(Please use the Index to find the previous essays in this series. Just click on the word Playback at the top to get to the home page, then click on Index and look for Coltrane.)

As recently as Nov. 2018, the magazine Oxford American claimed that I have “speculated that in ‘Psalm’ Coltrane used his saxophone to articulate the words of the poem.” I’ve been saying this since 1978, and I don’t agree that it’s “speculation.” I think it’s fair to say that I am known for requiring very high standards of evidence. And even by my standards, Coltrane’s reading of the poem in “Psalm” is not speculation — it’s certainty, supported by tons of evidence. To cite only a few items:

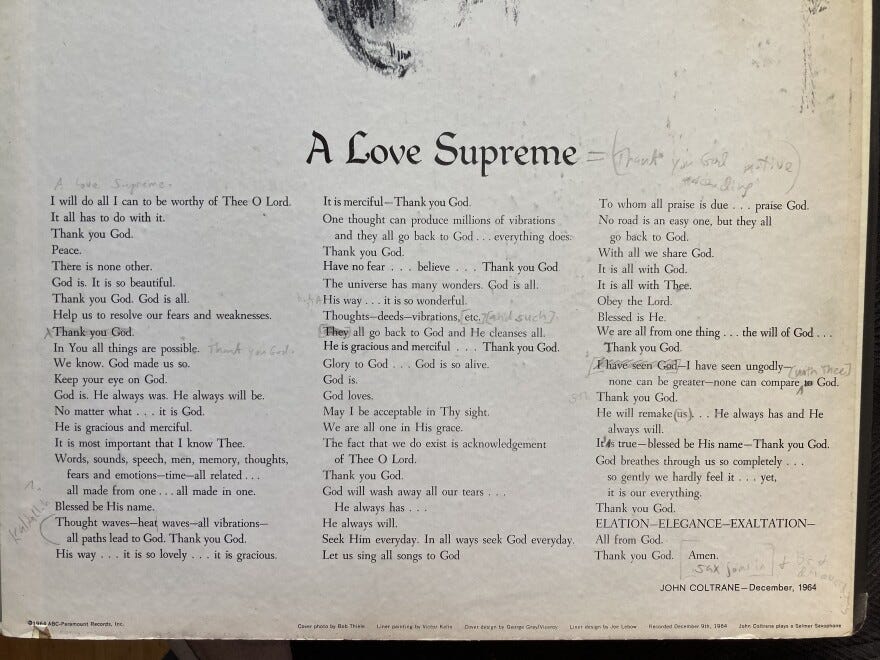

1. The poem in the liner notes, starting with the title “A Love Supreme,” matches up with the sax melody on “Psalm,” one syllable per note. Try reading it aloud with the recording, or watch the video linked below.

2. Another way of saying this is that the sax solo has the same number of syllables as the poem, up to the word “Amen” (which is given three syllables).

3. Every time the poem says “Thank you God,” Coltrane plays a three-note “Thank you God” motif, usually Eb, Eb, C. Let’s face it — this couldn’t happen by chance.

4. One of the iterations of “Thank you God” appears later on the recording than it does in the published poem. And there are a few other small differences. But the fact that you can hear this, and adjust one’s reading accordingly, is proof of how clearly one can hear the words in his playing.

4. Coltrane said it himself, although rather cryptically, in his liner note: “The fourth and last part is a musical narration of the theme, ‘A Love Supreme’ which is written in the context.” The mistake that people made here is to assume that he meant a musical theme. As we’ve all learned in school, literature has themes too, and in this case the supreme love for God is indeed the theme of the album, and the poem where Coltrane expressed that is indeed written in the “context”—that is, in the album notes.

5. As I noted in Part 2, we now have his sketches, where he not only writes out the words, but he also writes that the last part is a “musical recitation of prayer by horn…prayer entitled A Love Supreme,” and that the “Horn ends on Thank you God.” This is very specific evidence!

