Vocalese, 2 of 4: First Recordings of Eddie Jefferson and King Pleasure, With New Info (+Bonus)

(Paying Subscribers, Eddie Jefferson’s two rare recordings are below as a bonus.)

In the first essay of this series (see the Index under “Singing”), we discussed the origin of the name “vocalese,” and we studied the earliest example that was released, by Marion Harris in 1934. In Supplement 1A, we mentioned the even earlier version recorded by Bee Palmer in 1929, but never released until 1997. It appears that vocalese was pioneered by these two women, with Harris doing her own lyrics and Palmer performing words written by Ted Koehler—both inspired by the popularity among musicians, white and Black, of the Trumbauer and Beiderbecke solos on the February 1927 recording of “Singin’ the Blues.”

Now, let’s look at modern “post-bebop” vocalese: In the early 1950s, Eddie Jefferson (1918-1979) and King Pleasure (birth name Clarence Beeks, 1922-1982) were the first to record modern jazz vocalese, followed a few months later by Annie Ross (1930-2020).

But Jefferson said he was putting words to recorded sax solos as early as 1939 (Lester Young with Basie on “Taxi War Dance”) and 1940 (Chu Berry with Calloway on “Ghost of a Chance”). And Pleasure was very clear in saying that Jefferson came before him: In 1960, he wrote in the notes to his album Golden Days, that he was aware of Eddie creating vocalese lyrics as early as 1946. In Pleasure’s words, Eddie “created the embryo of a vocal innovation in jazz…[I] developed Eddie’s baby and delivered it to the public.” Neither of them knew about Marion Harris’s recording. Jefferson did mention Leo Watson, a wildly inventive scat singer who did not do vocalese but encouraged Eddie to do something with words.

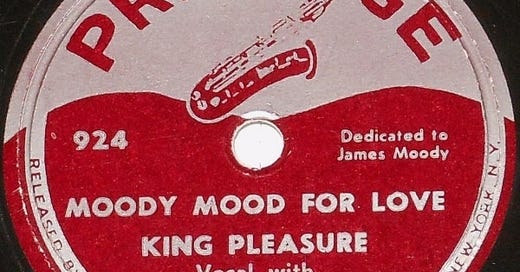

But there is confusion about whether Jefferson or Pleasure recorded first. Pleasure’s first recording date is definitely known to have been held in New York for Prestige Records on February 19, 1952. He recorded two songs, one of which “Moody’s Mood for Love,” based on a James Moody solo, became a hit. As Pleasure himself acknowledged, this was Eddie’s vocalese, and he had learned it from hearing Eddie perform it. Since Moody’s solo was on the chords of the popular song “I’m in the Mood for Love,” there was—and still is— kind of a grey area in copyright law as to who would own the composing royalty. Moody’s label gave credit to Jimmy McHugh, who wrote the original song’s melody—even though Moody doesn’t play it—but not to lyricist Dorothy Fields, since there is no vocal. But Prestige avoided crediting (and paying) Moody by omitting the composer credit completely, and called it “Moody (sic) Mood for Love,” which sounds a little less like the original title. (Moody later said they should have called it “Moody Mood,” or “Moody’s Mood.”) On the label they did write “Dedicated to James Moody”:

This kind of approach—hiding the copyright source just a little— can work with an obscure recording that nobody notices. But once this song became a hit, everybody knew that it was based on “I’m in the Mood for Love,” and the publishers of that song sued and won, thanks to a sympathetic judge. This stopped Prestige from selling the recording again until 1968, when they agreed to release it on LP under the name “I’m in the Mood for Love”! I’m not saying that’s fair, but that’s what happened. (By the way, “Teacho” on the label refers to Black, Barbados-born George "Teacho" Wiltshire, who was a producer for Prestige at the time and plays piano on the recording.)

Now, in contrast, Jefferson’s first time in the studio is relatively undocumented: The British label Spotlite in 1979 released an LP of rare jazz vocal recordings, including two previously unissued songs by Jefferson for which the dates and personnel were unknown. One was based on “Parker’s Mood,” the other on “I Cover the Waterfront.” The information given on the L.P. (and later, on the CD version) was as follows:

This information has been repeated everywhere since then. And these recordings have never been issued on another label, which might have prompted more research. But the LP producers overlooked an important clue, and to find it all one has to do is listen to “Beautiful Memories,” and, instead of guessing, actually compare it with Young’s versions—there are several—of “I Cover the Waterfront.” They don’t match at all, not even the first notes—because Jefferson’s vocalese is not based on any of Young’s recordings, but on the version of “Waterfront” by, once again, his favorite, James Moody. But Moody’s version was recorded in Paris on July 27, 1951, and I cannot find any references to it in print before January 1952, so it appears that it was not available in the U.S.A. until late December or early January. That means that the estimate of “1949/1950” or this Jefferson recording is way wrong. And, since Eddie could not have heard the Moody recording until the end of 1951, it’s hard to believe that he could have composed his words to Moody’s solo on “Waterfront,” and managed to connect somehow with a recording company and arrange a recording session, before Pleasure first recorded on February 19, 1952.

