(Paying Subscribers, at the bottom you’ll find pages from a Black newspaper that include a Tatum profile, with a portrait by artist Calvin Bailey, plus news of Ella, Basie, Blanton, Paul Robeson, and more.)

This is the last of three essays presenting newly discovered, never-heard recordings. With items like these, there is often not much known about them, so I’ve already had to do a tremendous amount of research in preparing the previous essays. This last track presented a special problem: On this track only, a trombonist appears who is not identified on the handwritten labels, and who isn’t in the home movies (from which we saw stills before).

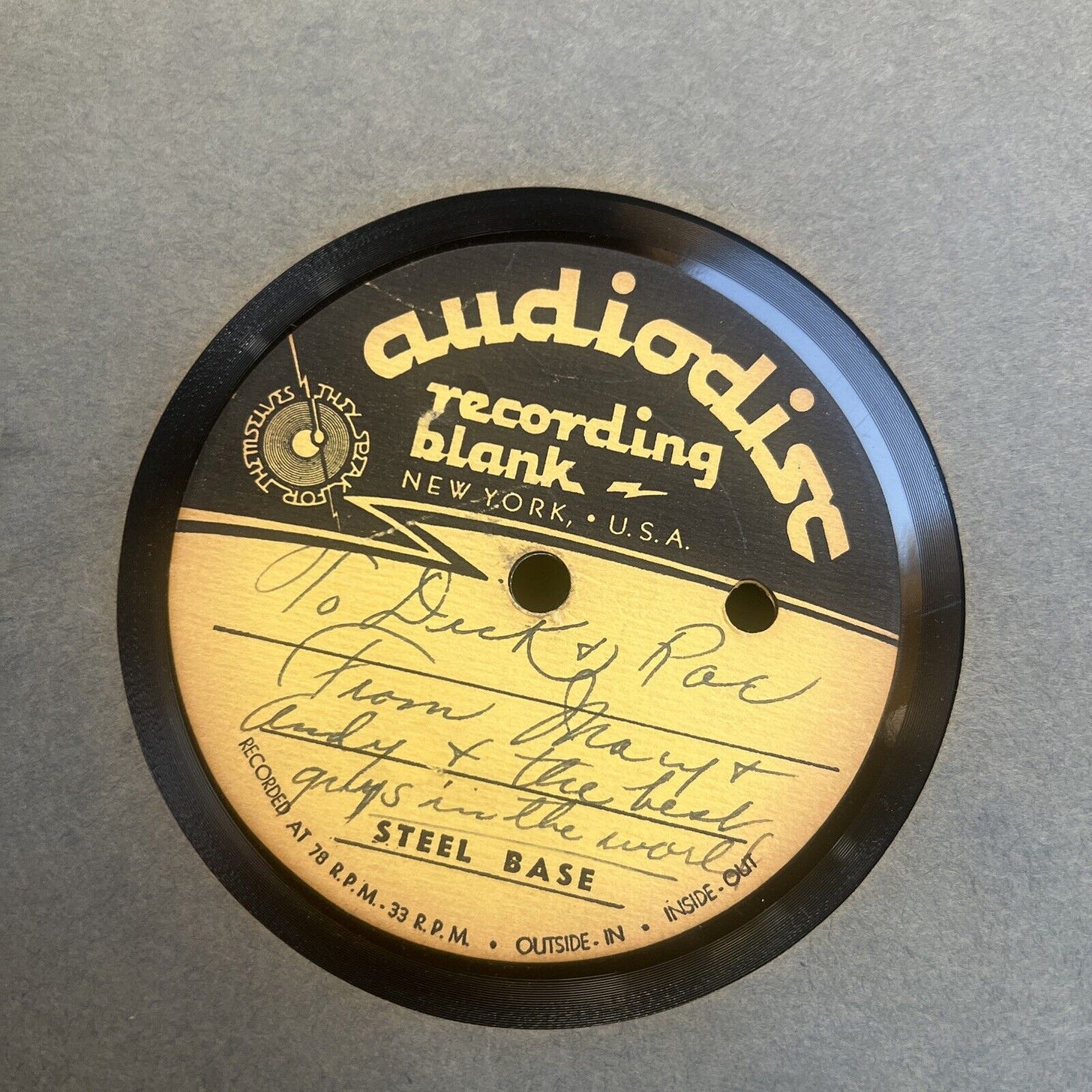

Unlike the other disc, where the musicians’ names are written, this one, evidently intended as a gift to friends of the hosts Andy and Mary Mackay, simply says “Dig this!” on the side that we heard last time. And on the side we’ll hear today it says: "To Dick + Rae from Mary + Andy + the best guys in the world.” (It’s not known who Dick and Rae are.):

