Wayne Shorter's First Recordings—Never Released! Part 1, + BONUS

BONUS: RARE print interview with Wayne for Paying Subscribers

(Paying subscribers, there is another gift for you at the very bottom. ENJOY!)

Let’s pay tribute today to Wayne Shorter (August 25, 1933—March 2, 2023). He passed away the day after I posted this:

All of the reference sources, even the comprehensive database of all jazz recordings ever, list Shorter’s first recording year as 1959. They sometimes mention the “live” recording of Maynard Ferguson’s band with Wayne, made at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1959 for broadcast overseas on the Voice of America. They always mention his studio recordings in August and November 1959 with Lee Morgan and Wynton Kelly.

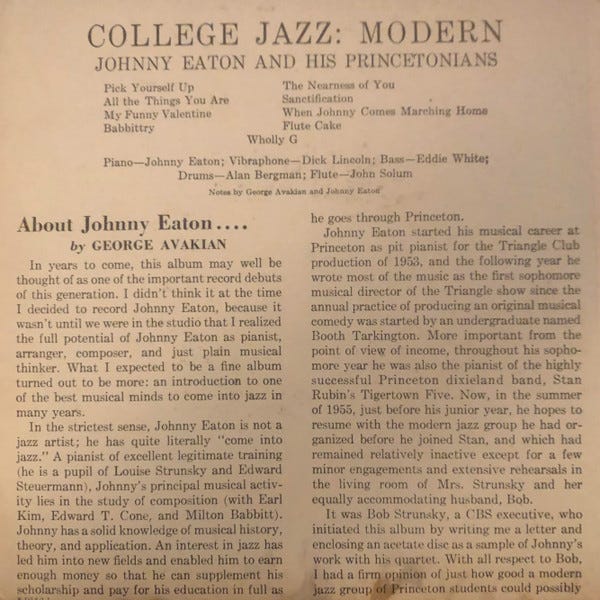

But in fact, as Michelle Mercer’s biography correctly notes, Shorter made his first recordings three years earlier, on June 8, 1956 in the Columbia Records studio on 30th Street in Manhattan, as a guest with pianist Johnny Eaton and the Princetonians. The band members were indeed all Princeton students when this was recorded, except for Shorter. Jazz had some history at Princeton: In fact, in 1924, a Princeton student group had been the first college band ever to record, I believe. (Yale was the next, with Rudy Vallee recording in 1927.)

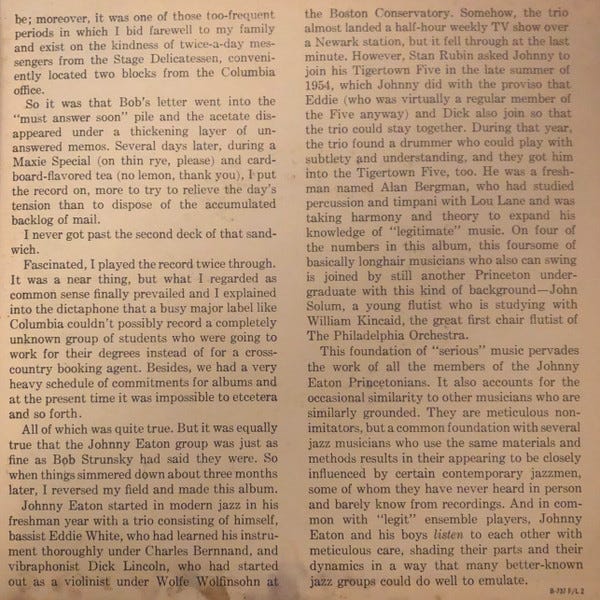

John “Johnny” Eaton (1935-2015) was primarily a modernist classical composer, and he brought the influences of his teachers Milton Babbitt, Earl Kim and others to his jazz compositions and arrangements. He had first recorded a year earlier, in June 1955. Producer George Avakian, who was then at Columbia working with artists such as Miles Davis and Louis Armstrong, told the story of how he first learned about Eaton in the notes to that first album:

Early in 1956, Eaton and his fellow students recorded five short pieces for a second album, but they needed more material. The session in June with Wayne was meant to complete the album. But those tracks were not used. My guess is that it had nothing to do with Wayne’s playing. The five tracks that were already finished featured classical flutist John Solum, and Avakian probably felt that the album would have a more consistent sound if they continued to feature the flute. And in fact, the album was filled out in December 1956 with a session that included flutist Herbie Mann. The album was titled Near In, Far Out. (If you’re interested, you can listen to College Jazz: Modern here, and to Near In, Far Out here.)

