(Paying Subscribers, your two gifts are at the very bottom.)

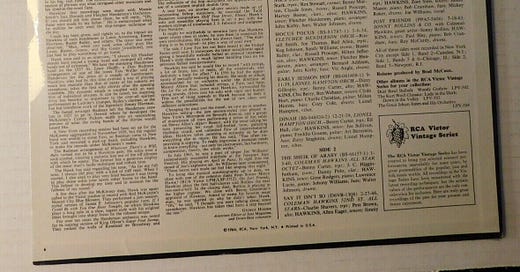

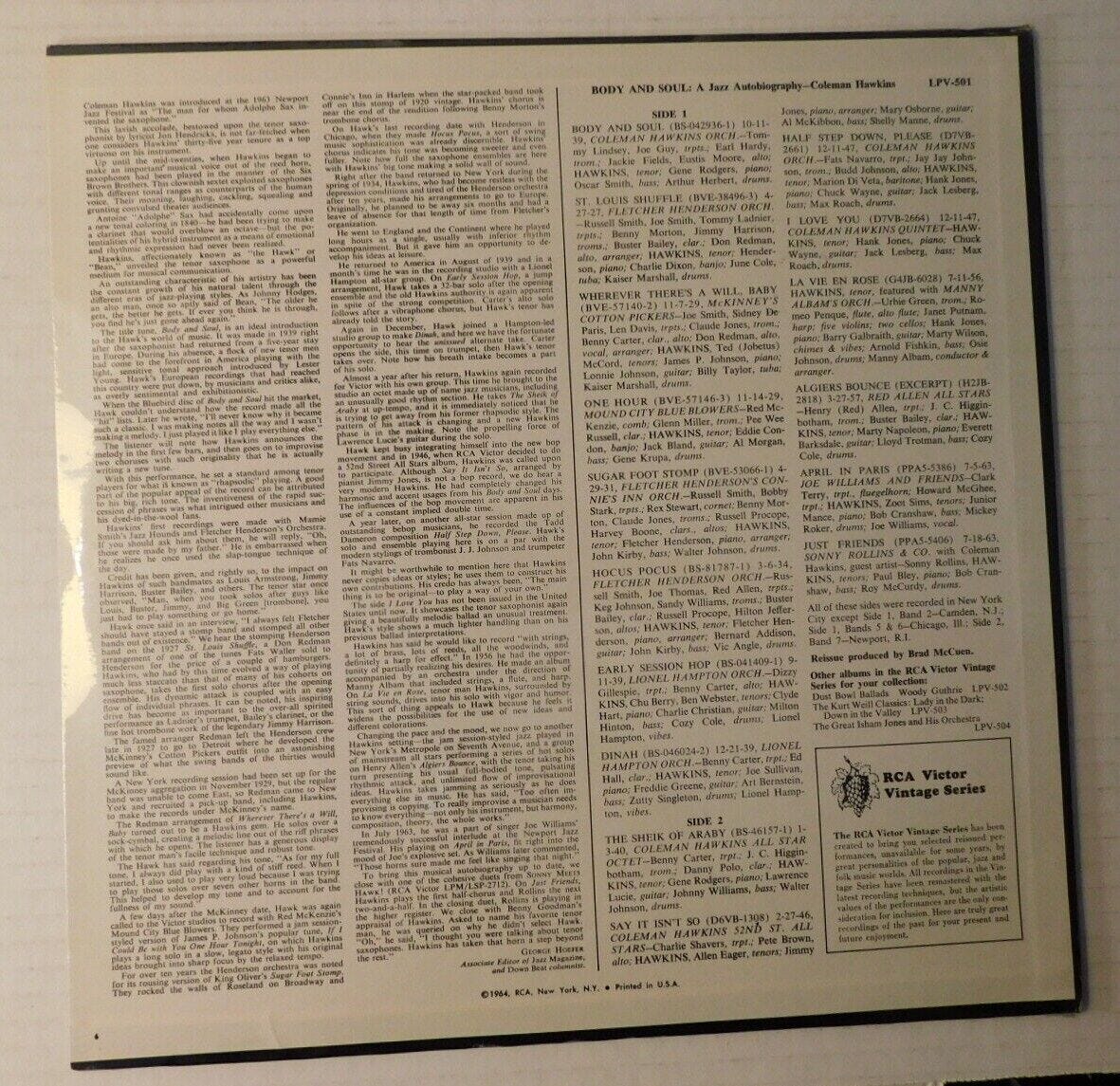

Some of the music that had the greatest impact on me as a teenager was the piano playing of Paul Bley and saxophone work of Sonny Rollins, both together and separately, as recorded in the 1960s. Sometime in the past 30 years, it has become an accepted fact that Bley’s solo on “All The Things You Are” from the album that he and Rollins did with Coleman Hawkins is a classic. I agree now, but I did not know that solo as a teenager. In fact, I only knew the shortest track on the album, “Just Friends,” because one of the first albums I ever bought, on the recommendation of New York Times jazz critic John S. Wilson (you can see his list here) was an anthology of Coleman Hawkins tracks, and they could only fit a short piece at the end of Side Two:

But although it was not selected for musical reasons, I felt then, and still today, that that track has some amazing things on it. It conveys a tremendous amount of what I call “musical information.” And one moment will definitely blow your mind, so keep reading.

