Miles Davis Did Not Exactly "Steal" Tunes, 1: Record Labels, Publishers, and "Solar";Award Winner

(This article won the national 2024 ASCAP Virgil Thomson Award for Outstanding Music Criticism in the pop music field.)

In my first post on Miles, I wrote: Strangely, Miles has become the artist that people “love to hate.” Under articles about him on the internet, there are often readers’ comments saying very insulting things, even cursing him out in crude childish terms. (If you don’t believe me, or if you want to waste your time reading foolish things, you can, for example, read the comments on this page. I often wonder if people who upload videos to Youtube know that they can delete rude and unwanted comments.) My research tends to support a much more sympathetic view of him. For some examples, you can scroll through to my previous posts showing his warmth toward his musicians, showing that he was not responsible for losing his voice (here is Part 1—there are two installments so far), and so on. And almost all of the musicians who actually worked with Davis speak positively about him.

In the past, whenever I have said online that Miles did not steal tunes, many people wrote to me hysterically, almost yelling, “But everybody knows that Miles did steal tunes!” I’m sorry, but that is absolutely not what “everybody knows.” That is not even what you, my dear reader, know. What you know is this, and only this:

A few tunes that were not written by Miles Davis have his name listed as the composer.

That is all you know. Nothing more than that. Am I right? Do you have some evidence that Miles himself put his name on those tunes? Have you done some research on this? The usual explanation is that he must have handed in a leadsheet of each piece with his name listed as composer. As I will show, that is wrong.

And it’s not just word of mouth that says he “stole” tunes. You will often see books and articles saying that Miles did this. It amazes me that people who write about jazz often know nothing, and I do mean absolutely nothing, about the music business. In order to discuss this, one needs to know how things worked in the recording industry. (Of course in today’s era of streaming, many things have changed. However, a surprising amount of the terminology is the same, even though it is often applied differently.)

So please calm down, keep an open mind, and read closely:

After a recording session, but before a recording is packaged and released, it is somebody’s job at the recording company, aka the label, to research and file a copyright for every track. On the released album, the composer is usually listed in parentheses after each song title. When the album is available in stores, and people start buying it, and money is being made, there are several kinds of royalties that get paid out of that money:

The leader of the group gets an artist royalty on every album sold. The exact amount is determined by his or her contract. Sidepersons do not collect royalties—they get a flat payment for completing a “work for hire.” (And please, let’s not cry about the fact that the musicians on Kind of Blue other than Miles did not get royalties. They knew that was the deal, and that still is the way things work. I have recorded as a pianist on 37 albums to date, mostly as a sideperson, and although I do my best to make each piece sound its best, I am constantly aware that I am performing in support of the leader’s or co-leaders’ vision. I am following their instructions. They should, and do, get the most credit.)

I should mention, however, an additional payment to sidepersons: I mentioned in a post about a proposed Coltrane recording that the musicians’ union (the N.Y.C. Local 802 of the A.F.M) was involved in professional recordings—paperwork was filed through the union, payments were made by the record company to the union, and the musicians went to the union to pick up their checks. Sidepersons did get a small bonus based on sales during the first five years of each recording’s existence. (Thank you to Richard Weissman for reminding me about this.)

Back to royalties: For every track on each album that is sold, there is a “mechanical royalty,” a standardized payment, based on the length of the track. (In those days it was 2 cents per song per album sold.) That royalty is split between the composer (or composers), and the publisher. In practice, it is paid to the publisher of each composition on the album, and it is each publisher’s job to pay 50% of that fee to the composer.

There are other royalties that are split between composer and publisher: Performance royalties for radio or television airplay are collected by an organization that the composer or publisher belongs to, most often BMI or ASCAP, and sometimes SESAC. And royalties from sheet music sales, also shared between composer and publisher, at one time were a much bigger part of the music business than they are today.

I should note, however, that the “publisher” refers to the entity that owns or administers the copyright of the piece, and handles business relating to that copyright. Most people think of “publishing” as having music printed out and sold in stores. That is not necessary in this case, although as I’ve just noted, if it is published in that form (such as a Chick Corea songbook, anything like that), royalties are collected.

One more type of royalty: Whenever a recording is synchronized to a film or TV show (or today, a video), a “synch royalty” is paid. These fees are negotiated on a case-by-case basis and shared between all partes— the label and the recording artist, as well as the composer and publisher. Although “synch licensing deals” are infrequent, they can be, as you might imagine, some of the largest payments that a musician will ever earn.

