Miles Davis: "Nardis," Part 3 of 3—A Possible Inspiration +Bonus

(Paying Subscribers, four unusual and entertaining recordings are at the bottom for you.)

In Part 1 and Part 2, we’ve spent a lot of time analyzing the many reasons that we know Miles Davis wrote “Nardis.” All parties always maintained that Miles wrote it, including Miles himself and pianist Bill Evans, who played on the first recording of the song and made a specialty of playing it. The next step would be to try and learn how Miles got the idea for this excellent and unusual tune. For example, we might look for songs that use the same scale, which would almost certainly be from outside the jazz world.

Harmonica virtuoso and pianist Howard Levy recently suggested that I look at the song “Misirlou.” He pointed me to his video about the scales of “Nardis,” where he shows how to play “Nardis” on the diatonic harmonica, and ends with a discussion of “Misirlou.” That is such an interesting point that I’ve decided to add this third post about it. As you’ll see, “Misirlou” may have inspired Miles to write “Nardis,” even though the two songs are quite different. And in any case, this is an opportunity to investigate the fascinating history of “Misirlou.”

It is usually said that “Misirlou” is from an unknown location in the Eastern Mediterranean. The lyrics of the song are in Greek, and the first recording was played and sung in July 1927 by Greek musician Theodotos ("Tetos") Demetriades (probably born in 1897, died in New Jersey in 1971). But he was born in Istanbul, Turkey, and there are reasonable arguments in favor of some Turkish origins, or at least Turkish influences, on the song. (Remember, the Ottoman Turks ruled Greece from the 1400s into the 1800s.) In fact the song is considered to be in the rebetiko genre, which combines elements of Greek and Ottoman cultures. Another reason that the song’s origin is usually listed as “unknown” is that several cultures, including Jewish, find the song familiar.

For these reasons, the song is also usually considered to be a folk song with unknown composer(s). But Wikipedia and other sites will tell you that Greek musician Nicholas “Nick” Roubanis copyrighted the song and “credited himself as the composer.” By wording it in this way, they suggest that he learned it as a folk song and dishonestly put his name on it. But the proponents of this theory have not done their homework. There are several reasons to believe that Roubanis might indeed have written “Misirlou”:

—Born in 1880, he was a full generation older than Demetriades or any of the other early recording artists of this song.

—Demetriades moved to the New York/New Jersey area in 1921 and died there in 1971. Roubanis moved to New York City in 1925 (and reportedly taught at Columbia University for a while) and stayed for years before moving back to Greece, where he died in 1968. So it is extremely likely that they had contact with each other in the U.S.A.

—The dates given for Roubanis’s copyright are way too late on every site that I checked. In fact, he copyrighted it back in July 1927, the same month that Demetriades recorded it. That cannot be an accident. Clearly, the copyright and the recording were planned together—more evidence that the two musicians must have known each other. Here is the documentation from the Library of Congress:

Roubanis copyrighted the Greek version in 1934 (probably after being informed that a separate filing was required for it), as you can see here:

—The fact that it seems familiar to musicians of various cultures might be because it uses a distinctive scale found in several cultures, under various names—the same scale discussed in Part 2 of this series. (We’ll use the name “double harmonic scale” in this post.) But the specifics of the song and its lyrics are so detailed and lengthy that there is no reason to assume that it was originally a folk song.

In short, the most likely story is that Roubanis drew upon his Greek heritage, including familiar scales and dance rhythms from Greek and Turkish cultures, to compose an original song. (This is similar to what W.C. Handy did when he collected blues songs and then composed his own. He did not simply write down the songs he collected.) The resulting song is so catchy that one tends to think one has heard it before, even when hearing it for the first time. (This post is already long so I will not go further into the fascinating dance and music elements of “Misirlou.” I have pasted several links into the discussion above.)