Interestingly, neither Tyner nor Jones knew that Coltrane was reciting his poem. Elvin was particularly surprised when I asked him about it. And when a French jazz journalist asked, “Do you think the text and the poem that you wrote aid in understanding the music?” Coltrane did not take the opportunity to tell the world (at least the French-reading world) about it. Instead, he replied (in my translation): “Not necessarily. I simply wanted to express what I felt; I had to write it.” It may seem surprising that John didn’t say “Of course! You’d better study my poem!” But all this is in accord with his low-key manner, not wanting to impose on anybody else, not even on his band members. Besides, he may have felt that he had already explained it in the album notes, not realizing that just about nobody “got” what he meant by a “musical narration of the theme.”

You can follow the performance with his written poem here (after an intro, “Psalm” begins at 0:30). It’s not perfectly synchronized, but it’s the best I’ve seen, and one can’t miss that Coltrane is “narrating” his poem:

Once you hear that Coltrane is “saying” the poem on his saxophone, it’s an amazing and profound experience. I’m sure you agree. I was the first to demonstrate with music notation that Coltrane reads the poem on his saxophone, in my 1979 talk that became an article and later was revised for my book, discussed in Part 1. Here’s a relevant page from my book:

However, I never claimed to be the first person who noticed this. I gave this talk again several times, and a handful of people in the audience said, “I already noticed that he was reading the poem,” and I believed them. After all, I myself had noticed it without reading about it. Also, some authors had mentioned it—just one sentence each, but enough to show that, clearly, they heard it. In 1965, Dutch critic Bert Vuijsje, in his review of the album, referred to Coltrane’s reading of the poem, as did Doug Pringle in the Canadian magazine Coda. New York-based critic Gary Giddins showed me an article he wrote in 1974, where he referred to it. And Dr. Cuthbert Simpkins, in his 1975 Coltrane biography (p.180), wrote "In the last section of the composition, he plays the words of a poem entitled ‘A Love Supreme,’ which he wrote. It was also placed inside the album cover.” I did not know any of these writings until many years later, but they all deserve recognition.

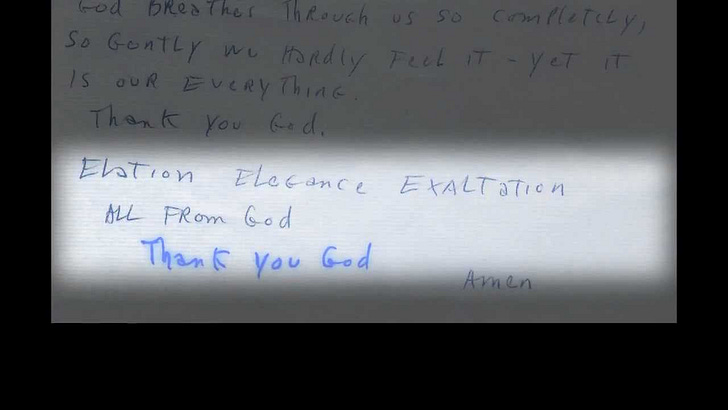

As I mentioned, there are a few small differences between the poem as printed in the album and as “read” by Coltrane on the saxophone. I noticed this back in 1978 and wrote them in pencil on my personal copy of the LP, along with a few other notes which you can see here:

What accounts for these differences? First of all, let’s be aware that the performance on the album matches his final handwritten version of the poem, more closely than it fits what’s printed on the album. We looked in Part 6 at previous drafts of the poem, including that final four-page version. But even so, there are a few instances where Coltrane clearly plays “Thank you God” that do not appear in the handwritten version. Also, Coltrane’s own notes said, “Horn ends on Thank you God.” But on the recording he doesn’t end there—he follows that with “Amen,” expressed in three notes. It’s the only word that has added syllables. (After the words end there is a little flourish, and the overdubbing that we discussed in Part 3.)

