It seems that every person has a favorite story about the origin of the word “jazz”—and an agenda to go with it. Some people would like the word to come from Africa, so they firmly believe the stories that support that. Others want it to be a Black American word, so they look for that. The saxophonist Archie Shepp has lived in Paris for many years, and he has not the slightest doubt that “jazz” is a French word. There is a group of people of Irish descent who fervently want to believe that it comes from the Irish language. But, as we will see, all of these ideas—and many others— are wrong. To be more specific, they have no basis, no foundation.

People seem to think that in order to discover the history of a word, you only have to sit back until you hear an explanation that “sounds right” to you. I constantly meet people who say “My friend told me that the word ‘jazz’ started this way.” But this kind of work is conducted by professional researchers. They study thousands of written documents and analyze them, applying their knowledge of how words are formed, how they spread, and how they influence each other. (In tracing word origins before the invention of sound recording, writings are of course our only evidence.) Linguists (scholars of languages and their history), etymologists (researchers of word origins) and lexicographers (dictionary researchers) have been on the case of “jazz” for decades. Many of these experts belong to the American Dialect Society, and they have been kind enough to include me in some of their listserve discussions over the past 20 years. (I will thank a number of them in the course of this series of essays.)

Originally I planned to simply write a short summary of what is known. But in the process, as is usual for me, I did an extensive study. I ended up reading through literally hundreds of printed materials from the 1800s and early 1900s. I came up with a number of new thoughts, and even some new evidence. So there will be seven essays in this series. I have just about completed all seven, but I will not post them all in a row, so as to keep this Playback series interesting and varied.

Today we will begin with the origin of the word “jazz.” But I won’t keep you in suspense. I will tell you the conclusions up front. While I will present some new details, the Bottom Lines in this discussion are unchanged from what the researchers have been saying for years:

1. The word “jazz” is first documented in 1912, and it evolved from a slang word, “jasm,” sometimes spelled “jazzum” or “jassum,” meaning liveliness, “pep,” energy, intensity, and related concepts.

2. All Other Tales about the origin of the word “jazz” are 100% false and are not supported by any evidence or research. Yes, I said ALL. That’s the simple truth about all the other stories that have circulated. But in the last essay of this series we will look at a few of those, just to provide you with more information as to what’s wrong with them.

3. It is not true that the word was originally spelled “jass.” From 1912 on, it was spelled equally “jazz” and “jass,” and sometimes other spellings such as “jas” and “jaz,” until the “...zz” version became standard during the early 1920s.

4. Initially the word was not connected with music. A few months before July 1915, “jazz” was recognized as a type of music in Chicago and possibly California and elsewhere. Bands started using “jazz” in their names soon after, and by December 1916 that was common. The music was named “jazz” by white Americans, as Ellington, Max Roach and many other older musicians correctly claimed. And it was a compliment, not an insult. It meant that the music was lively and energetic.

5. The word was not invented by American Blacks and it is not from New Orleans. Therefore, it does not come from African languages, nor from the French as spoken in New Orleans.

Now, let’s delve into the details:

If you have read about the word “jazz” before, the first point above should not surprise you. It has been known for perhaps 50 years that “jasm,” which meant energy, spirit, “pep,” vitality, was the likely ancestor of “jazz,” which had the same meanings. But there were two reasons that it was difficult to be certain: One is that the source word, “jasm” aka “jazzum” or “jassum,” is no longer in use, making it harder to research. (Essentially, “jazz” replaced “jasm.”) The other is that “jasm/jazzum/jassum” was apparently never very common, even when it was used. The evidence is that in many of the printed sources, over many years, the authors feel compelled to explain what it means.

For both reasons, the evidence was scarce. It was hard to say that one word led to the other when they were only found in sources that were many years apart. Gerald Cohen, Professor of Foreign Languages at Missouri University of Science and Technology, specializes in the etymology of words and has led the search for origins of “jazz.” He collected just about all the printed references known as of 2015 into a 194-page monograph. However, as even more writings have been digitized, recent research, especially by etymologist Barry Popik, has uncovered dozens more uses of these words, enough that we can now follow a clear path, a good “paper trail,” from “jasm/jazzum/jassum” to “jazz.”

