(Paying Subscribers, a lesser-known audio interview with Hawkins is your gift, at the bottom.)

My first “memory” essay, about Pete La Roca, was one of my most popular. Here’s another memory essay. I will be posting many more. They will be included in the Index on the home page under “Porter, Lew's Memories.”

Just recently, on September 9, 2023, an historic marker was unveiled at the building where Coleman Hawkins once lived:

It was placed by a non-profit organization called While We Are Still Here that does valuable work to preserve the Black history of Harlem. Sheila Anderson of WBGO radio hosted a short ceremony at the event. I spoke briefly, as did his surviving son René and daughter Colette. Here they are:

(Their mother Dolores and sister Mimi passed away many years ago.)

Hawkins was interviewed at length on a two-LP set for Riverside Records in the summer of 1956. As you will hear, he was clearly brilliant, very sure of himself, not falsely modest, but also not boastful. Rather, he was realistic about his impact on music. He was well aware of his accomplishments. But he regularly denied that he was “the father of the jazz saxophone,” and he named some of his contemporaries in order to show that he was not the first. (He especially liked “Stump” Evans, one of my favorites, about whom I’ll be writing here.) And I love the way he expresses himself. At 1:12:40 in the link above, he said that the audiences in Denmark and Holland were “the very tops.” I heard that when I was about 15, and from then on when I liked something, I said it was “the very tops.”

I was lucky, because I got to see Hawkins perform. As I told you in my previous story, my first trip to the Vanguard was as a guest of drummer Pete La Roca in the summer of 1966. So, now I was familiar with the Vanguard, and I saw that the masterful Hawkins was playing there just a few weeks later. In the 1980s I published two books about Pres, but I was into Hawkins before I ever heard any recording of Lester Young. Among the first five jazz LPs I bought in the fall of 1964 was RCA LPV-501, whose liner notes I included in an earlier essay. This was the first in the acclaimed Vintage Series of reissues and it featured Hawkins recordings from 1927 all the way to “Just Friends” from Sonny Meets Hawk in 1963. I listened to the last track over and over to enjoy both Rollins and Bley and it had a huge impact on me, which I have written about here. To some extent it set the direction of my playing--my use of polytonality and so forth. And Hawkins had participated in all this great music for all these years, so I had to see him. So I went to the Vanguard, by myself, at age 15. I sat at a little table against the left wall, about the third table from the stage. I could show you that table today—that’s how little the Vanguard has changed!

Now, honestly, I don’t think they were supposed to let me in to the Vanguard. The drinking age in New York was 18 at that time. And I looked my age, not older. But not only did they let me in, a tall thin waiter came up and asked what I would like to drink. I knew from my experience with Pete LaRoca that buying a drink was required, not optional. So this time I was ready. “I’ll have a Coke,” I said.

Believe it or not, the waiter said: ‘It’s two dollars for a Coke, and you can have it if you want. But for the same two dollars, you can get a real drink.” Here I was, under age, and not only was he serving me, he was encouraging me to get liquor!

Please understand, I'm from a lower-income Jewish background. My Mom was a struggling divorcée and I’m the middle of three boys. We lived in a small two-bedroom apartment and our Mom slept on a convertible couch in the living room. In our home, there was very little liquor. We had the sweet Manischewitz wine for Passover and one bottle of liqueur, I think peppermint schnapps, for guests.

The bottom line is, I knew nothing about liquor! But I understood that he was saying that I was wasting my money to pay $2 for a Coke. In those days a can or bottle of Coke at the store was 25 cents. So I thought quickly. I looked at the table across the little aisle to the right of me, and somebody was drinking something clear like water. I said, “What's that?” He said, “That's called a Tom Collins.” I said, “I'll have one of those.” He brought it and I hung on to it, “nursed” it, for the rest of the night.

