, told an interviewer that Monk would come to use the piano when the club was closed in the afternoons, or very late at night after all the other players had left, and could be “so absorbed in his music he appears to have lost touch with everything else." [19] Perhaps Monk's choosing "Introspection" as a title represents his concentration when he was composing. The "off-balance" sensation elicited by the piece may simulate a disorientation caused by concentrating too intensely.

[Lewis adds: We should note that Ralph Burns recorded an original piece called “Introspection” in 1946, but it was recorded in Los Angeles and not released until 1949, so Monk would not have known it. It’s a kind of early “third stream” ballad with no similarity to Monk’s piece.}

Evidence

“Evidence” employs few notes but with exaggerated rhythmic displacement. The title riffs on the popular song “Just You, Just Me,” which provides the basic chords on which "Evidence" was created. Some writers claim the title evolved from 'just you and me" translated to “just us,” which, spoken without a break, sounds like “justice.” [2,3] There is no record of Monk ever saying this, but in fact, he called this piece “Justice” before he settled on “Evidence.” What figures in the deliberation of justice? One answer is, indeed, evidence.

The title's origin may deserve elaboration, however, because “evidence” is only one of several possible associations with "justice." I propose that the origin of Monk's title may lie in events of the fourth week of June 1948, which preceded the first recording of “Evidence.” After ending his last set at the Royal Roost nightclub, and about to leave, the police stopped Monk and searched him. A small package of marijuana (the evidence) was found on his person, leading to Monk being arrested and held in jail overnight. With some difficulty, his family managed to pay the bail, so that he could be released awaiting a trial date.

Only three days after the arrest (July 2, 1948), Thelonious and his band were in the studio to record again for Blue Note records. "Evidence" was one of the new pieces. There is some indication that Monk had been working on it for some time. Robin Kelley claims that one can hear flashes of what became "Evidence" in Monk's comping behind Dizzy Gillespie's solo on "Groovin' High" from a recording of Dizzy's big band in June of 1946. [2, p. 114)

It seems more than coincidence that Monk settled on the title "Evidence" within days of being arrested for marijuana possession. Its melody line, like the original one for “Just You, Just Me,” is quite simple, and like “Misterioso," which was recorded on the same day, it has a minimalist flavor. However, because of the way Monk places the notes rhythmically, it has both a 4/4 and 3/4 feel. As a result, it can be challenging to play. Also, it presents a parody of the simple melody and rhythmic structure of the popular tune, and it has the flavor of a detective or mystery film, perhaps another association with evidence and justice.

The detective or mystery flavor is reinforced by aspects of its first recording. Despite it being a new composition at the session, Monk presents it in an unusual way. He begins with an 8-bar introduction that refers to the opening A section of the piece, followed by Milt Jackson improvising on vibraphone. A full rendering of the AABA theme doesn’t occur until the end of the recording. Martin Williams observed that the performance benefits from knowing the theme after the fact. [20, p. 155] In this sense, the entire performance is something of a mystery—the theme is not fully resolved until the end, like a mystery story.

[Lew adds: A very clear rendering of the theme can be heard on Steve Lacy’s brilliant 1961 performance with Don Cherry.]

Functional

“Functional,” a blues on solo piano, may be one of Monk's broad puns. The blues has proven to be a useful and adaptive—that is, functional— musical form for conveying a range of emotions from melancholy, tragedy, longing, joy, and humor. However, Monk might also be riffing on the term, “funky,” and referring to the 1950s style associated with heavily blues-gospel flavored hard bop, as played by Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers or the Horace Silver Quintet. Robin Kelley reports that the title was probably made up on the spot in the studio at the 1957 recording date. [2]

Criss-Cross

The title of "Criss-Cross" is a structural reference. Melodic fragments from the A section reappear (transposed to another key) in the B section, and fragments from the B section appear in the A section. So the parts effectively criss-cross. It may not be coincidental that the original title, “Sailor Cap,” refers to a hat constructed by folding and creasing fabric or paper in several steps, length-wise, width-wise, and then creating flaps that overlap. As a “sidebar," a popular film noir entitled “Criss Cross” was released in February 1949. [21] The film featured several “double crosses,” and triple and quadruple “crosses,” among the characters. Monk was known to go the movies frequently, so the film may have been an indirect inspiration when Monk recorded his piece in July, 1951.

[Lew adds: The tune is written “Crisscross” on the copyright registration. Still, the film could have been an inspiration. It has two nightclub scenes featuring Latin flutist Esy Morales and his band. In another scene, the lead actress sits at a piano and plays “I’ll Remember April.” So the musical choices in the film were also probably of interest to Monk, as well as the plot.]