Eaton graduated from Princeton in ‘57, and returned there for a Ph.D. which he completed in 1970. In the early 1960s, he recorded two albums with clarinetist and fellow composer Bill Smith (also known for a long association with Brubeck) in an experimental quartet called The American Jazz Ensemble. To my knowledge, he did not perform as a jazz pianist after 1963, devoting himself to a successful career as a composer and music professor (mostly at Indiana University). He received a MacArthur award in 1990.

Important: There is another pianist named John Eaton, from the same generation! Born in Washington, D.C. in 1934 and still active in that area, he has a distinguished career interpreting the “Great American Songbook.” This Washingtonian John Eaton graduated from Yale in 1956, not Princeton, but still, this can be confusing.

In Mercer’s book, Eaton is described as playing Dixieland gigs and doing tricks like playing with his back to the piano. One might think, “That must be the Washington pianist.” However, it is probably the Princeton one, because Eaton and some of the other Princetonians made money playing with a fellow student, clarinetist Stan Rubin (graduated Princeton ‘55), and his Tigertown Five, a wildly popular Dixieland group. (In fact Rubin has remained a leading swing bandleader in New York for all of these years, and many musicians have worked with him, including Sonny Rollins biographer Aidan Levy.)

I first obtained the recording session with Shorter in 2007 from the drummer on the date, the late Alan Bergman (1935-2014, Princeton’58), who by then had become the leading “jazz lawyer,” representing the Monk estate, Billy Taylor, Ron Carter, and many others, as well as King Crimson and numerous famous groups. Alan identified two of the other musicians: Dick Lincoln ‘57 was on vibraphone, and he became a very accomplished engineer. He worked on the Apollo project, then at RCA's Sarnoff research laboratory in Princeton, among many other projects. Bassist Ed White ‘56 worked in international development at the United Nations for many years. These three reunited in the 1990s as part of the Princeton Jazz Quartet (sometimes Quintet).

Their trombonist in the 1990s was Tom Artin (Princeton ‘60, Grad school ‘68), who remained in music and worked with the Smithsonian Jazz Repertory Ensemble, the Louis Armstrong Alumni All-Stars, and others. And Bergman told me that Artin is on the date. But both Artin and Lincoln recently told me that Artin was not on the date with Wayne, and they don’t know who the trombonist was. And in any case, as trombonist Dan Weinstein pointed out to me, it doesn’t really sound like a trombone—it sounds like a mellophone (which sounds something like a French horn). So we will have to list the brass player as “unknown” for now. However, I’m still researching him, and will update this and post new info in Parts 2 and 3.

Bergman reminisced for me as follows:

“That actually was pretty heady stuff for us, especially for me, a kid out of Brooklyn, barely 19 and here I was at the legendary Columbia Studio. We all played with a Dixie band called Stan Rubin and his Tigertown Five and we did some pretty neat stuff with that group in the summer of '55: The Second Newport Festival, where I played on Barrett Deems’s drums and where my father's '54 DeSoto got a fender dented by Woody's T-Bird; and TV shows—the Steve Allen Tonight Show hosted by Ernie Kovacs, Ed Sullivan, and a summer TV show hosted by Stan Kenton where we played with Ella Fitzgerald!”

Alan mentioned that Rubin’s group had some “photos taken at Cornell University. We were playing up there with a tenor sax player named Scott LaFaro. It’s true—he was learning bass and was questioning our bass player Ed White about what he was playing.” LaFaro was at nearby Ithaca college staring in the fall of 1954, and while there he switched from sax to bass.

(You will read that Rubin’s group also played at Grace Kelly’s wedding, but that’s a slight exaggeration. They did play several times during the week of festivities in April 1956, but not at the wedding itself. In any case that band did not include any of the people who are on today’s featured recording date.)

Shorter had gotten to know the Princeton musicians through his boyhood friend White, the only Black member of the group. Wayne had played a few gigs with them, and then they asked him to participate in the recording session.

OK! So here is Eaton’s arrangement of “Too Close For Comfort,” a song from a then-current Broadway musical, Mr. Wonderful starring Sammy Davis Jr. After vibes, piano, and mellophone solos, Shorter solos with fleet fingers and a light tone, followed by a brief closing ensemble:

And here is Eaton’s version of “Hallelujah” at a very fast tempo, about 336 bpm. (This is the old Vincent Youmans melody of course—not Leonard Cohen!) This one shows off Eaton’s modernist arranging style, with lots of dissonance and a wild piano solo right after the theme. After vibraphone and mellophone solos, Wayne handles the high speed really well, with crisp articulation (tonguing):

There’s more music coming in Part 2! And we will compare Shorter’s playing with some of his influences of the time.

All the best,

Lewis

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.