The composers of the tunes on an album are very often people like Monk, Ellington, or Gershwin, not the performers on the album. But if the composer is indeed a performer on the album, but is not the leader, then he or she gets the flat payment for being a sideperson, plus the performance royalties for the composition. A famous example of that is “Take Five.” For the Brubeck album Time Out, Desmond was a sideperson, so he did not directly receive any artist royalties for sales of the album after it was released in December 1959. But Desmond’s was a special case—he had a private agreement that Brubeck would share 20% of all profits with him. And when his song “Take Five” became one of the biggest jazz hits ever, possibly the very biggest, Desmond did very well due to his mechanical, performance, and sheet music royalties. Since his death in 1977, his estate has also collected synch royalties for its use in soundtracks.

Now, as you’ve just learned, if a song has a publisher, there are a several types of royalties that will be split between the composer and the publisher, 50% to each. In the 1950s, a number of jazz musicians began to realize that if they were their own publisher, it meant more money for them. Saxophonist and composer Gigi Gryce was one of the first to set up his own publishing for just this reason—to keep 100% of these royalties instead of 50%. As the late pianist-composer Horace Silver told Noal Cohen and Michael Fitzgerald for their book on Gryce: “Gigi was responsible for turning me on to music publishing.”

But most musicians, including Miles, did not handle their own publishing business. And a number of recording companies, such as Savoy, Prestige and Blue Note, had their own publishing division. (Again, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you could buy the sheet music in a store. It means that they owned the copyright and handled the publishing business.) Although the artist’s contract did not usually require him to use the label’s publishing services, there was definite pressure to do so. There was enough pressure that some musicians to this day tell me that if they wanted their album released on a certain label, it appeared that they would have to assign their copyrights to the label’s publishing branch.

As Bob Weinstock, founder of Prestige Records, told the authors of the Gryce biography just mentioned, if the musicians didn’t already have a publishing company, he would explain to them why they needed to let Prestige handle their compositions. He said, “I explained to them that if they did publish with me, that they would get money from all over the world because my company was respected and people requested licenses from everywhere.” And, to be fair, there was some truth to that. As with many situations, such as payments to agents, some musicians felt that it was worth letting the label have some of the income, because they brought in much more business. As I like to say, “Half of something is better than all of nothing.”

Now, here is where you need to really pay attention, please:

Jazz musicians often bring pieces to a recording session that have no known composer. (Often, they are untitled as well, which I’ll discuss in other posts.) When preparing the album for release, the record label, and the person in charge of the composer credits and copyrights, has to make some decisions. Here’s an example:

It’s 1954, and Miles Davis is under contract to Prestige Records. At a recording session (with, incidentally, Silver on piano), Miles brings in a previously unknown piece based somewhat on “How High the Moon” and says that he learned it by ear from other musicians and doesn’t know who wrote it. (That appears to be true, as we’ll see next time.) In preparing the album for release, the people at Prestige Records have to make some decisions:

Even if Miles said, “I don’t know who wrote this, but it was not me,” the label would still need to give someone the credit. With no clues to go on, they could conduct an intensive research process to discover the composer. It wouldn’t be easy, but if they were successful, they would discover that it was written by guitarist Chuck Wayne (1923-1997). If they credit the piece as a Chuck Wayne composition, they would have to contact Wayne or his publisher. Prestige would pay some money “up front” (that is, before the album comes out), and would continue to pay mechanical royalties for the song once the album is selling. (For performance and sheet music royalties, people would usually contact Wayne or his publisher directly.) Prestige would of course get royalties from the sales of the album, but if the song becomes a hit, and other artists record it for other labels, Prestige would get nothing from those, but Wayne and his publisher would profit.

On the other hand: If they credit it to Miles, who is currently under contract to Prestige, they will handle the publishing. When he signed his contract with Prestige, Miles had already agreed that they would serve as the publisher for any piece where he was the listed composer. So Prestige would keep half of the mechanical, performance, and sheet music royalties. As for the other half, they will pay Miles an advance payment, usually $50, and it becomes a simple bookkeeping matter to keep track of what is owed to Miles once his royalties exceed $50. (And as I’m sure you know, many musicians over the years have suspected that they were not getting their royalties, but there was no way to check.) If the song becomes a hit, and numerous other artists record it, even for other labels, Prestige will indeed benefit, and will share the income from that with Miles, half and half.