But why are there slight differences between what he wrote and what he recorded on the saxophone? Well, first of all, even though some people have said that Coltrane must have had the written poem in front of him, I don’t think we can assume that. Nobody has ever mentioned seeing him use a music stand at this session, and photographer Chuck Stewart was not present. (He attended the second day, when there were music stands for the added musicians, as we saw.) Having worked on the poem for perhaps a few months, it’s certainly possible that Coltrane could have memorized it, and if so, it’s equally possible that he misremembered, or spontaneously changed, just a few phrases. Given Trane’s laid-back attitude about such things, it is also no surprise that he didn’t try to edit the poem to exactly match the recording, before submitting it to be printed in the notes.

It’s also in keeping with his approach that on the live version of “Psalm” from France in 1965, he didn’t try to match what he did in the studio word for word. Right from the start, he plays freely, using the studio version simply as an outline. For example, after 0:14 he repeats the last notes of “It all has to do with it.” At about a minute in, he is already up in the high register. And from around 1:30 on, he plays a rapid free improvisation, ignoring the poem, and referring only briefly here and there to the style of the studio recitation — for example, the passage from 5:45 until 6:35 is somewhat similar to the studio version. But let’s not lose sight of the main event: this is powerful, moving music. Here it is:

At the very end, he plays “Amen,” then at 7:40 plays the high C heard on the album, with the same strained tone. This confirms, if we needed confirmation, that it was he who overdubbed the second saxophone at the end of the studio version.

At a nightclub in Seattle, as on the French concert, Coltrane doesn’t “recite” the poem as he did on the studio recording, but maintains the style and refers at points to the words. With Elvin using mallets, and two bassists bowing, John blows the words “Thank you God” at 1:33, 2:20 (echoed here by the alto sax), and at 4:56. At 3:08 he latches onto the Eb and C of “Thank you God” and fiercely develops it for a while. From 4:08 onward, he sounds like he’s expressing other words from the poem. He plays very high around 1:00 (reaching to an F—his G—a ninth above the standard top note) and again starting around 3:47. Compared with the studio version, Tyner’s accompaniment is very active, and moves into higher registers. Listen to him at any of these moments, for example starting at 4:08. Coltrane concludes with “Amen” at 5:13. (We’ll talk about what happens after that in a later post.) Please listen:

I mentioned last time that it is possible that Coltrane had words in mind for the beginning of his solo on “Acknowledgement.” In the next essay of this series, we’ll return to that movement. After all, there are more surviving takes of that piece than of any other part of the suite, so there’s a lot to listen to! Meanwhile, in separate essays, I will explore other pieces where Coltrane had texts in mind, and what we know about them. Coming soon!

All the best,

Lewis

Although I listened to the album many, many times since getting it as a high school saxophonist in the early 70s, the literal syllabic "recitation" didn't occur to me until you pointed it out. I read your dissertation before your book came out, and was 100% convinced by your explanation. I feel it's obvious when listening, especially confirmed by the "Thank you, God" phrases. (I believe I read the Simpkins book around the same time in the late 1980s, but it must have been just after reading your dissertation. I taught a couple of courses on Coltrane at Tufts and used and cited your work extensively, along with the other books.) I've been intrigued since then by a Coltrane quote I can't place at the moment, but I'm sure you're aware of it: paraphrasing "Everything I play is a prayer now." Something like that. Besides the motive of "The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost" from _Meditations_, I can't cite any proof, but I'm intrigued and I look forward to your next posts for more info. By the way, anyone who finds this strange is probably forgetting that many jazz saxophonists have the lyrics in mind when playing ballads -- even me, to the extent I can remember them, and certainly their syllabic content, poetic rhythm, and contour. If you know standards as done by singers, the connection between melodic phrasing and embellishment and words is an essential element of jazz playing. And with his family connection to preaching, hymns, etc., this seems to be a very natural development.

It’s great to see all the documentation you’ve assembled about the poem and the music. But it amazes me that anyone would doubt the connection between them. I saw it when I was back in high school, many (fifty?) moons ago, listening and looking at the album gatefold. I'd say it was unmissable.