Let’s listen to the recording, and then we’ll go through the process of finding the mystery trombonist. This last track is a jam session based on the chords of “I Got Rhythm,” complete with the two-bar tag that stretches the chorus to 34 measures, as in Gershwin’s original. You will hear Art Tatum at the piano and Slam Stewart on bass. First, they accompany Eddie Barefield’s fine solo on alto saxophone. Then Tatum solos with great drive, and he goes “out” briefly at 1:40. Next, at 2:23, we hear from the mystery trombonist, while Art provides a solid “stride” backing, and Slam slaps the bass. Slam solos next while singing along, as always. From about 4:00 to 4:10, Tatum plays some very sophisticated chords behind him. Then he resumes his stride style for Slam’s second chorus, but he goes “out” again at 4:35.

Tatum then takes another solo chorus, but there’s a slight skip in the disc at 4:54, so try to not let it disturb you. At the bridge, which starts at 5:02, he plays some wildly complicated rhythms going right into the last A section, but if you manage to count steadily through it, you will find that he is totally in control. (You will often read about Tatum or Earl Hines, one of his influences, “getting lost,” but I think it’s only the listener who gets lost.) Finally, Eddie Barefield joins on tenor sax for the last two bars. Maybe he saw that the needle was coming to the end of the disc? Anyway, there’s a lot of great music here. Take a listen!:

GREAT stuff! Now—how shall we go about identifying the trombonist? In brief, there are two main parts to that type of research: First, Step One is to try to identify the artist by sound alone. If one is able to make a fairly positive identification, one goes on to Step Two, which is to document that the artist in question was at that location on that date. In this case we have the exact date, May 30, 1942. To be fair, the date was written on the other disc, but it seems reasonable to assume that this one, with some of the same musicians recorded at the same house, would be from the same date. When the date isn’t known, one can usually provide an approximate date, based on style, audio quality, repertoire, the other musicians on the recording, and so on. As noted in my essay on reference sources, newspapers—especially Black newspapers—are an essential resource for tracing the movements of musicians. Reading through Downbeat and other magazines is important, but it’s definitely not enough.

So let’s start with Step One, the sound: The method is to compare the sound and style of the unknown musician with those of known musicians. That can only be done by someone who is already familiar with most of the well-known musicians of the era in question. One draws on one’s mental database of styles. Sometimes, if one is lucky, the mystery player is a perfect match for a known style. More often, it sounds very much like someone, but not enough to be certain. In that case, one goes to recordings by the artist in question and compares them carefully with the unknown artist. Finally, it’s always possible that the mystery player is truly unknown. After all, not everyone became famous, and made recordings, and so on. In that case one probably wouldn’t be able to identify him or her.

The most unusual feature of this trombone solo is the sliding and slipping all the way up to very high notes. Only a few trombonists played that high in those days. I thought first of Dicky Wells, one of my all-time favorites. Here is a short excerpt from “Six Cats and a Prince,” from a session with Count Basie and Lester Young, March 1944. Dicky alternates squeaky high notes with low notes for, to me, a terrific effect:

It doesn’t exactly match the sound of the unknown player, but it was close enough to make me go on to Step Two, which is: Was Wells in Los Angeles on Saturday May 30, 1942? Wells was with Count Basie at that time, and indeed for most of the period from 1938 to 1950. So guitarist and historian Nick Rossi searched the newspapers, and found that the band was in Birmingham, Alabama on that date. Here is an article and ad from the Birmingham Post of May 30, 1942 that say that the band is playing “tonight.” This was a newspaper by and for whites, so the article notes that Basie will appear before “white patrons”—a segregated theater—and there is a little caricature of a Black person in the ad. These are sad and angering reminders of the Southern past:

It’s slightly possible that Wells could have been somewhere apart from the band. So I kept him in mind, but I moved on, because most likely it was not Dicky Wells.

Then Nick Rossi mentioned Britt Woodman, who was actually from Los Angeles and working there with Les Hite’s group. Later he toured with Ellington, who featured him on “Theme for Trambean,” which ended with Britt playing very low and then very high notes. (This version is from Hamilton, Ontario, February 8, 1954.):