Silver, in the same interview cited above, clearly spelled out why it was an advantage to the record company to own the publishing rights to his music. Initially he was with Mills Music, which had published Duke Ellington and others:

[I]f I had my tunes with Mills Music, and I did something for Blue Note, they would have to pay Mills Music 100% royalty, you know. And then Mills Music would take 50% and give me 50%. But now, if Blue Note started their own publishing, and they get me to put my tunes with them, that means they save 50% because they pay themselves 50%. They only pay me 50%.

IN SHORT, here is the bottom line:

When a piece is being recorded for the very first time, and there is some room for legitimate debate as to who composed it, it is always to the financial advantage of the record label to say that it was composed by an artist who is under contract to them. If they knew the composer, they would not blatantly lie and credit it to their artist, but if there was reasonable uncertainty, they would say, “Let’s give the composer credit to our artist.”

Put slightly differently, from the musician’s side, there is always a certain amount of pressure on an artist who has a recording contract, to record pieces that he or she has composed. In fact, it was not unusual for a producer to say to an artist, “At your next recording, I hope you’ll bring some things that you wrote, and that you’ll let us publish them for you.” And, of course, this was financially beneficial to the artist. Very few musicians would say “The composer is unknown, but please, please do not give the credit, and royalties, to me.”

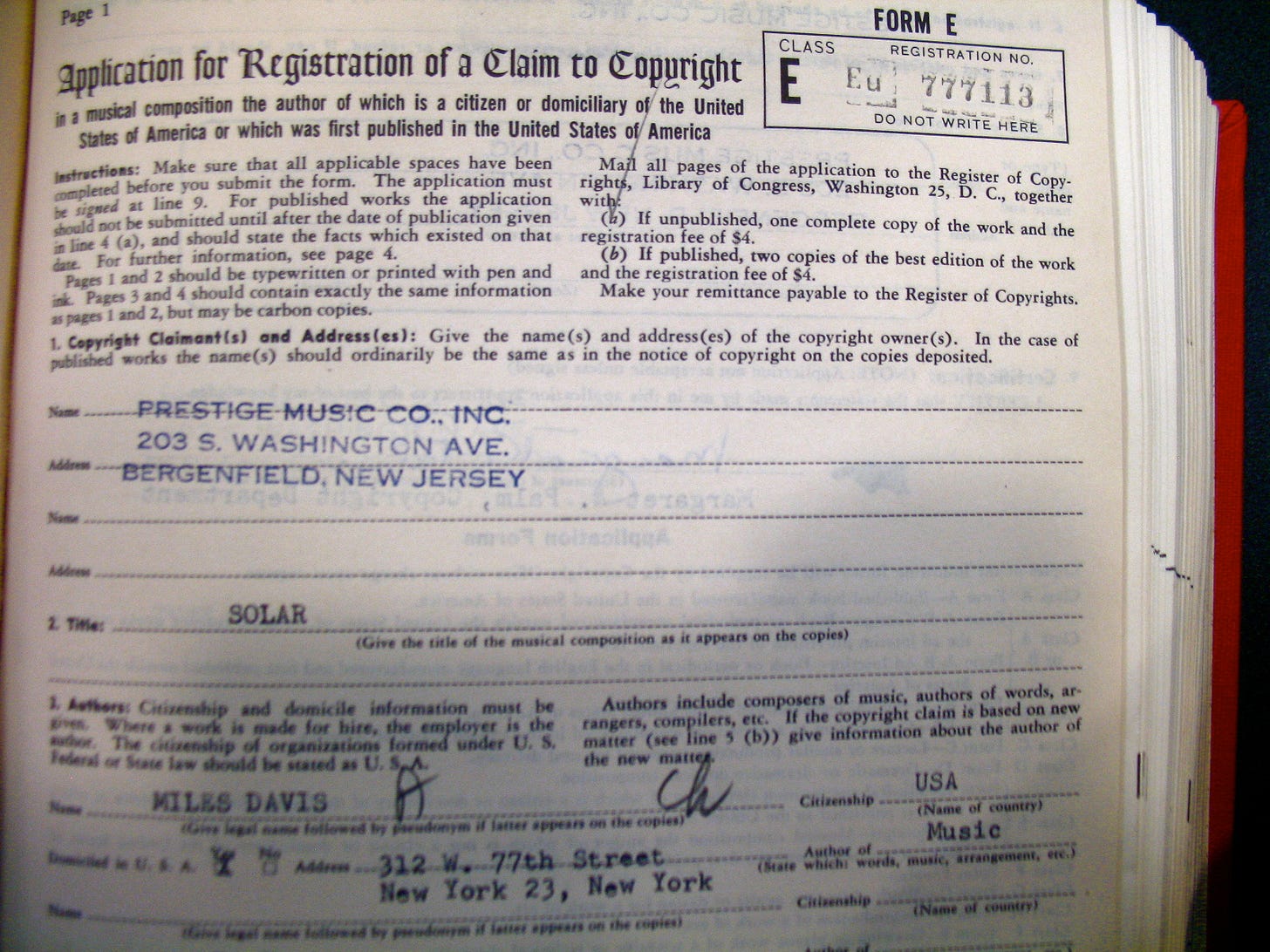

Now, since you’ve followed me this far, let’s look at the copyright information for that song, the one that is based on “How High The Moon.” As you probably know, it’s called “Solar.” Who owns the copyright? Let’s see:

HELLO!! Are you looking? Prestige Records owns the copyright, not Miles Davis. Miles, the person whom you love to call a thief, is listed as the composer. And it was Prestige who sent in the form claiming that he wrote it, not Miles himself.

The copyright registration above was filed on August 8, 1963, which is a different matter: According to U.S.A. law, copyright exists from the moment a work is created, without registering the copyright at the Library of Congress. Registration offers additional legal protections, but it’s a bit of a hassle and requires a fee, and the fee is lower for a group of works. So, often companies and individuals will wait until they have a pile of them and then send them all in at once. (Many of Coltrane’s compositions were first registered in the 1970s, even though he had died in 1967!)

And another side note—At the top of the page, the form asks if the piece is published. Here they are referring not simply to having a publisher assigned, but as to whether the piece has actually been printed and is for sale. That’s why it says that if it has been published you should attach “two copies of the best edition.”