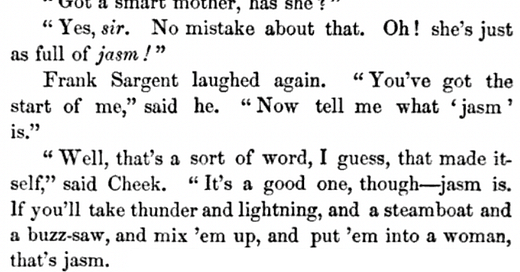

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which is considered to be the most reliable and complete dictionary of the English language, and is constantly updated by a team of researchers, traces “jasm” back to 1860. That year, J. G. Holland (1819-1881), one of the most celebrated writers in 19th-century America, used the word in his novel, Miss Gilbert's Career (p.350):

The fact that Holland has his character Frank ask what “jasm” means shows us that it was new, or at least not widely used. It’s a kind of poetic description of course, not a dictionary definition, but one gets the idea that it relates to energy, excitement, and intensity. The “buzz-saw” metaphor apparently comes from the “zz” sound in the word, and that continues to show up in the early examples located by the experts. As I said, the word apparently never caught on widely, because people were still explaining it decades later.

As for the origin of “jasm” itself, it’s possible that that may never be known. Sometimes one comes to a dead end in etymological research. One can’t simply follow every word back in time indefinitely to a handful of original words, because new influences constantly enter the picture from other languages. However, it has been suggested that “jasm” is a variant of “gism,” which originally had the same “liveliness” meaning and can be traced back a little further. The OED has an example from 1842, and researcher Bonnie Taylor-Blake has found instances going back to 1830. But “gism” and “jasm” appear to have eventually gone their separate ways— they became two independent words. By the end of the 1800s, the “vitality” meaning of “gism,” stretched to mean “virility,” meant that the word was also used as slang for “semen.” Today one still finds “gism” or “gizz” used to mean “semen.” But—and this is important—”jazz” was not used in a sexual sense until 1918 and beyond, after it was already identified with our music. That is, the sexual meaning was not part of the origin of the word, but something added later. So the Bottom Line here is that “jasm” did not suggest sex and neither did the word “jazz” originally. (There has also been a proposal by Douglas Wilson that “jasm” may have been derived from the ending of “enthusiasm,” but no evidence has turned up. On the contrary, old publications sometimes define “jasm” as, among other things, “enthusiasm,” without noting any connection between the two words.)

Now, Popik and Cohen have been tracking “jasm/jazzum/jassum” during the years before the word “jazz” first appeared in 1912. There are now so many items that it would take too long to look at them all, so I’ll just show you a few of the most entertaining and relevant ones. You just saw the one from 1860. In 1878 it was used to refer to a noxious gas, and this time it was spelled “jazzum,” which as we will see, is significant. That usage relates to the “intensity” meaning of the word, but it’s also an early example of how the word began to be used very broadly.

On May 24, 1884, in the University of Michigan’s student paper, someone anonymously published a poem about the word “jasm”! Here’s how it begins—notice that the saw comes up again, and that again there appears to be a need to explain the word, albeit in a fanciful way:

(This was in The Chronicle. That preceded the Michigan Daily, which has been the campus paper since 1890.)

The author used the pen name Brunonia. The root “brun” indicates “brown” in Latin, and to this day alumni of Brown University are called Brunonians. That might possibly be significant, because the word appears in the Brown student paper in 1885. And in 1890, Elisha Andrews, then President of Brown University, used the word “jasm” in an address delivered before the Boston Congregational Club. He defined it as “The ability to get on and ‘get there’ as seen in plans, pluck and perseverance.” The word was evidently still scarce enough to require an explanation. And this is also proof that it had a totally separate history from “gism.” I guarantee you that no college president would have spoken about “semen” to a congregational club in Boston in 1890! “Jasm” simply did not have that meaning, and not even that connotation.