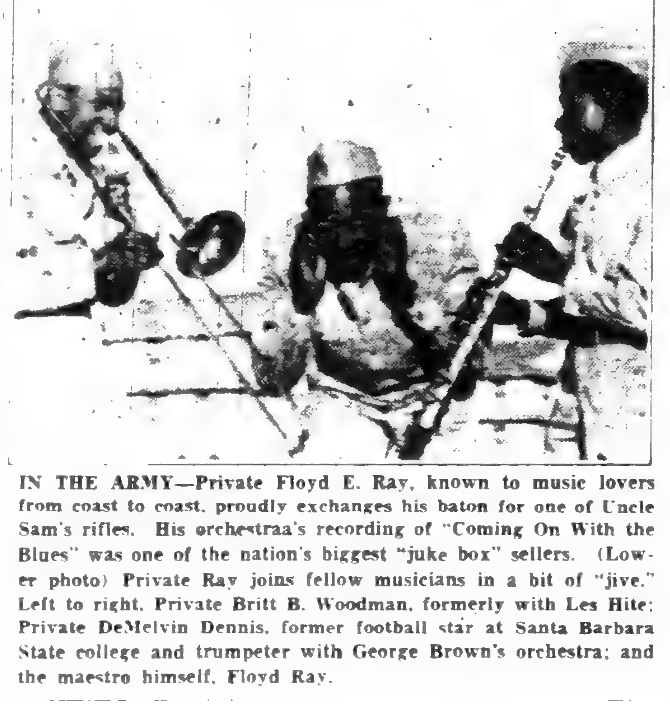

But when we went to the next step, Nick learned from the military records at Ancestry.com that Woodman had registered for the draft in July 1941, and had actually been drafted on April 11, 1942. And I found an item in the California Eagle on June 4 that confirms that he was in the Army, as well as this one from June 11, with a photo of Woodman in uniform:

So, unless he was stationed near L.A. (these sources don’t say where he was), and was on leave on and around our recording date, Woodman was not our trombonist.

Then it hit me—what about Trummy Young? The style reminded me of him, but I didn’t recall him playing that high. I emailed the audio file to my friend and former grad student Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum. Ricky is of course known as an Armstrong expert, but he’s extremely knowledgeable about pre-bop jazz in general. First, Ricky pointed out that on occasion in the 1940s, Trummy did indeed play that high. He pointed me to the end of Young’s solo on the Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP) performance, “Bell Boy Blues,” from 1947 in Pittsburgh:

And Ricky recognized that the mystery trombonist uses one of Trummy’s “pet phrases.” Everyone has favorite phrases, both in speaking and in music. This one is the beginning of “(The Ballad of) Casey Jones,” which has been well known since the early 1900s. Here is the original song performed by Burl Ives in 1947, then the mystery player in 1942, and then Trummy Young playing it with Louis Armstrong in 1953:

(Slam wittily echoes this phrase at the start of his bass solo.)

And finally, I played it for the fabulous trombonist Conrad Herwig, who, you might not know, is a protége´of Trummy’s. He said without a doubt, it is Trummy!

OK, so now that we know it’s Trummy, let’s go on to Step Two and see if he was in L.A. on that day. (If not, we would have to reconsider the dating.) From 1937 through 1943, Young was with the Jimmie Lunceford band, so I searched magazines and newspapers to see where the band performed. I decided to start in March 1942 and work my way up to May 30. One of the first items I saw was this, in Downbeat, March 15, 1942 (by one of their few women reporters):

A similar notice appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier, a major Black newspaper, on March 28, 1942. That one specified that Young was asking for more pay. There was a history of Lunceford’s musicians protesting low pay, while Lunceford himself became wealthy.

Uh oh—this means that Young had left Lunceford before May 30, 1942! But I kept looking, because I knew from the discography that Trummy made records and radio broadcasts with the band later in 1942 and into 1943. So when did he come back? I then found this in the California Eagle, April 16, 1942:

So, Trummy was only out for a few weeks. Lunceford must have offered him a raise, and he returned. To make the rest of this story short, the Black newspaper California Eagle confirmed that the band arrived in Los Angeles on Thursday May 28, with engagements on Friday the 29th and Sunday the 31st, and beyond, but nothing scheduled for Saturday May 30! So Trummy was free to attend the jam session at Mary and Andy Mackay’s place on that day.

In short, I have no doubt that Trummy Young is the “mystery trombonist.”

I hope you have enjoyed exploring these new discoveries with me! I’ll see you again soon!

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Special thanks to Steven Lasker, Mark Cantor, and Nick Rossi for help with this essay.

P.P.S. Paying Subscribers, at the bottom you’ll find two pages from a Black newspaper with news about Tatum, Ella Fitzgerald, Slim and Slam, Paul Robeson, and more.

P.P.P.S. To inquire about professional use of the home movies mentioned, contact jazz film expert Mark Cantor, whose collection is one of the world’s largest, at: markcantor@aol.com

You are also encouraged to visit his site, where he posts rare clips and film research.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.