The album Sonny Meets Hawk! was recorded on two days in July 1963, just about a week after the two saxophonists had played a short set together at the Newport Jazz Festival. (Producer George Avakian told that part of the story in a magazine article, below for paying subscribers.) As it happened, this was during the period when Rollins was playing particularly “way out.” He had just toured the world in a quartet with Don Cherry on trumpet, and then put together a quartet with Bley on the piano. Both Bley and Cherry had performed with Ornette Coleman, whose music was of great interest to Sonny.

But I would like to reject right off the idea, which you will sometimes read, that by playing “out” Rollins was in any way trying to make fun of Hawkins, or trying to make Hawk feel old or outdated. Rollins absolutely idolized Hawkins from the time he was a youth. He even sent a fan letter to Hawkins after seeing him perform in October 1962. The text of the letter appears on page 392 of Aidan Levy‘s terrific Rollins biography. (Paying Subscribers, you can see the actual handwritten letter below.)

Did Rollins behave strangely during the recording sessions? Absolutely. He was noted for odd behavior during the 1960s. For example, he didn’t show up at all on the first scheduled date. And when he finally did come to the studio, at one point, after a couple of attempts to play “Satin Doll” with Hawkins, Rollins interrupted and yelled “No, no, no, no, no!” But none of this reflected any disrespect for Hawk. It probably had more to do with the pressure that Sonny was feeling, being in the position of recording with one of his mentors. And despite awkward moments like that on the outtakes, there are many successful, even inspired, passages on the released album. The moments that work, really work—they are magical.

I have listened to the session tapes for “Just Friends,” and I noticed that the released track was assembled from two takes, as follows:

Piano intro from take 2

Hawkins first half-chorus (16 bars) from take 2.

Splice at 0:29. Rollins second half (16 bars) plus solo, from take 3

Piano half-chorus from 3

Hawkins half-chorus, plus solo chorus, from 3.

Splice at 3:14. Both saxes duetting, from take 2.

Splice at 4:25 to end: For the ending of the duet between the two saxophonists, which happens over a vamp, they recorded an extra take of just that vamp section and inserted it (therefore this is called an “insert”) at the end. This track was then faded out by Avakian and the engineer.

In short, the entire body of the track, from Rollins’s first notes until the saxes playing together near the end, is the bulk of take 3, unedited. (These types of editing decisions were usually made by the producer and the audio engineer, listening together without the musicians present.) But for the sake of our discussion, I’m not going to remind you where the splices are. They are really not noticeable, except for the one at 4:25, and even that one will only stand out because I told you about it. And in any case, the issued version is, after all, the finished product—that is the recording that we know. Many classic recordings are full of splices—like it or not, the editing is part of the work of creation.

Let’s listen now, starting with Bley’s 8-bar introduction. It sets a mysterious mood. It establishes right from the start that they’re not going to be playing strictly by the rules, so to speak.

Hawkins plays the first half of the first chorus, and then at 0:29 Rollins comes in for the second half and continues into a new chorus at 0:47 by building on the few notes that he just used to end the theme chorus. Some people have had trouble making sense of this solo because it might seem disjointed at first hearing, but to me, it’s a rollicking, funky, bluesy and percussive approach to “Just Friends.” If you think of it that way, instead of looking for Charlie Parker to suddenly appear, you will really enjoy it. I also love Sonny’s tone here, dark and bassoon-like, especially in his lower register.

What a great, dancing line Sonny plays at 1:00! He proceeds into his second chorus at 1:22. Bley stopped playing at the start of Sonny’s solo at 0:47, but there is plenty of momentum provided by Roy McCurdy’s drums and the driving bass of Henry Grimes. (The LP above mistakenly lists Bob Cranshaw, who plays bass on other tracks of the album.) Bley returns behind Sonny at a crucial moment at 1:35 while Sonny finishes his solo on a long high note.

At 2:00, Bley gets just 16 bars, a half-chorus. These bars are beautiful to me, especially the way Bley ends on a descending pattern. Now Hawkins comes in, totally unfazed by the wildness of Bley and Rollins. Hawk finishes that chorus and plays a full second chorus starting at 2:36.

Then at 3:13, the two saxes duet for two choruses, and this is my favorite part , because what Rollins plays here is so intensely lyrical. Listen to him, for example at 3:28 and 3:44. I just love that last one – what a great and bluesy way to propel the music into the next chorus!

Here are those three Rollins phrases that I just singled out—at 1:00, 3:28 and 3:44, in that order. (Each one begins with a few seconds of silence.)

And here’s that astounding moment that I promised you: At 4:00 Rollins plays a diminished scale pattern, which in itself is very cool. (Coltrane was famous for playing such patterns at lightning speed in 1957 and ‘58.) But listen again— he leaves one note out and it’s the piano that plays the missing note, E-flat, at exactly 4:05. I know this is hard to believe, so I am asking you to listen again—here is that moment singled out. You’ll hear it three times, first at full speed, then at .75, and then at half-speed:

Did Paul simply hear where Sonny was going? But how did he know that Sonny would leave that note out? Why didn’t they both play that note? Was this a routine that they had rehearsed and used on other occasions? If so, it’s not recorded anywhere else. And why would they do it? Just being silly, having fun?

Is it even possible that Sonny and Bley both did play the note, and that either Avakian or Sonny decided to edit out the saxophone note and leave the piano by itself? If so, did Bley play the note as a way of saying to Sonny, “That’s the one thing you played that was predictable”? Or did Sonny hit a wrong note (for the particular pattern that he had started), and someone decided later on that it would be fun to go back and let Paul dub (aka “punch”) in the correct note?

No matter what the answer is, it’s pretty amazing!

All the best,

Lewis

(Paying Subscribers, keep scrolling down for two bonuses please!)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.