Straight, No Chaser

The blues, ”Straight, No Chaser,” was first recorded at the same 1951 session as “Criss-Cross.” (Lew notes: The original 78 rpm label had no comma, but the copyright does have it.) The title might seem like a clever off-the-cuff invention, riffing off of a colloquial request for liquor without a beer “chaser” afterward to cut the stiff taste. In other words, one asks for “straight” liquor with no dilution of the effect of the alcohol (and no ice either). However, the title Monk chose may refer playfully to the piece’s structure. Unlike many blues that present two or three motifs commonly in four-bar units, “Straight, No Chaser” uses a single motif that is elaborated and restructured and sounds like a single line over a changing harmonic framework. In other words, one idea is played again and again, each time in a different part of the measure and with a different ending. It provides a continuous line (although with variation) with no “dilution.” New players often make errors because learning the appropriate timing requires complete concentration.

Ugly Beauty

In 1967, a year before Monk left Columbia Records, he composed a piece that he called "Ugly Beauty.” This song, his only waltz composition, moves from stark dissonance to lovely consonance. Adam Shatz speculates that the title is "...Monk's translation of jolie laide, a French expression for a woman whose less pleasing features somehow make her more attractive.” [22] The idea that beauty might arise out of asymmetry, out of irregularities, imperfections, and apparent flaws, would certainly have appealed to Monk.

[Lew adds: He did record another waltz, but it wasn’t his song. It was his arrangement of “Carolina Moon,” which retained the 3/4 meter of the original, but in double-time.)

Brilliant Corners

“Brilliant Corners” is the last title to be considered here and it led me down several unproductive paths. "Brilliant Corners" consists of twenty-two bars, arranged A (eight bars), B (seven bars), and repeat A (seven bars), with unexpected accents. The initial section of 8 bars (rather than two times eight, for 16) is unusual as are the other sections with an odd number of bars. Does the title reflect the musical architecture, or a physical location? We know that Monk loved walking around Manhattan. Where were the “brilliant” corners? Times Square, sometimes referred to as the "Center of the Universe," and known for its neon signs advertising products and Broadway theaters is one candidate. However, in October 1956 when Monk recorded this composition, Times Square was beginning to lose its glamor and appeal. Another scene of brilliant corners in Manhattan is the nexus of Broadway and Fifth Avenues, near 23rd Street, where the triangular 22-story Flatiron Building is located.

In jazz of the late 1940s and 50s, the most conspicuous “corner” in the New York City jazz world was Birdland, the famous jazz club⎯named after Charlie Parker⎯ and dubbed “The Jazz Corner of the World” by its owners. [23] The original Birdland was opened in December 1949 and located at 1678 Broadway, just off the corner of West 52nd Street. The actual room was below street level and could accommodate an audience of 500, with a stage large enough for big bands to perform. However, Parker did not perform there frequently because he was unsatisfied with the pay the owners were willing to offer. Monk did perform there when it first opened, but the club's original manager stopped scheduling him because he placed his drink glass on the new piano, despite the manager's repeated complaints. [2, p. 501]

Neither the place origin nor Birdland origin seem very plausible. Something about the piece's structure may provide a resolution. One potential clue comes from Terry Adams, the keyboardist for the band NRBQ, who happened to see Monk’s original manuscript for "Brilliant Corners." [24] In the top right corner of the page “Brilliant” was written horizontally; “Corners” was written vertically going down.”

[Lewis adds: I haven’t seen that manuscript, but I do have a more conventional one that was created by a copyist when this piece was copyrighted in 1962. It’s below for Paying Subscribers.)

The tune begins with “Da-deeda-Dah,” which resembles the start of a symphony, and after the first chorus, the same theme is played again but twice as fast—later to return to the slower tempo for the next soloist. Both sections build to the repetition of one note, like a traffic horn, followed by an ending phrase. Perhaps Monk wanted the musicians to pause at the ending phrase on the first pass and abruptly move ("turn the corner”) to the next section. The sections of a conventional jazz tune usually consist of even numbers of bars, such as 8 or 12. "Brilliant Corners" requires ending abruptly at the end of the 7th bar, even while improvising. Its ABA form is a relative rarity in jazz compositions, as is the odd number of measures in the B section and in the repeat of the A. Combined with the slow-fast-slow tempos, the unusual bar lengths explain why the piece was challenging. The musicians tried to play “Brilliant Corners” to Monk's satisfaction around 25 times. [Lew notes: It’s fair to assume that most or all of these takes broke down at some point, and were incomplete.] Finally, the record producer Orrin Keepnews spliced together some parts to get a useable rendition. [9]

Guitarist Richard "Duck" Baker and the late trombonist Roswell Rudd, who were very conversant with Monk's music, had no special information. However, when I inquired with Joel Forrester, co-leader of the Microscopic Septet, and close friend of the Baroness “Pannonica,” he wrote, "I've no idea about ‘Brilliant Corners,’ except that it reduces to [has the same meaning as] Sharp Turns, which is just what happens⎯in both the heads and the solos⎯halfway through the form: the time doubles up." [25]

