Stuff Smith: Two Unknown Recorded Songs, Louis Prima, and A Web of Composer Credits—Guest Post by Anthony Barnett

[I love Stuff Smith’s high energy and highly original jazz violin playing. Anthony Barnett is a poet, editor of the literary and arts print journal Snow lit rev, and a jazz historian specializing in violinists who has published books and articles and uncovered many previously unknown recordings, all available here. He previously shared research on Eddie South and Milt Hinton. Here he presents the audio and the background of two recently discovered Stuff Smith recordings:]

Stuff Smith: Two World War II Songs, Louis Prima, and the Tangled Web of Composer Credits

By Anthony Barnett

Stuff Smith composed or co-composed two known songs about World War II. Only recently have airchecks (recordings of radio broadcasts) of both surfaced, courtesy of filmmaker and jazz collector Harry Arends. In 2024 he purchased a stash of discs whose origin can with certainty be traced back to Smith’s personal manager at the time, Barnard “Barney” Young.

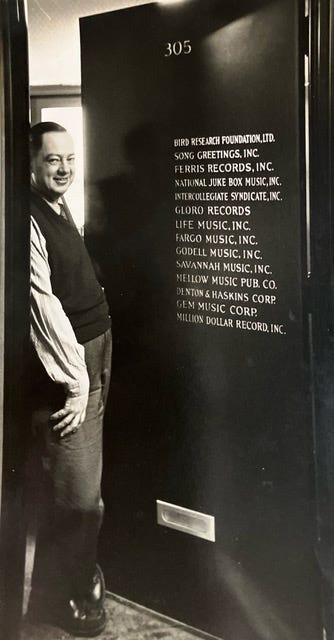

The first song is “Three Cheers for F. D. R.” (Franklin D. Roosevelt). Published sheet music has long been known. The copy, without illustration, reproduced below is in my AB Fable Archive. It is a four-pager of which the fourth page is blank. It was published by Barney Young in 1942. It is unusual, possibly unique, in that it bears Young’s name as publisher, instead of one of his many companies, some of which were listed on his office door:

The composition is credited “Words and Music by Barney Young, Leroy (Stuff) Smith, Louis Prima and Edgar Battle” and, as we shall see, because it includes Prima’s name, it surely must post-date the aircheck. Here is the sheet music:

The aircheck, recorded off the radio by Frankay & Jackson studio, is performed by Louis Prima and His Orchestra, on a broadcast over Station WJZ, then located in N.Y.C., at 11.15pm on April 20, 1942. In fun, Prima takes a few liberties with the words that you saw above in the PDF. For example, he calls the Axis leaders “characters” instead of written “gangsters”:

The aircheck disc label reads “recorded for Bomart Music Co.," a Barney Young company, with his brother Morris Young. Bomart still exists, subsumed under the Boelke-Bomart name. Two different mock-up illustrations for sheet music covers—one bearing the name of the long-established T. B. Harms company, but believed to be unpublished— reproduced below, reveal that Barney Young wrote the words, while Stuff Smith and Edgar Battle (who has arranger or composer credits on some released Prima recordings) wrote the music. Prima is not named:

It makes sense that Battle would have taken the composition to Prima. Note that Prima’s name comes before Battle’s on the published sheet music above, the PDF. Probably, that was Prima’s “fee” for broadcasting the piece, which was a typical practice among performers.

It is cause for comment that Smith and Battle still worked together at this time, because Smith noted on the box of a ca.1966 tape dub of his 1940 recording of “Crescendo in Drums” that Battle “stole it.” This refers to Battle’s composer (instead of arranger) co-credit, along with Smith, Clyde Hart (Smith’s erstwhile pianist), and Cozy Cole, for whom the tune was written, on the label of Cab Calloway’s 1939 recording:

Another curious composer matter: Young and virtuoso marimba and singing glasses player Gloria Parker (who were for a time engaged) are co-credited on Stuff Smith’s September 1944 recording of “Stop–Look.” But on Smith’s V-Disc of the song (incorrectly labelled “Stop–Look–Listen”), recorded the same month, Smith alone is credited. And for yet another instance, we may wonder why Young had Chappie Willet’s studio make an aircheck of Smith’s performance of the short-lived 1939 hit “Big Wig in the Wigwam,” until we learn that one of the three composers, Byron Bradley, is Barney Young. Yes, Byron. What a tangled web Barney Young seems to have spun, although, to judge from their apparent loyalty over quite a few years, he may have treated those he represented better than some other personal managers, many of whom also put their names on songs.

