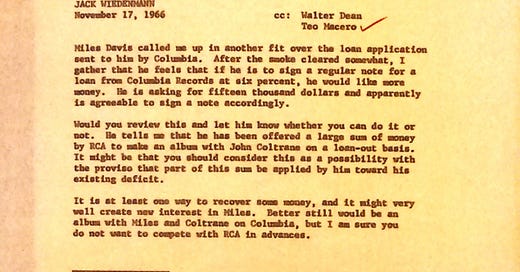

I’m sure that my headline has already blown your mind! Well, in Part 1 of this series, I told you about a 1959 proposal for Coltrane to record an album of Monk tunes. Today let’s look at another project that never happened. Let’s start with this letter, from November 17, 1966:

Townsend was the Columbia Records producer who supervised Kind of Blue, among many other albums. (Remember, IJT:md means dictated by Townsend but typed by someone else. In this case the typist’s initials appear to be MD like Miles’s!) Jack Wiedenmann had produced pop albums by Ray Conniff and others, but he was better known as a high-ranking executive at Columbia, and later at other labels. His name is in upper case to show that the letter is addressed to him—the two people on the right side are cc’d. Walter Dean had joined Columbia in 1956 on the business side, and had just been promoted, about a month or two before this letter was written, to serve as Administrative Vice President of CBS Records (CBS was the overall company that included Columbia Records). And Teo Macero was of course the producer who worked with Miles on every Columbia album after Kind of Blue (and on some aspects of the release of that album, after it was recorded).

There is no greeting—no ”Dear …” The letter starts right in. And I have to laugh at the first sentence, which refers to “another fit” by Miles Davis. Miles was in the habit of telephoning people at Columbia, and by Townsend referring to Miles this way, it’s clear that they all knew him to be a “difficult” person. Miles had asked for a loan, and apparently he was angry that they were only willing to give him a loan if he signed a formal agreement (called a promissory note, or simply a “note”) at 6 percent interest.

Why were they even discussing this? Artists like Miles were already entitled to an advance with every album. But if one wanted additional money, instead of going to a bank, one could ask for a loan. Townsend says that “after the smoke cleared,” that is, after Miles calmed down, he realized that Miles actually agreed to the terms, but was saying that as long as he was taking out a loan, he might as well get more money ($15,000 instead of a lesser amount).

Now here’s where it really gets interesting. Miles had told Townsend that RCA had offered him a lot of money if Columbia would loan him out to make an album with Coltrane! (I wonder who was behind that offer? Producer George Avakian had left RCA around 1964, but he was still doing freelance projects, and was still friendly with both Miles and Trane. Could he have been involved?) This is of interest to Townsend mainly for financial reasons—he doesn’t say anything about the exciting artistic potential of this! He wants to put it into their loan agreement, something like this: “When you get your money from RCA, you agree to pay back to Columbia a certain amount”—maybe $5,000—”of the money that we will loan to you.” He also notes that it would be better for them if they could do the Miles and Trane reunion on Columbia, but RCA has more money and they would not be able to compete with RCA’s offers.