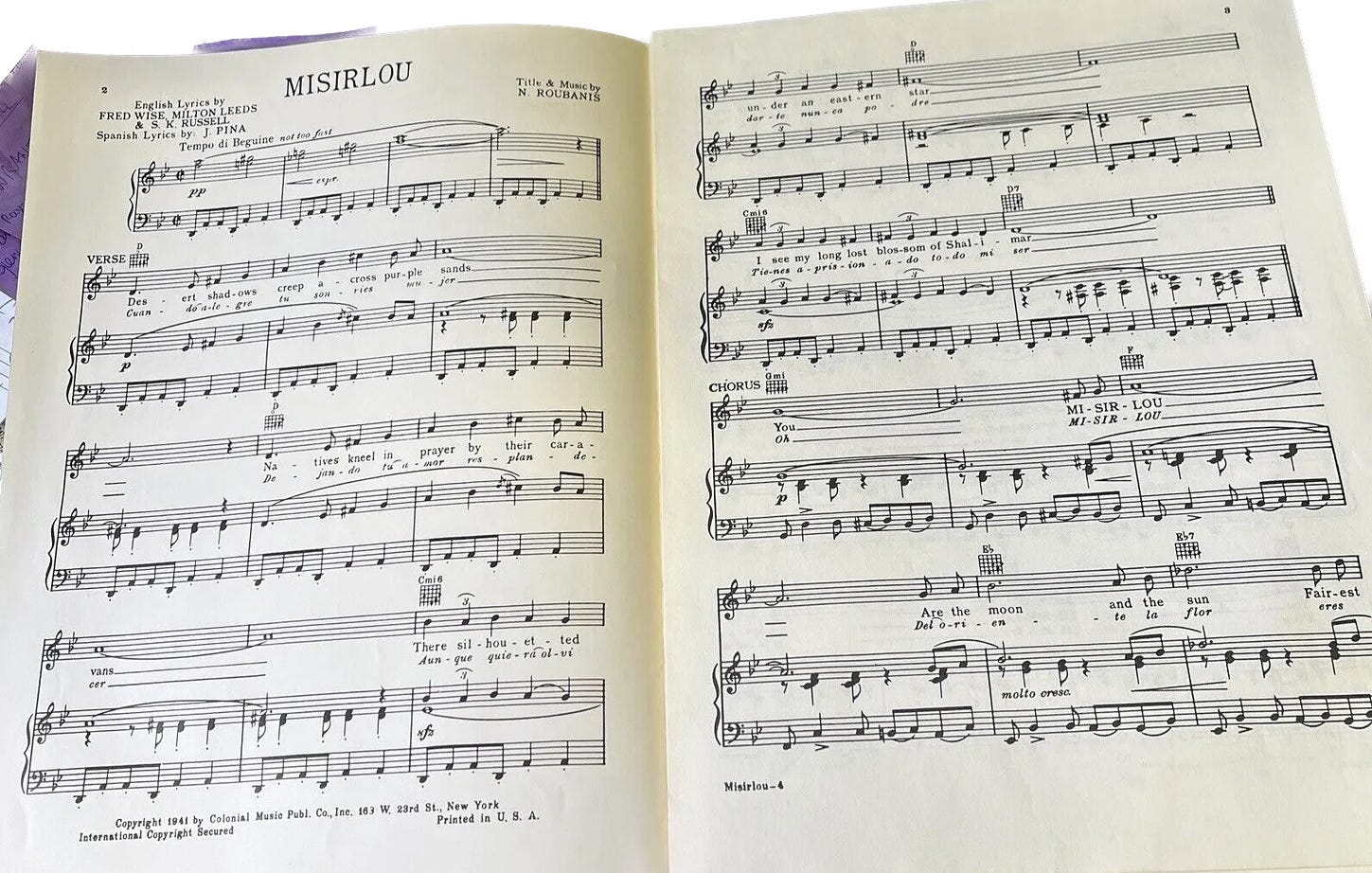

At first “Miserlou” spread among a small circle of musicians, mostly Greeks, by ear. But in 1941, Roubanis created a sheet music version. As I explained in an earlier post, this often involved selling one’s copyright to a publisher, giving them 50% of most royalties. Sure enough, as you can see on the bottom of the first page (these photos are from an Ebay listing), Colonial Music Company now owned the copyright:

Selling the copyright was always a calculated gamble on the part of a song composer like Roubanis. He surely knew that until the song was published, very few musicians would take the trouble to learn it by ear from recordings. Sure enough, the availability of a written version made it much easier for musicians to learn it, and this immediately led to an explosion of recordings, by a much wider variety of musicians. So even though he got 50% of the money, it was much more than “100% of nothing.” To date, it has been recorded many times (reportedly over 600 times) by folk, pop, and jazz artists. It’s such a well-known song that it even gets played at weddings and parties.