“Three Cheers for F. D. R.” was not Barney Young’s only song for a president. Five years later, in 1947, he co-composed a celebratory “Truman Flew to Mexico” with Parker and prolific Soundies producer and director William Forest Crouch. Extant correspondence, in which Young describes it as a “folk song,” reveals that he mailed a private recording, on which Parker is the vocalist, to Truman. If sending “Truman Flew to Mexico” to Truman is anything to go by, it does seem likely that Young would have sent “Three Cheers for F. D. R.” to Roosevelt.

The second song is “V for Victory.” It is preserved on an aircheck dated, on a slip of paper in Barney Young’s hand attached to the disc, September 1944, along with what appears to be a question mark over whether or not it should be published. (By this time Young appears to have had access to recording equipment and was able to dispense with the services of outside studios.) It is believed to be composed by Stuff Smith alone. (It is not the song of the same title sung by Laurel Watson with Cootie Williams, New York, mid-June 1943, from the Columbia Pictures short Film Vodvil.) Smith’s novelty singing, transcribed below the audio here, is rather in the manner of his 1936 “I’se a Muggin’ ” (or indeed Prima’s 1940 “Sing-a-Spell”). [Lew notes: First you’ll hear the announcement for someone else performing “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby?” Then, Smith talks with the host and performs “V For Victory.” There’s an excellent guitar soloist while he sings—probably Danny Perri, as explained below—and then Stuff takes a great hard-swinging solo at the end.]

Smith (spoken): Whip it now, come on! (Pause) Come on!

Smith: Now Boys,

Band: Yeah man!

Smith: Boys

Band: Yeah man!

Smith: I’ve got a dance and it’s brand new,

You don’t use your feet.

Band: Well, what do you do?

Smith: You take one hand and you do like this. (Lew notes: He moves it in a circle, palm facing forward—this was a current dance.)

Take the other hand and you do like that.

All of a sudden you get in a trance—

Look out man, that’s the Victory Dance.

V—now V stands for Victory.

I—I am an American. (Someone else says “Um Hmm.”)

C—well C, that means that is my country.

And T—T means I’m true. Yeah!

O—O, that’s the Orient. (Someone else says “Uh Huh.”)

R—R means you’ll never rule.

Now Y—Y, that’s yours truly.

So don’t take us for sale for a fool.

Now look out Jap, We ain’t jivin’, Look out Jap, we ain’t connivin’,

Look out Jap, no use strivin’, Gonna take you off the lap and off of the map.

Look out Jap, We ain’t foolin’, Look out Jap, you need some foolin’,

Look out Jap, We’ll do the rulin’, ’Cause East and West will never meet.

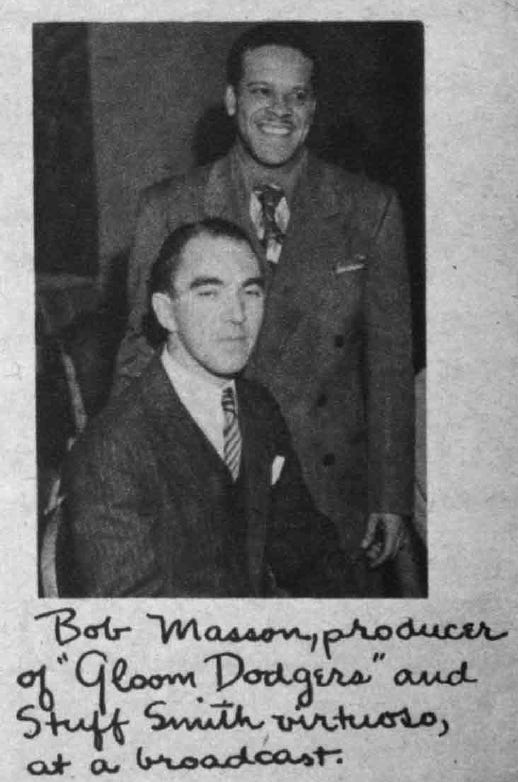

The source of the aircheck is not known for certain but it could well be the WHN New York radio series Gloom Dodgers (as in, "this show will make you dodge, or avoid, a gloomy mood"). Smith frequently guested on that show, as did, for example, fellow violinist Eddie South, and Barney Young client Una Mae Carlisle. (Una Mae was Stuff Smith’s 1940 nemesis over another authorship tussle, the press-reported “Walkin’ by the River,” in which Young sided with her.) In fact, a photo, reproduced here, of Smith “at a broadcast” with Gloom Dodgers producer Bob Masson appeared in The New Baton, vol. 1, no. 5, New York, February–March 1945, p.12, under the rubric, over two pages: “Baton’s Photo Album / Photographs by Barney Young and Phil Gottheil”:

Smith’s unidentified accompanying musicians on the aircheck are a prominent guitar soloist, piano, bass, and drums. They are more likely to be the program’s house musicians than Smith’s own, whose well-established and well-recorded working group at the time was a trio with pianist Jimmy Jones and bassist John Levy. In any case, the aircheck pianist does not sound like Jones. If the program is indeed Gloom Dodgers, then the studio orchestra was led by Don Bestor, and Don Albert (not the Texas trumpet player of the same name) was the program’s musical director. In that case there is good reason to believe that the guitarist is Danny Perri, the pianist Sammy Fidler, and the bassist Anthony Federici, because all three plus Eddie South appeared on a 1945 Musicraft session behind country singer Dave Denney, under the direction of Albert. Furthermore, Denney was another regular guest on Gloom Dodgers.

[Lew adds: Domenico William “Danny” Perri was born in Toronto, Canada on April 20, 1915. He made his way to N.Y.C, and sailed from there to England in October 1936 to accept an offer to join the famous Jack Hylton band. While there he met his wife and they married in 1937. In August 1939 they both arrived back in New York and by January 1940 he was working with the Jack Teagarden orchestra. From about April of that year he was in Jan Savitt’s band for around two years, and he later was a prolific studio artist on radio and on recordings, often paired with bassist Bob Haggart, behind many singers, including one session with Billie Holiday, several with Ella Fitzgerald including her famous 1947 “Oh, Lady Be Good,” and many with Perry Como. He and his wife lived in Manhattan for many years, then moved to Great Neck, N.Y., where he died in March 1975. Overall, he was a very successful musician, but worked mostly in settings where he was an accompanist, not a soloist. However, Anthony found a recording where he is featured and it clearly resembles the guitar work above. Back to Anthony:]

I cannot claim that either song is particularly memorable from a musical point of view—probably they were not meant to be, though they are both catchy and serve their purpose. But they do offer insights, different from what is mostly known from, for example, V-Discs, into how jazz musicians engaged with World War II. At least there is a good Smith solo on “V for Victory,” and it is no bad thing to hear Louis Prima’s big band during a period when he was not recording: the Petrillo recording ban, basically a musicians’ strike, came into effect two months after the aircheck, lasting through to 1944. We don’t know Prima’s personnel here (there is an appropriately fired-up tenor sax solo) but the well-featured drummer is likely to be Jimmy Vincent, whose long sojourn with Prima began early in 1942, in which case this would be his first known recording.

Anthony Barnett

P.S. My grateful thanks to Harry Arends, and to film historian Mark Cantor (who facilitated contact with Harry), Timothy Buchanan (Una Mae Carlisle specialist), Charles Young (for documentation including cover mock-ups), Michael Fitzgerald, Kevin Coffey, and, for information about Prima and Vincent, Tony Middleton and Richard Vacca. Photo of Barney Young courtesy Charles Young. My thanks too to Lewis for transcribing the words to “V for Victory”.

[Thank you Anthony for the entertaining words and music! Readers, don’t forget his jazz violin website.

All the best,

Lewis

Very careful listening to The Victory Dance aircheck will reveal that the name "Jack", is not correct.The word "Japs" appears five times in the song,just as plain as day to me.One listen was all it took for me to realize this.Let us all consider that the ridiculous and absolutely unnecessary concept of "political correctness" just did not exist until only a few decades prior to our current era,and that the war in Europe did not become World War Two until President Roosevelt declared war against Japan,after the "Japs" had destroyed Pearl Harbor in a reprehensible sneak attack on December 7,1941.So it is "Japs" in the lyrics of the song.

I've loved Stuff's playing since discovering him many decades ago. One of many things I dig about Regina Carter is how wonderfully she can channel him when she chooses. Stuff was born just 50 miles down the Ohio River from me.