So thanks to this waiter at the Vanguard, I got into the habit of buying a “real” drink whenever I went to the Vanguard or any other jazz club. Eventually I learned about more drink options, and I found out that there were sweet ones, so for a year or two I would order a Black Russian, because I love chocolate. I later learned that there was a White Russian and I liked that too, but not as much as the chocolatey one. Some years later, after college I think, I starting trying whiskey and other hard liquors, eventually ordering them straight so I could see what they really tasted like. But I never really liked the taste of liquor. I always bought one drink and nursed it all night. You save money that way too.

Many years later, in the fall of 1986, I met fellow pianist Don Friedman and we soon became good friends. I doubled on alto sax in those days and we did many gigs together. Sometimes we went out to hear music together and I noticed that he always ordered a seltzer with a twist of lime. The first time, I asked, “Is that all you’re getting”? And Don said, “Yeah, I don’t always feel like having a drink.” So, following Don’s lead, I learned to just order what I felt like having, which was usually not liquor. These days I’ll usually get a seltzer with a twist. And sometimes, people assume it’s because I have a problem with liquor. But my only problem with liquor is that I never liked it very much.

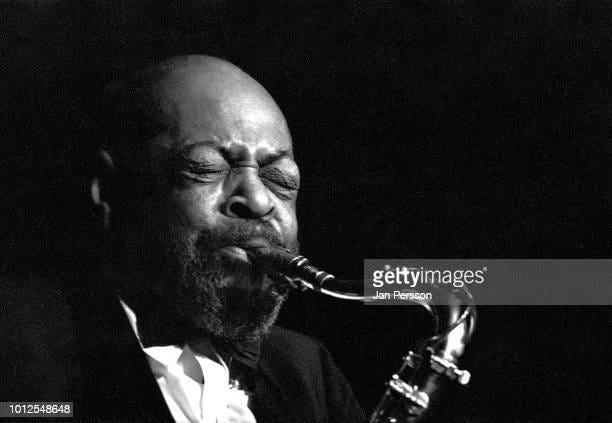

But, to get back to jazz, let’s not forget that the first time I ordered a drink, I was at the Village Vanguard to see the great Coleman Hawkins and his quartet in 1966. The club was far from packed—in fact I remember it being maybe a third full. Hawk was bald (some called him “the Bean,” referring to his head but also to his intelligence) and at that time he had a full beard. This is what he looked like:

His pianist around that time was often Barry Harris. But in my memory I see Tommy Flanagan, who I believe was on a break that year from touring with Ella Fitzgerald. The drummer was definitely Eddie Locke. The bassist was Major Holley. You couldn’t forget him, because he soloed by bowing and singing. But unlike his inspiration Slam Stewart, who sang in a falsetto, Holley sang in a low voice while bowing, which created a buzzy, resonant sound.

Hawkins was only 61 (he later passed away before his 65th birthday), but he was considered to be an “elder.” He was a brilliant artist and he still played really interesting lines. The only thing was, that night he often left pauses between lines as the rhythm section continued. Every once in a while during these pauses, he’d let out one laugh like this: “Ha!” He could have been laughing at something he played, and I wish I could say he was laughing because he was knocking himself out with his musical ideas. But honestly, it seemed more like the way someone laughs when they’re remembering something hurtful that somebody said earlier in the day. He seemed a little bitter, so who knows what was going on with him? But he was still brilliant and it was amazing to see him.

I was a shy kid. I sat by myself and didn’t talk to anybody. But I stayed all night—I wasn’t going to miss any of this! During one of the intermissions, trumpeter Roy Eldridge came by just to say hello to Hawk. I loved to see that, because I was, and am still, crazy about Roy’s playing, and I have written about it here. I wasn’t surprised, because I knew that they’d had had a long association. They’d been recording together since 1940 as well as performing together and touring with Jazz at the Philharmonic. Roy didn’t play that night—I did get to see him at the Half Note within the next year—but it was fun to see them together. They sat at a table in the middle of the club, and you could hear them laughing and enjoying each other’s company.

So that’s my story of seeing the great Coleman Hawkins, and of learning what to order to fulfill the minimum drink requirement at jazz clubs. I hope you enjoyed it.

All the best,

Lewis

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.