There is much more to this complicated story, so I will be presenting it in several more installments. I will address the following questions, and more:

How did Miles learn “Solar”? What is the evidence?

How does Miles’s version differ from Chuck Wayne’s original?

How is “Solar” based on “How High the Moon”?

Where did the name “Solar” come from?

What about Coltrane, Rollins, Parker? Did any pieces get wrongly credited to them? If so, do you want to say that they “stole” tunes too?!?

Were there instances when Miles explicitly demanded a composer credit, when one might say that he was not justified?

What are some other ways that pieces get credited to the wrong composer?

Also, I will go through many of the specific pieces in question, tune by tune. I will specify in each case what role Miles himself played, if any, in getting the piece credited to him.

BOTTOM LINE:

I am NOT saying that Miles was always totally innocent. I AM saying that it is not a simple matter of him “stealing” tunes. Instead, it is a question of how the music business is structured.

MUCH MORE TO COME!

All the best,

Lewis

P.S. For musicians: As noted above, half of your performance royalties from BMI or ASCAP will go to your publisher. But every online site that I’ve seen says that if you do not list a publisher, you will lose that half of the money. That is false, false false! Ask BMI, ASCAP or whatever organization you belong to. They will tell you that if you don’t list a publisher, all the money goes to the composer, period. BMI refers to this as getting 200%, meaning that you get 100% of the composer’s royalty plus 100% of the publisher’s royalty. They state: “You need not affiliate a publishing entity in order to receive publishing shares, as we pay all royalties (writer and publisher) to the composer on any self-published works…Please note that while composer affiliation is free, there is a one-time fee to affiliate a publishing company with BMI.”

P.P.S. I thank long-time jazz record producer Michael Cuscuna for looking over an early draft of the section about types of royalties. But any errors are mine alone, of course.

Hi Lewis, fantastic insights as always!

Why does Miles take the brunt of these criticisms? I recently heard Jay Leno say in an interview “what do you do in football? You tackle the guy holding the ball.“

I hope this illuminates for readers and musicians alike the complexity of navigating the music industry and how conditions on the ground affect and influence an artist.

Not that I feel Miles needs any of our sympathy, or somebody to apologize for him, but the reason he’s such a compelling figure is that he always has so much wonderful music and artistry to offer us. Your step-by-step insights on the logistics of putting out a record are helpful.

I have dim memories of Bill Evans composing pieces for which Miles is listed as the composer.