In 1900, the same Mr. Andrews, who had moved on from Brown, was credited with having introduced this word to his audiences, again invoking the sound of a saw. An anonymous author in the Los Angeles Times remembered Andrews using it in a speech in Boston, and the author spelled it, by ear, as “jazzum.” (Los Angeles Times 29 June, 1900; thank you to Barry Popik and to Fred Shapiro, editor of the New Yale Book of Quotations and the leading contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary):

The same meaning and spelling appeared anonymously in nearby Riverside, California on August 31, 1900 (Press and Horticulturist, p.4): The American spirit, it says, is “the ‘jazzum,’ the ‘get-there’ spirit.”

Clearly, the word was still rare, because Andrews not only referred to it as “new” but took the credit for coining it. We know that he did not coin it, because our examples go back to 1860, when he was only 16. But he surely may have been instrumental in spreading the word. In fact, in December 1903, Andrews was introducing the word in Nebraska, where he was now Chancellor of the University. He gave a speech that was reported in a local newspaper as follows:

(From The Norton Champion, Norton, Kansas, Dec 3, 1903. There’s no author listed for this one either. It was common to omit that credit when the author was the editor or a staff person. That was even true at Time magazine in the 1950s.)

Partly thanks to Andrews, the word was finally getting around. In 1909 “jasm” appeared in The Trailers, a novel by the New York-based poet Ruth Little Mason (1883-1927). Here it means “spunk,” boldness, and energy—and notice that she doesn’t feel the need to define it:

But as late as 1915, “jasm” was still being discussed as a new creation, again compared to a “buzz saw” cutting through nails and still meaning “pep” and “ginger.” And yet another college president claimed to have coined it, George Vincent of the University of Minnesota. (“‘Jasm’: A Needful Thing,” Pacific Rural Press—a San Francisco weekly—Volume 90, Number 10, 4 September 1915, p.219.)

Now, Bonnie Taylor-Blake points out that in the Brown 1885 noted above, the author wishes for a rowing crew with “jasm,” and the Riverside 1900 piece mentions the value of “jazzum” on the “athletic field.” Meanwhile, in California the word became shortened to one syllable. After all, in speech the "um" might easily be elided or go unheard (as noted by Jonathan Lighter, author of the Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang). And the association with athletics might be significant, because in 1912 and 1913, we find the shorter version—our word “jazz—in California baseball circles! The earliest instance yet found is from the L.A. Times (discovered by George A. Thompson). It’s an article about Oregon’s minor league baseball team of that era, the Portland Beavers, who were training at Washington Park in Los Angeles for their first game of the season the next day, against the Los Angeles Angels. (This was a minor league team that ended in 1957, not the major league Angels of today.) White baseball player James Benjamin “Ben” Henderson (1883-1951) of the Beavers is mentioned. (He should not be confused with Ben Henderson of the Negro leagues, who was active later, in the 1930s.) On April 2, 1912, author R. A. Wynne quotes Henderson describing his new pitch as a “jazz ball”:

(Sofetly is a typo of course.) “You can’t do anything with it” means that it's too lively, too full of “jazz,” for someone to hit it.

So let’s see—we’re now able to trace “jasm” from 1860 to the early 1900s, we’ve seen it spelled “jassum” and “jazzum,” we’ve seen it travel around, and we’ve seen it shortened in California to “jazz.” All that time the words refer to energy, enthusiasm, and so on. And, to be sure, this meaning is still common today, as when people say “Let’s jazz this place up”! But there’s much more to this fascinating detective story, as you’ll learn in the following essays. We will discuss details of its use in baseball, how it began to spread outside of California, how it got connected with the music we love, and more.

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. Thank you to Gerald Cohen, Barry Popik, and various member contributors to the listserve of the American Dialect Society.

Back in 1988 I did an interview with Miles Davis who told me he had never heard of the word jazz before… 1949 (!) Before that he didn’t know what that was or what it referred to. It’s only in Paris in May 49 when he was billed at the “Festival International de Jazz” that he understood what people meant by “jazz”.

“Ain’t that something?” (He would say.)

Thanks for this wonderful job!

An impressive job. And needed. Thanks.