But there’s more. Subscriber and researcher James Accardi points out that the catalog (a.k.a “matrix”) numbers assigned to the two Jefferson songs—HL 355 and 356—must refer to Hi-Lo, which was the first label known to record him. And the numbers are in line with items that Hi-Lo only released in late 1952. (Recording companies always assign these numbers in order.) For example, just before Jefferson’s matrix numbers, 353 was a recording by one “Mr. Blues” Carson that was recorded November 26, 1952, so was probably released in December. That means that the Jefferson sides would not have been released before late December 1952, or January 1953.

But in fact, I can find no evidence that these two sides were ever released at all. I don’t know of a single collector, or any site on the internet, that can show an issued disc containing these two sides. If in fact they were not released, then the Spotlite producers were working with a test pressing or acetate. (Malcolm Walker, the only surviving person who was once involved in that label, recently told me that he designed the LP jackets, and didn’t choose the recordings.)

And finally, Jefferson consistently said that his first recording session, for Hi-Lo, which has a known date of July 11, 1952, came about only after King Pleasure recorded in February, as a result of Pleasure’s generosity. That is, Pleasure told Prestige producer Bob Weinstock that Eddie had written “Moody(‘s) Mood” and encouraged him to record Eddie, which Weinstock did by going to Eddie’s hometown of Pittsburgh and using the Hi-Lo label, with which Bob had contacts. So, according to Eddie himself, there was no session before that one. And that session produced four known sides that were released in the fall of 1952: Their first mention in the press is on August 30, 1952 (Cash Box magazine), and there are several later ones including Metronome in November.

All of this got Accardi thinking—maybe there was only one recording session in Pittsburgh, and the two mysterious songs are “leftover” titles from that one session. I took James’s idea and ran with it as follows: Every Hi-Lo session other than Jefferson’s first was made in N.Y.C., so it does seem unlikely that Weinstock traveled twice to Pittsburgh. (Hi-Lo did later release a “live” album of the Howard McGhee all-stars from the island of Guam, but they did not go to Guam—they obtained it from another source after it was recorded.) Also, although the personnel for the two titles is not known, the backing sounds quite similar to the titles issued from July 11. The only difference is that on the two “mystery” titles there is only tenor sax and rhythm section, whereas on the four released titles there is also a trombone, which plays written parts with the sax behind the singer. Also, the two “mystery” titles are both slow, and all four that were released are medium-tempo swingers. It’s likely that these two factors—the slow tempos, and the lack of instrumental backgrounds, are exactly why those two titles were not released (if in fact they were not).

By the way, the Pittsburgh recordings were made in the George Heid Productions studio on the Club Floor of the William Penn Hotel, one of the first dedicated recording studios, when most were still used for radio broadcasting as well. The musicians are usually listed as Johnny Morris (trombone), the excellent Nat Harper (tenor), Walt Harper (piano), Bob Boswell (bass), and Cecil Brooks, Jr. (drums; the father of Cecil Brooks III). Brooks confirmed his presence around 2013. But Heid Jr., son of the studio head, said that he found paperwork indicating Billy Lewis on bass, and Hal"Brushes" Lee on drums. Possibly Lee was originally scheduled, but was replaced by Brooks. At this point all parties are deceased, so it might not be possible to resolve this.

TO SUM UP: There is no reason to doubt King Pleasure’s statements that Jefferson was doing vocalese before him, and that it was Eddie who wrote the words to “Moody’s Mood.” But as far as recording, we can say that King Pleasure recorded first, on February 19, 1952, and that, partly thanks to him, Jefferson recorded next, on July 11, from which four songs were released that fall. And that an additional two songs were recorded for Hi-Lo, most likely also on July 11, but possibly on a later date, but were not released until early 1953—or possibly were never released until the producers of the 1979 Spotlite LP came across an unreleased test pressing or acetate. OK?

Now, I know that you want to hear some music after I’ve driven you crazy with these details! First, here is the beginning of James Moody’s 1951 “I Cover the Waterfront,” followed by the beginning of Jefferson’s 1952 version, which he called “Beautiful Memories.” (In the examples below I have not altered the recordings at all, but please be aware that singers often have to perform in a different key from the original recording, in order to accommodate their vocal range.)

And finally, let’s compare Jefferson’s and Pleasure’s versions of “Parker’s Mood,” the famous Charlie Parker blues recording from 1948. This is an interesting juxtaposition, because in this case each singer wrote his own words, so each one tells a different story. Of course the version by Pleasure, recorded in December 1953, became another hit for him, so those are the lyrics most people know. So, first, let’s hear the beginning of Charlie Parker’s solo, then the beginning of Jefferson’s, from, as I argued above, probably July 11, 1952. The third one below is the beginning of Pleasure’s recording.

(Paying Subscribers, Eddie Jefferson’s two rare recordings are below in complete form, as a bonus.)

Now, moving on—some of you probably know that the Delta Rhythm Boys did a pre-bop vocalese on “Take the ‘A’ Train,” and we will study that in Part Three. But film scholar Mark Cantor has just discovered two more early vocalese films of theirs! Those will have their world premieres in my fourth essay.

All the best,

Lewis

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.