Forrester's explanation seems to me to be the most straightforward, although without additional information, “Brilliant Corners” remains a puzzle, which may have been intentional on Monk's part. However, despite the mystery, "Brilliant Corners" was adopted as the name of a national journal devoted to jazz-related literature. Sponsored by Lycoming College in Pennsylvania since 1996, the journal continues to publish poetry, fiction and non-fiction by distinguished writers and critics. [26]

When Monk Lacked a Title

There are occasions at recording sessions when Monk was asked for a title by the recording producer, but he had not settled on one. I already recounted that “San Francisco Holiday” was originally Monk’s response, “Worry Later.” Peter Keepnews proposes the titles “Let’s Call This” and “Think of One” as other such instances, perhaps in response to the questions “What do we call this?” and “What’s the title of the next one?” [1,p.19]. (“Think of One” may also have seemed fitting to Monk because the theme was based on a one-note theme with unisons and major seconds.) “Who Knows” may also fall into this category.

Conclusion

The preceding notes offer additional information gleaned from the still growing literature about Monk, from interviews and informal inquiries of musicians and other experts, and from cautious (hopefully) speculation. No doubt, as long as Monk's music attracts and intrigues listeners and musicians, so will his unusual titles.

References

{1} Peter Keepnews, Liner Notes for Thelonious Monk, The Complete Prestige Recordings. Fantasy Records, 3PRCD-4428-1. 2000.

[2] Kelley, Robin D.G. Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

[3] Sheridan, Chris. Brilliant Corners: A Bio-discography of Thelonious Monk. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001.

[4}. http://www.monkzone.com/compositionshtml.htm Accessed November 8, 2023.

[5] Reig, Teddy with Edward Berger. Reminiscing in Tempo: The Life and Times of a Jazz Hustler. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press & the Institute for Jazz Studies, Rutgers University, 1990.

[6] Fitterling, Thomas. Thelonious Monk: His Life and Music. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Hills Books, 1997.

[7] Berlin, Irving Blue Skies lyrics © Songtrust Ave, Warner Chappell Music, Inc

[8] Alan Groves and Alyn Shipton, The Glass Enclosure: The Life of Bud Powell. (New York: Continuum, 2001.

[9] Orrin Keepnews, The View from Within: Jazz Writings 1948-1987. (New York: Oxford University Press,1987), p. 144.

[10] e-mail communication from Joel Forrester to the author, January 28, 2024.

[10] Noal Cohen & Michael Fitzgerald, Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce. (Berkeley CA: Berkeley Hills Books, 2002).

[11] E-mail communication from Michael Fitzgerald to the author, October 2012.

[12] Barry Farrell, “The Loneliest Monk,” Time, February 28, 1964, pp. 84-88. Reprinted in Rob van der Bliek (ed.) The Thelonious Monk Reader, (New York, Oxford University Press, 2001), 155.

[14] Leslie Gourse, Straight No Chase: The Life and Genius of Thelonious Monk (paperback edition). New York: Schirmer, 1998), 38.

[15] Leonard Feather, The Jazz Years: Earwitness to an Era. (New York: Da Capo Press, 1987), 105.

[16] Leonard Feather, Inside Bebop. (New York: J.J. Robbins, 1949). Republished as Inside Jazz.

[17] George T. Simon, “Bop’s Dixie to Bop”, Metronome, April 1948, 20, 34-35.

[18] Eric Nemeyer, “Introspection, Composed by Thelonious Monk,” Jazz Improv, Winter, 199

[19] Ira Peck, “The Man Who Dug Bebop,” PM, February 22, 1948. Also Robert Kotlowitz,"Monk Talk," Harper's Magazine, September 1961, 23.

[20] Martin Williams, The Jazz Tradition (2nd revised edition). New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

[21] Criss Cross (1949), directed by Robert Siodmak. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criss_Cross_(film)

[22] Adam Shatz, 2017. "Blues to Come." March 17, 2017, Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.theparisreview.org.blog/2017/03/27/blues-to-come/

[23] Leo T. Sullivan 2023, Birdland the Jazz Corner of the World: An illustrated tribute, 1949-1965. Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA

[24] Terry Adams, May 28, 2017, e-mail to the author.

[25] e-mail communication from Joel Forrester, Tue, Aug 1, 2023

[26] Brilliant Corners: A Journal of Jazz and Literature. https://www.lycoming.edu/brilliant-corners/. Website accessed January 23, 2024.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to many musicians, listeners, and music researchers for the information and insights they provided. The list includes Roswell Rudd, Duck Baker, Terry Adams, Joel Forrester, Michael Fitzgerald and Lewis Porter.

[THANK YOU JERRY for these fascinating thoughts on Monk! I would like to add my own thanks to Don Sickler, jazz musician and publisher, and to Morgan Davis at the Library of Congress Music Division. Paying Subscribers, scroll down for a leadsheet to “Brilliant Corners.”

All the best,

Lewis]

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.