Notice that the sheet music is written in D, but with two flats. That makes it a standard phrygian mode, and Roubanis F# and C# where needed to create the so-called Spanish phrygian or double harmonic scale. D is a standard tonal center or drone from Greece through the Middle East and all the way to the raga traditions of India. Most recordings of the piece are in D.

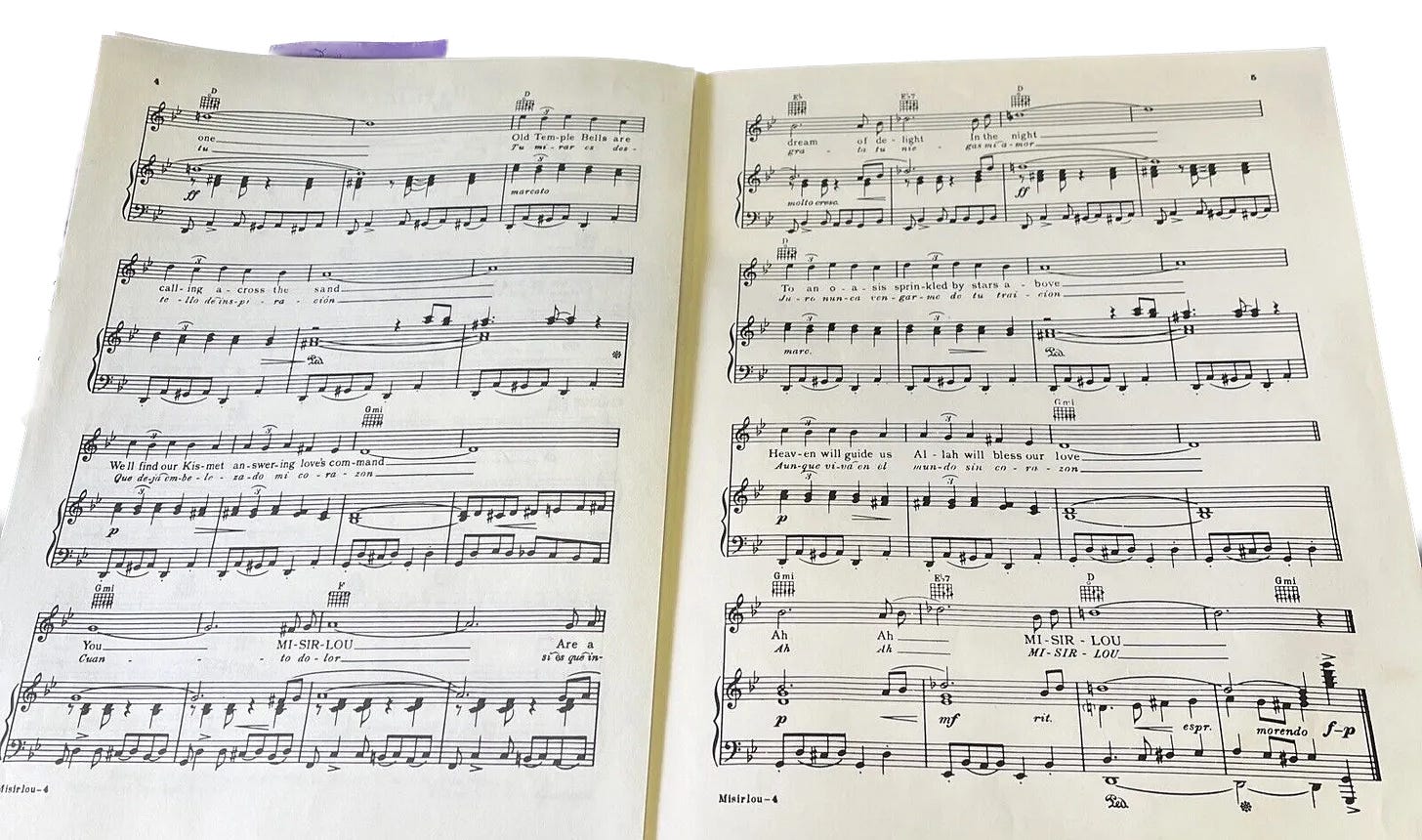

As you can see above, there are two themes, 16 bars each. The first theme—we’ll call it Theme A—goes until the end of the second staff on the second page. It is comprised of four 4-bar phrases: The first phrase starts on D and goes up, to end on A (the fifth). The second phrase of section 1 is the same. The third phrase descends from A (embellished with Bb) to F#; and the fourth descends from A to D. To sum up, the phrasing is up, up, then down in two steps. In many recordings the entire Theme A is repeated, in which case the last chord is D major the first time, but D7, as written, the second time.

The second theme—B— goes up a fourth and revolves around G. It starts with an 8-bar phrase ascending from G to D, but with a G minor chord underneath the D. Then there’s a 4-bar phrase that descends from D (embellished with an Eb) to A; and the last phrase descends from Bb (embellished with C natural) down to D. So again, the phrasing is up, then down in two steps. The entire Theme B is repeated, as written out in the sheet music. (The repeat starts at the bottom of the third page.) Then there’s a 4-bar coda that cadences on Gm—it doesn’t return to the opening tonic of D.