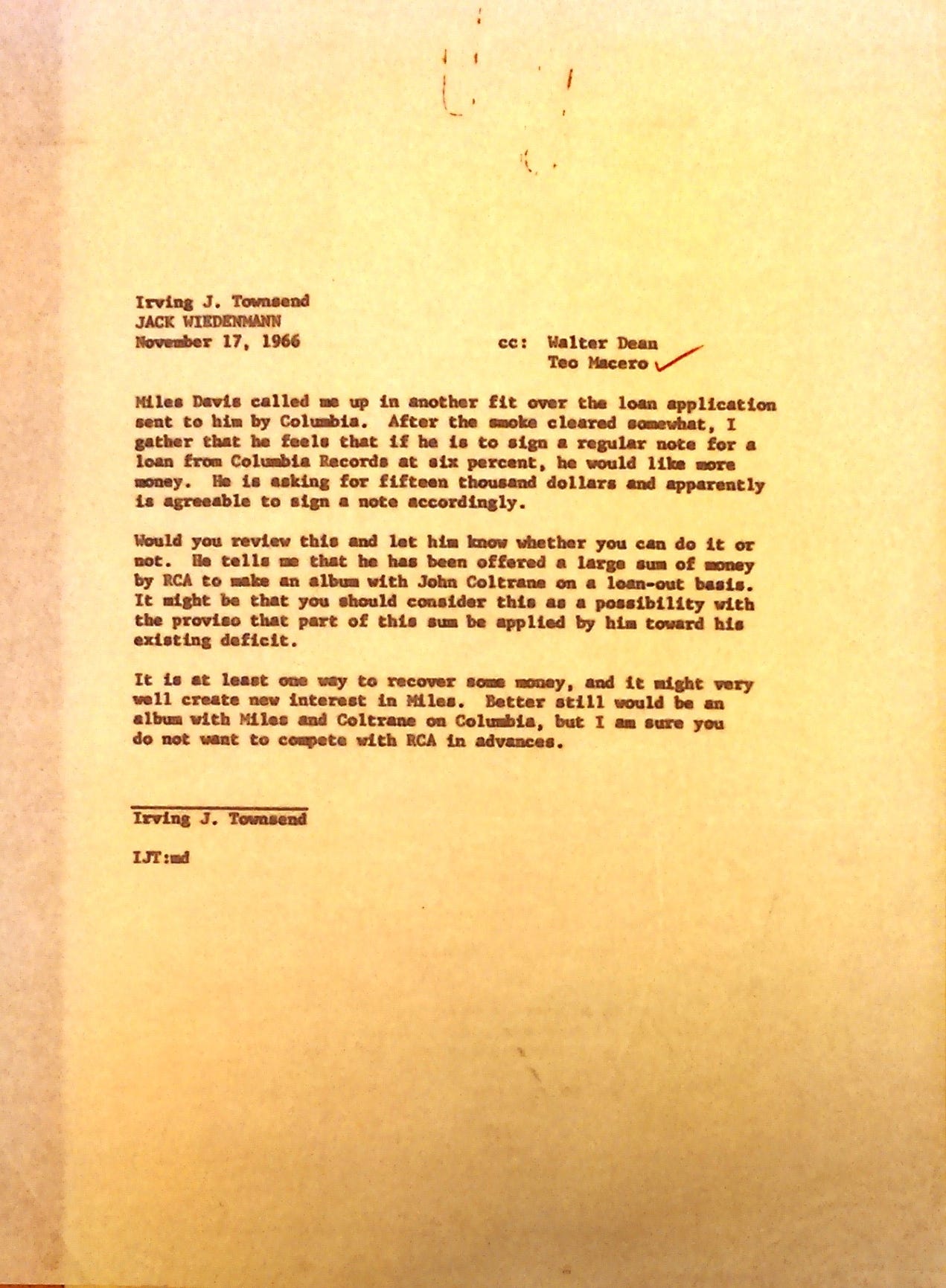

Interesting!! OK, let’s move forward a few months to March, 1967:

This letter is from Walter Dean to Clive Davis. Of course Davis, who is now 91, is a well-known person in the music business. He was then Vice President and General Manager of Columbia Records (he would be appointed President in the summer of 1967). Dick Asher was Vice-President of Business Affairs, Bill Gallagher was head of marketing, and you already know Macero and Townsend.

Miles had phoned the President of Columbia, the famous Goddard Lieberson. Lieberson then contacted Clive, and Clive had asked Dean to call Miles. Dean’s letter says that Miles wanted to know why Columbia wouldn’t give him “a release.” That usually referred to being temporarily “released” from your contract in order to record for another label. Based on the rest of this letter, it appears that the offer from RCA was no longer happening, but there was now another plan:

Dean said there was no reason for a release, and apparently they had decided to try Townsend’s idea of keeping Miles on Columbia by offering generous advances. But the policy was not to pay the advance until the album was recorded (but it didn’t have to be edited and released). Miles wanted more money, and he wanted half of it before he even went into the recording studio. When Dean said he couldn’t do that, Miles hung up on him!

But this leads to some amazing news: Apparently there had already been a discussion about Miles and Coltrane doing one album together for Impulse and one for Columbia! This kind of arrangement was common, because by “trading” artists in this way, neither label had to pay the other for the release. It was an even exchange when both artists were equally popular, as in this case.

