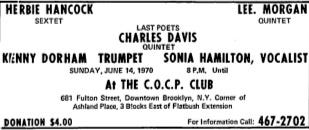

This was one of the greatest nights of music I ever attended:

Yes, all of those groups performed in one night—for $4 !! It was the only time I saw Dorham, Morgan, or The Last Poets.

How did I hear about this event? At that time an organization called Jazz Interactions compiled a weekly listing of all the jazz in New York City. You could subscribe to the printed listing, or you could call for free to hear a recording of someone reading all the listings. (That ended years ago, and today the most complete listings of jazz in N.Y.C. are in this free PDF publication, which comes out at the beginning of every month.)

On the recorded phone line in June 1970, they said that all of these groups would be performing at “The Black Social Club of Brooklyn.” I never did find out what the official title, C.O.C.P., stood for. But my former graduate student Jeff McMillan, author of the Lee Morgan bio, was told by a friend of Morgan that it meant Community Ownership for Community Power.

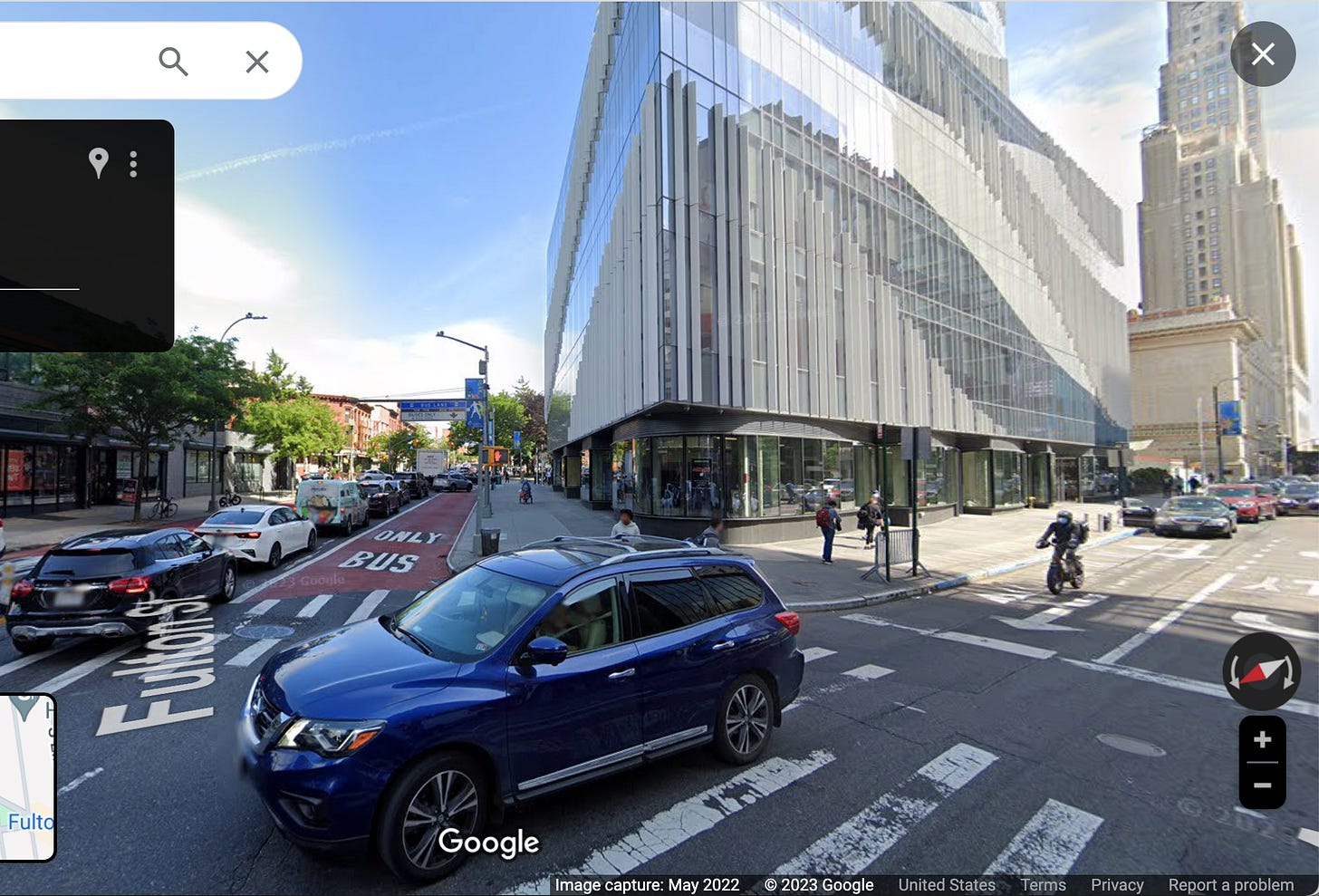

I lived in the Bronx, far away, so on Sunday, June 14, 1970, I made my way there on the subway. It was a low building at 681 Fulton Street on the corner of Ashland St in Brooklyn. I paid my $4 at the box office and went in. It was a kind of meeting hall with about 10 or 15 rows of wooden chairs and a stage. I sat about three rows back, on the middle aisle. Soon The Last Poets came on stage, three Black men and a conga drummer. (I do not remember them performing with the excellent saxophonist Charles Davis, as suggested in the ad above. But I vaguely think that he may have performed one or two numbers before they began.) I’m pretty sure that Felipe Luciano was no longer in the group—in any case, I don’t remember seeing him.

As you may know, The Last Poets are now considered predecessors of hip-hop, with their rhythmic renditions of original and outspoken poetry. They were impeccably rehearsed, with lines passed quickly among them and sometimes recited in unison. They spoke of race and racism, and I found them to be very exciting and truthful. I remember thinking that they were brilliant, and that their critiques of white people were tough but fair, but that they didn’t spare Black people either. They held everyone to a high standard.

I specifically remember some of the pieces they performed. They presented two poems that appeared on their first album—“N..s are Scared of Revolution,” and “When the Revolution Comes.” And from their second album, they performed the title poem “This is Madness!,” as well as “Related to What,” and this one, “The White Man’s Got a God Complex”:

Next was Kenny Dorham. I don’t remember who else was in his group, except that Billy Higgins was on drums. Dorham announced that Billy had just bought drumsticks that were hollow and had beads inside and that he might do something special with them. Sure enough, during a drum solo, Billy held the sticks up in the air and just rattled them for a while—a very memorable moment. There was definitely a piano and bass, and maybe a saxophonist, but I’d rather not take any wild guesses as to who they might have been. As you’ll see in a separate essay on Dorham, he was not successful enough to support a steady band, so his group’s personnel was always changing.

About the singer Sonia Hamilton who is listed in the ad: I vaguely recall her hosting the evening and introducing the bands, but I don’t remember her performing.

Next was Lee Morgan’s quintet. This was a regular working band that is well documented, with Bennie Maupin (sax), Harold Mabern (piano), Jymie Merritt (bass), and Mickey Roker (drums). This was the band that was recorded Live at the Lighthouse a month later. Roker, who I loved on Duke Pearson’s Album Wahoo, was a highlight for me. I wished they had played Lee’s tune “The Sidewinder,” but, as is evident in the Lighthouse boxed set, he rarely played that tune then. His set was entirely composed of originals that were unfamiliar to me, composed by various members of the band. You can hear samples here.

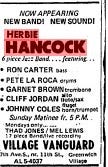

Finally, Herbie Hancock came on with his sextet. That was the first time I saw him. I had seen Miles Davis the year before, but by that time Chick Corea had replaced Herbie. The sextet was the group that Herbie organized after leaving Miles in 1968. Here you can see an early version of the personnel:

By March, 1970, this was the personnel:

And when I saw the group in June, Joe Henderson was not there. I believe it was this personnel, which would mean that Maupin played in two bands that night—and I kind of recall that he did: Eddie Henderson (tpt), Julian Priester (tbone), Bennie Maupin (sax), Herbie Hancock (keybds), Buster Williams (bass), Billy Hart (dms). (I saw them again in the Fall of 1973 at The Lion’s Share in Marin County north of San Francisco. That time Patrick Gleeson was added on synthesizer.)

This was difficult music. They definitely played “Wandering Spitit Song,” a long piece which you can hear here, and I believe they also played “You'll Know When You Get There.”

What an evening! The performance space is long gone. There is still a phone number listed online, but it doesn’t work. From Google Maps, here is what that corner looks like today:

I hope you enjoyed these memories.

All the best,

Lewis

It was a dream reading this

Maybe when I die & go to heaven..

Thanks for posting, Lewis!

In 1970, Hancock was recording for Warner Brothers Records- the recorded versions of "You'll Know When You Get There" and "Wandering Spirit Song" were for that label. (They appear on the excellent 2CD Hancock anthology "Mwandishi", a favorite of mine).