Let’s listen to one of the recordings of “Misirlou” made by Tetos Demetriades. (He recorded it several times.) His arrangement features one instrumental performance of Theme A as an introduction, then vocal renditions of Themes A, A, B, then the first 8 measures of Theme B as an instrumental interlude. Then there’s a dramatic pause, and he comes back to sing a kind of recitation based on the ending of Theme A. Here it is:

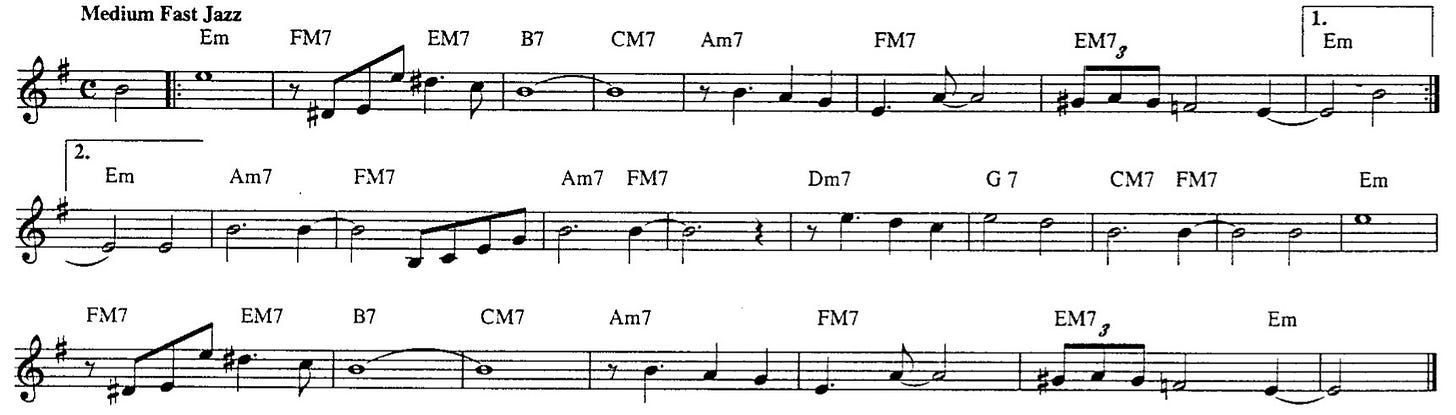

Let’s compare “Misirlou” with a leadsheet of “Nardis” from a fakebook. (Some leadsheets have triplets in measures 3 and 4. Those are from Bill Evans’s arrangement, not part of Miles’s tune. Evans’s chords are different too. You can see them in Part 2, the previous post, linked above.) Here it is—in this one a big M means Major, and a small m means minor:

Miles has constructed a totally original song. His piece, in the key of E instead of D, is in standard Western AABA form, where the A and B sections are 8 measures each. Section A descends from high E to low E, in two steps, resting on the fifth, the note B, in the middle. Section B, the bridge (on the second staff, above), almost entirely embellishes the pitch B.