Harold Lovett (I think that’s the correct spelling, but you will often see it with an “e” on the end) was a Black lawyer who also served as Miles’s manager from about 1955 through the early 1970s. He not only handled legal issues, but negotiated with the record companies for Miles, handled details of gigs, and so on. He worked with a number of other prominent Black musicians as well.

Lovett said that Miles had spoken with Townsend about this idea of two Miles and Trane albums, and he was under the impression that it was already approved. But Dean explained that couldn’t be correct. It couldn’t have been approved by Townsend (or Macero) acting alone, because, the way their business worked, Gallagher had to make a decision. Dean added that the current suggestion of a $15,000 advance from Columbia for Miles was too high. Lovett suggested that maybe Coltrane could lower his price, and that would make the Columbia album affordable. Dean apparently thought that might work, so he advised Lovett to talk with Gallagher.

That’s all I have found in the files about this. I don’t have the discussions about the Impulse album that was also proposed. And what would the music have been like? There is no doubt that Miles and Trane had already talked, and had agreed about some musical ideas for these albums—if not, the plans would never have gotten this far. In fact, saxophonist Gene Ghee says that at the end of 1966, Coltrane specifically told him about the planned recording (listen to Gene at 7:27 in this interview). But you can be absolutely certain that they were not going to play “Bye, Bye, Blackbird”! And Miles said more than once that he didn’t respect many “free jazz” players.

But even though Coltrane’s music in 1966 and 1967 was indeed free, it had a powerful basis in modal playing—for example, think about the gorgeous “Peace On Earth,” as well as “Ogunde,” and “Venus.” And Davis was clearly interested in playing freely himself, even if he didn’t respect all musicians who did so. After all, by the time the above letters were written, he had released some very “open” pieces such as “Agitation” and “Orbits,” both written by Wayne Shorter. On “Orbits,” as Keith Waters has pointed out in his perceptive analytical book on the Davis Quintet of the 1960s, the musicians solo in time, with Ron Carter’s walking bass, but they are soloing “free,” not following a pre-determined progression of changing chords. (Some musicians like to call this “playing time, no changes.”) And in May 1967, Davis would record some more of these experimental pieces written by his sidepersons, for what became the album Sorcerer. And even though Coltrane was no longer using a walking bass for his own music, he might have been open to using it with Miles. Besides, when Wayne or Herbie Hancock soloed, the group often got away from the walking beat, especially in “live” performances documented on recordings. So Coltrane could have done that during his solos. Essentially he could have taken over Shorter’s role in Miles’s group. In fact, I would guess that the Columbia album would have used Miles's rhythm section, and the Impulse album would have used Trane's band. (But now I'm wondering, would it have been his previous quartet with McCoy and Elvin, or his current free group with Alice Coltrane and Rashied Ali? It’s hard to imagine Miles with the current group, but it’s possible.)

So there would have been plenty of ground for Trane and Miles to meet musically. But it appears from these letters that the negotiations were moving along very slowly—too slowly, as it turned out. Because, as I don’t have to tell you, Coltrane began feeling ill by late May, and he died from advanced liver cancer on July 17, 1967. He was only 40, and Miles was shocked when he heard the news, as was everybody else.

Very sad, in so many ways.

All the best,

Lewis

As it happens, I've been reading Will Friedwald's Sinatra bio, and last night came to his discussion of the wonderful recordings he had made with Bobby Hackett in 1945. Friedwald goes on to relate a casual conversation held years later in which Ruby Braff says to Sinatra, "Weren't you smart to make those great records with Bobby? I always wondered why you didn't do more of them." Friedwald, quoting Braff, says "at this point, Sinatra got a kind of faraway reflective look in his eye, and told Braff, 'You know, you always think there'll be time to all the things you want to do, but somehow there never is.' "

I recall—and would have to look it up—that Miles was none too appreciative of McCoy’s playing in Miles’ autobiography. Herbie Hancock may have been more adaptable to Trane’s music. As for Miles with Alice, Garrison, and Rashied—the mind boggles at the thought!