So the first section of “Nardis” descends in two stages, like the last 8 bars of “Misirlou”’s first section. But in most other ways it is different from “Misirlou.” Miles uses G natural in measure 5, which brings in a bit of the standard phrygian mode. Miles also employs a variety of chords, not only chords that are part of the mode. And the bridge, Section B, does not use the double harmonic scale at all, and emphasizes the fifth note of the scale, not the fourth. However, beneath that melody note is the iv chord (a minor, in the key of e minor), just as Theme B of “Misirlou” uses the iv chord.

So, overall, it may be possible that Miles got the idea to write something using the double harmonic scale, with a descending melody line in the A section and a iv chord at the bridge, from remembering those features of the song “Misirlou.” Remember, 1958 was the year that he became interested in non-Western scales, and in folk music of other lands (see Part 2 again).

And there is good reason to believe that Davis had known “Misirlou” most of his life. The first versions by jazz artists were recorded within a few days of each other in September 1941, and released before the end of that year. One was a vocal version by Woody Herman (included in the bonus for Paying Subscribers below), and the other was an instrumental by trumpeter Harry James. The James version is his own arrangement in D, for an unusual band including a flute and five string players. It has a moderate swing feel, not the traditional rhythm used by Demetriades above. It goes to G at 0:40 for Theme B as expected, but unlike the original, at 1:54 the entire Theme B is repeated up a fourth again, starting on the note C and ending on the note G. After one more Theme B starting on C, it ends with a cadence from G7 to a C minor chord:

Now, if you have seen vintage sheet music, you know that the same song would be issued with different covers, depending on who had made the latest recording of it. Look whose photo is on the cover of this one from late 1941:

I’m leading up to something here, of course. In high school, Miles was a big Harry James fan. Here is what Miles Davis said in later years about James:

“When I was growing up I played like Roy Eldridge, Harry James, Freddie Webster and anyone else I admired” (Downbeat, January 1950). “[On the radio,] sometimes when they had a white band on I would cut if off, unless the musician was Harry James or Bobby Hackett” (Miles’s autobiography p.28). “[In high school, around age 15] we were trying to play all of Harry James’s tunes” (autobiography, p.37). “I just loved the way Harry James played” (autobiography, p.32).

So, wait a second—Miles was born in May 1926, so he was 15 and in high school in the fall of 1941—precisely whan James’s version was released! Under the influence of his teacher, Elwood Buchanan, Miles later left the influence of James behind. But in 1941 he was really listening to James.

And, in case he needed a reminder when he planned to write a new song for Cannonball Adderley in 1958—and he would not need a reminder, really, because most musicians knew “Misirlou” by then—the Philadelphia saxophonist Lynn Hope was performing his own moody, low-key arrangement around 1955. (He recorded it then, but it was not released until 1983.) Hope was well known to Miles and to his band members—John Coltrane, Red Garland and of course “Philly” Joe Jones had all come to him from Philadelphia. And Anthony Barnett of the jazz violin site reminds me that in 1957, Stuff Smith and Dizzy Gillespie released Dizzy’s tune “Rio Pakistan,” which uses the same scale (but they don’t use it in their solos).

As you may know, guitarist Dick Dale recorded the most famous version of “Misirlou” (on the 45 rpm it was originally spelled “Miserlou”). But that was released in 1962, so it’s not part of this story. (But paying subscribers can enjoy four rare 1940s versions, each one very different from the others, at the bottom of this page.)

Bottom Line: “Misirlou” and “Nardis” are two different songs. “Nardis” is not “based on” “Misirlou.” But when Miles became interested in writing songs that used non-Western scales, he very likely remembered “Miserlou,” especially the Harry James version, and decided to write something using the same double harmonic scale, with a descending melody line in the A section and a iv chord at the bridge. That is, “Misirlou” was a likely inspiration for Miles.

I hope you enjoyed this exploration, inspired by Howard Levy’s research. Thank you, Howard, for sending us down this fascinating rabbit hole!

All the best,

Lewis

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Playback with Lewis Porter! to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.